The current theatre of the absurd, with its cast of characters ranging from an unfit President of the United States to his cadre of clownish enablers, distracts us from the truly seismic shifts taking place in America.

Among these shifts are political tribalization, technological upheaval, calamitous climate change, unprecedented demographic shifts, and the persistent and pernicious racism visited upon Blacks.

Long after the current White House occupant is gone, this nation’s federal courts will be making decisions and rendering judgements that will make or break the hopes and aspirations of our current and future generations. And no institution will have more impact than the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS.)

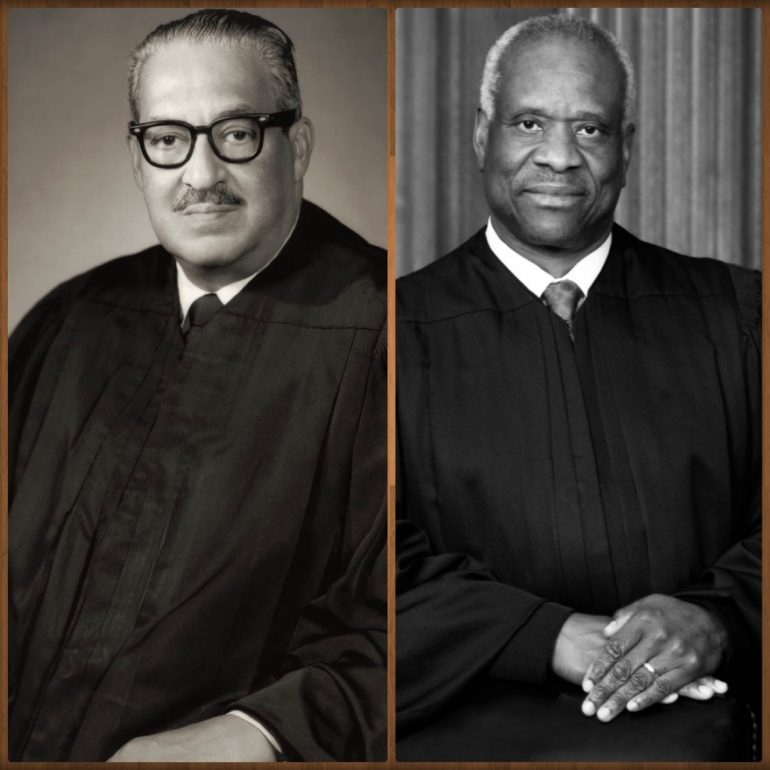

I’m writing here about two Black Supreme Court Justices, both of whom I’ve met and spoken to – one with admiration, the other with bafflement.

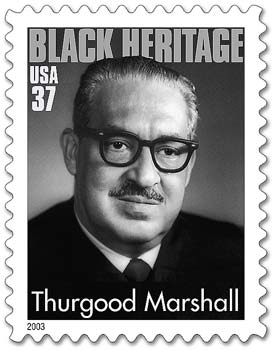

Thurgood Marshall

The first, Thurgood Marshall, brought with him when he joined the High Court in 1967, both the practical experience and sympathetic wisdom gained after founding the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund.

Author Wil Haygood, in his book Showdown: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court Nomination that Changed America (2015), gives an excellent account of how President Lyndon Baines Johnson worked to get the first African-American Supreme Court Justice confirmed by the Senate.

Marshall was a member of my fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha. As an undergraduate, I had the opportunity to meet with him and with Congressman Adam Clayton Powell.

When I blurted out what my University of Chicago education was going to do for me, etc. etc., Powell said, “Don’t tell me how many degrees and diplomas you’ll get; tell me how many pickets have you carried in the heat of the day.”

If memory serves, Marshall joined in the knock-out with: “Damn right. We have to use our education and privilege to the benefit of other Black people.”

Thurgood Marshall made good on this attitude in the Court’s 1978 Bakke case, wherein a white plaintiff challenged the University of California’s consideration of race in admissions to its medical school. It angered Justice Marshall when federal court rulings overturned remedies such as affirmative action.

“Face the fact that there are groups in every community which are daily paying the cost of the history of American injustice,” Haygood quotes Marshall from a 1986 speech. “The argument against affirmative action is…an argument in favor of leaving that cost to lie where it falls.”

Later, in the 1989 J.A. Croson decision, the High Court ruled against Richmond, Virginia’s 30 percent minority business requirement, claiming it did not meet the “strict scrutiny” required by the court on racial matters. Marshall gave a vigorous, cogent dissent.

Clarence Thomas

Upon his death in 1991, Marshall’s seat was filled by Clarence Thomas. No matter how he faltered in his Senate confirmation hearings, I had a hopeful notion that a Black man would adjust when he assumed the position of Justice on the Supreme Court and become a champion for Black people, as was his predecessor.

How wrong I was! My wife Loann said he would never change. Congressman Parren Mitchell even stated, “The man is evil.”

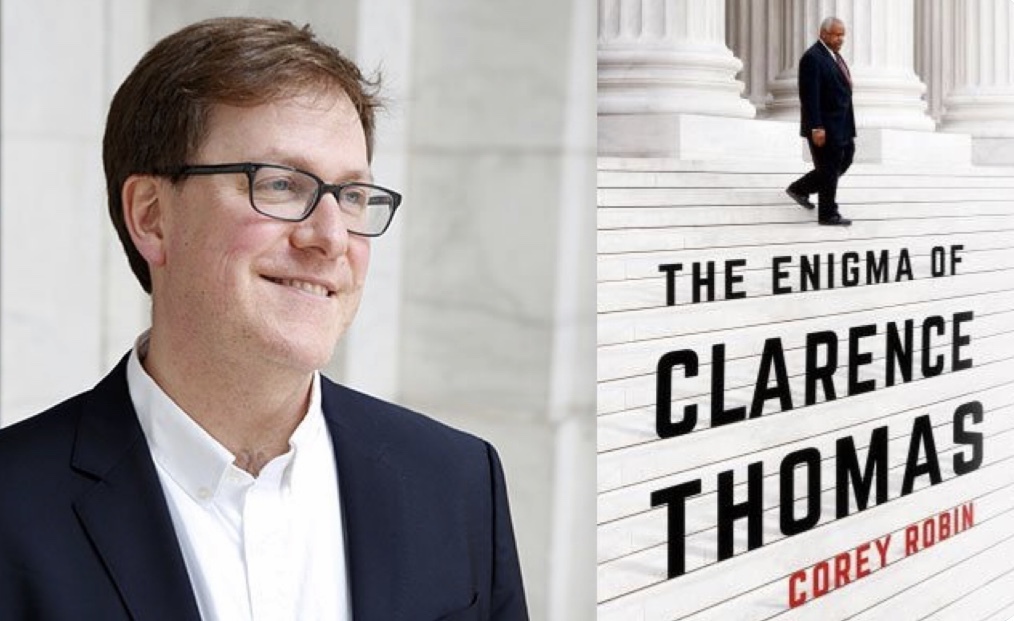

Now comes author Corey Robin with a new book titled The Enigma of Clarence Thomas, which allows us to learn more about this curious, quiet, often silent Justice and how he became that way.

The depth of Robin’s investigative research is admirable, and includes copious notes for those who want to figure out more about this puzzling Thurgood Marshall substitute.

Reviewing this book in the New York Times, Harvard Professor Orlando Patterson writes, “One of the most puzzling and disturbing aspects of popular extremism and racist revanchism is the fact that a Black man – Clarence Thomas, President Trump’s favorite Supreme Court Justice … whose rise from the depths of Jim Crow to one of the highest and most powerful positions in the nation – (could) so relentlessly turn against the Civil Rights Movement and liberal state that made his ascent possible.

“How could a cruelly mocked victim of racism and intra-racial color prejudice come to hold all victims in contempt? Why would someone from the impoverished inner city become the leading defender of the carceral state and American plutocracy?

“How could a Black man who claims to loathe the memory of Jim Crow assail all integration policy and defend states’ rights and racially-targeted gerrymandering, all while living happily with a white wife?”

These are among the very questions I had expected Robin to answer, but he did state that he was writing about a mysterious, puzzling, hard-to-figure-out person.

A Personal Encounter

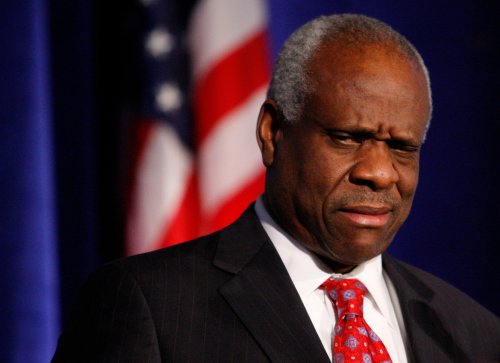

I once met Justice Thomas in Chicago. After his remarks to the Union League Club, there was a Q-and-A session. I asked, loudly, how can you, a beneficiary of Yale University’s affirmative action admissions program, now rule against affirmative action?

Thomas asked if we could speak afterwards, which we did. He told me that he felt affirmative action demeaned Black people. I said, I’m co-founder of a construction business that benefits from affirmative action and am able to hire Black sub-contractors and Black employees. He said “That’s different.” At that point, I saw the uselessness in continuing any conversation.

Yet, perhaps stranger still, as a college student Thomas was a proponent of Malcolm X and considered himself a Black Nationalist.

To that, Robin reports: “Black nationalism is selective. Still, many elements of the program he embraced in the 1960s and ’70s – the celebration of Black self-sufficiency, the scathing attack on integration, the support of racial separatism and Black institutions, the emphasis on Black manhood as the pathway to Black freedom, the reverence for Black self-defense – remain vital parts of his jurisprudence today.”

To my eyes, these virtues must be hiding in plain sight. I don’t see it in his rulings on the High Court. In the 1995, Adarand Constructors case, Thomas voted with the majority in claiming that this case did not meet the strict scrutiny requirement. The loser here was a minority construction contractor.

The most damaging case in which Thomas supported the Court’s conservative majority was 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder. This decision fractured the 1965 Voting Rights Act that addressed racial discrimination in voting in certain parts of the country.

Five years after the Shelby County ruling, nearly 1,000 polling places had been closed throughout the United States, practically all in African-American counties.

Thomas Unchained

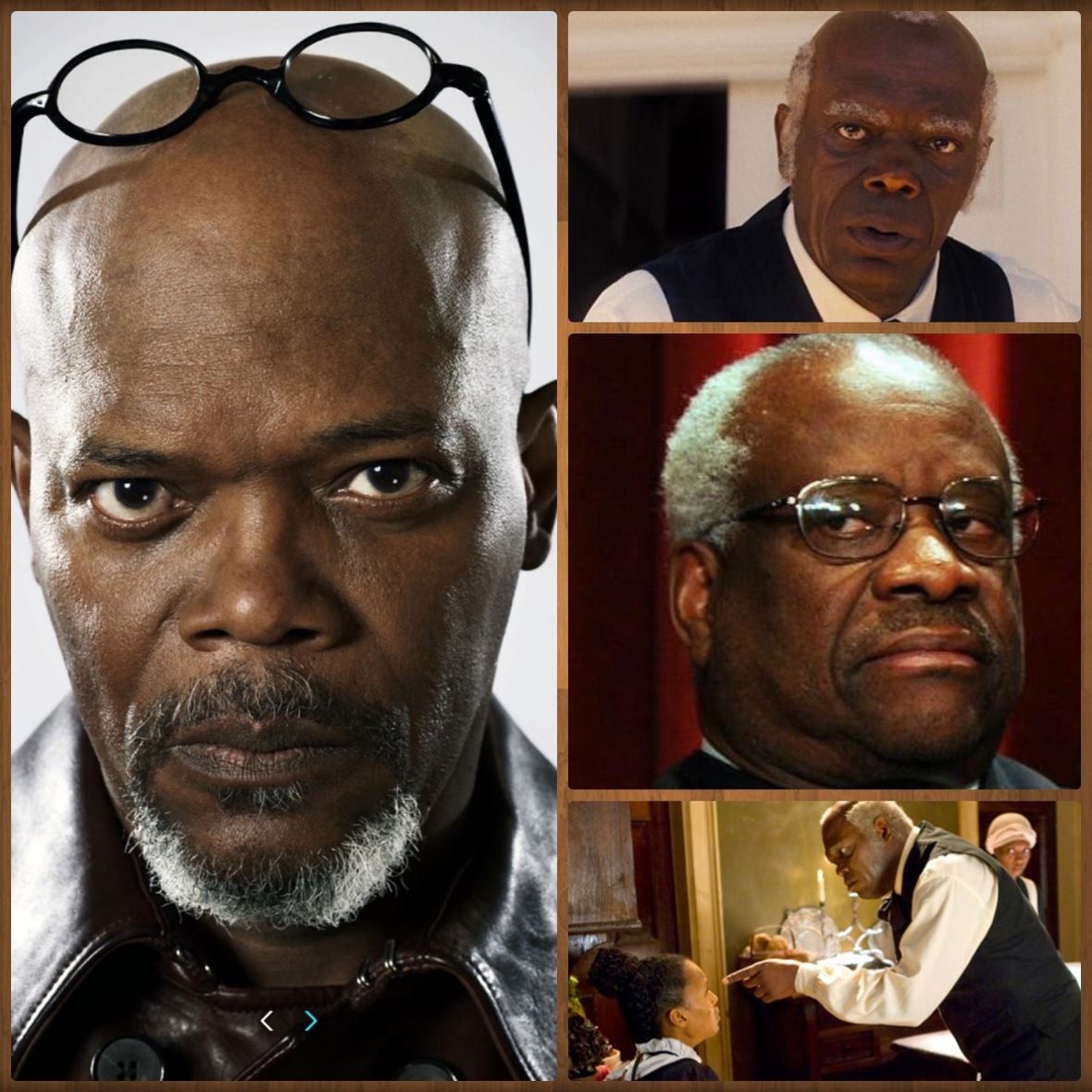

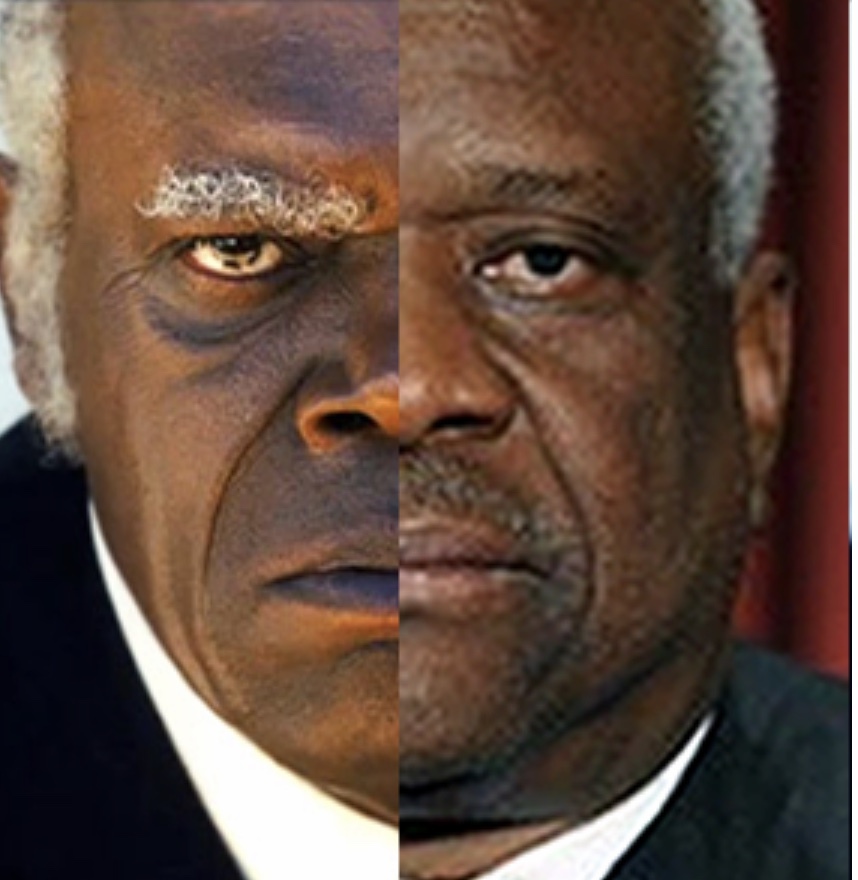

Author Robin’s scholarly research did not answer Professor Patterson’s questions about Clarence Thomas…or mine. Sharing my bafflement with a trusted friend, he referred me to Quentin Tarantino’s movie Django Unchained.

He likened Clarence Thomas to the character in the movie played by Samuel L. Jackson called Stephen. He was what was known as a “House Negro.”

Two years before the Civil War, Django, a slave, finds himself on a mission to capture vicious outlaws. After they accomplish this, his white master, a Mr. Shultz, frees Django. Their travels then take them to a plantation where Django’s long-lost wife is still a slave.

World Press Review called Samuel L. Jackson’s interpretation of Stephen the greatest character of all time. This Uncle Tom is a Black man who will do anything to stay in good standing with the white man, including betraying his own people.

Stephen is a slave on a large plantation in Chickasaw County, Mississippi. The plantation owner leaves operations to Stephen, who pays the bills, calls the shots, and orders the punishment for runaway slaves.

Jackson plays Stephen as a three-faced card: forceful with his underlings; deferential when he’s with his white visitors; a knowledgeable confidant with his white boss.

Stephen is a slave-driving race traitor to some. The first time he sees Django ride up to the door, he becomes rankled as to who this Black man is, riding a horse instead of walking.

The sight of an empowered Black freeman is offensive to his sense of order and position on the plantation. Stephen makes it his business to injure Django, in the interest of protecting his perceived power amongst the slaves.

It gives me no joy and injures my pride to liken the sole Black U.S. Supreme Court Justice to a fictional character who would sell out another Black person in exchange for some perceived favorable position.

The real danger in this parallel is that the Supreme Court will be ruling long after the current White House madness is over.

Justice Thomas will remain as a senior justice and will have tremendous influence, especially given the young age and rightist ideology of recent appointees.

So What’s To Be Done?

For starters, all truth-seeking students, scholars, activists, business organizations, fraternities and sororities need to read the books referenced above and discuss action plans, the most urgent of which is to get out the Black vote in the coming elections.

Recall that only 100,000 votes – combined! – across Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Michigan delivered the 2016 election to Donald Trump.

Voters in safely “blue” states like Illinois, meanwhile, need to organize bus trips next autumn to Milwaukee, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and wherever local African Americans need help tipping the scales toward ending this near-second Civil War mentality and anti-Black hostility.

Conference calls, webinars and all forms of social media need to be used to fight Black voter suppression and get out the vote.

Our people need to be educated on the issues and the local and national Democratic Party campaign coffers need to spend money in the Black community to support these efforts.

Much damage has been done. Yet now – right now! – is the time to begin playing the long game, to begin making sure that the next president, the next Congress, and the nest SCOTUS, begin to right recent wrongs and move this country back onto the path to racial fairness.

(Paul King is a construction consultant and member of Chicago’s Business Leadership Council.)