“Six killed and thirty-one others shot in Chicago’s most violent weekend in 2022,” screamed the Chicago Sun-Times. There were over 622 shootings and 157 murders across the city by mid-April, mainly on the South and West Sides.

There’s no escaping the grim truth: Black people are under siege! Calls for more police and better prevention programs ring throughout African American neighborhoods. Yet while there is broad and loud alarm about dodging bullets and avoiding carjackings, one aspect of this crazy mayhem is little discussed – the impact this is having on Chicago’s health care system.

Think about it. At the end of these shooting episodes, the victim, whether shot by police or by some rival gang, is typically taken to Mount Sinai, Christ Medical, or the University of Chicago Hospital. They are merged into a stream of folks seeking care for everyday illness and injuries – a stream swollen to a flood by the stubborn COVID epidemic.

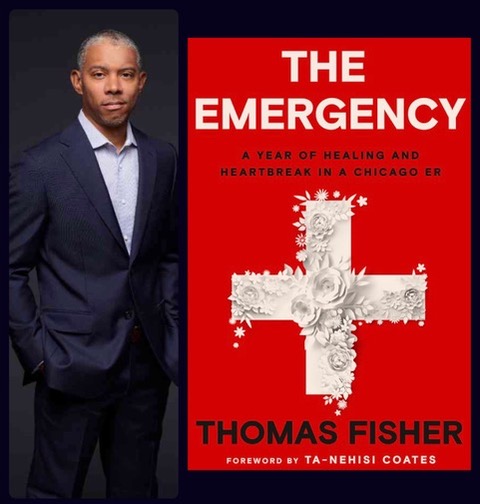

Whether a parent taking a child for vaccination, a senior going for a heart exam or, a good samaritan visiting an inpatient friend, we are all affected by Chicago’s violence and its effect on our health care system. Now comes Thomas Fisher, a veteran emergency room physician, with a new book that shines much-needed light into this tunnel of trauma. It’s titled THE EMERGENCY, A Year of Healing and Heartbreak in a Chicago ER. And it’s nothing short of amazing!

A Little Backstory

But first, a personal backstory. Back in the day, a Shell Oil executive named Joe Moore awarded my construction company a contract to build a service station on South State Street. Years later, he introduced me to his journalist daughter, Natalie Moore, and we stayed in touch. I recently collaborated with Roosevelt University Prof. Erik Gellman to bring author Ta-Nehisi Coates to Chicago. Coates had just published a masterpiece on racial reparations in The Atlantic magazine.

As with Natalie’s keen observations on race (see The South Side by Natalie Moore), Coates provided me with more precise insights into our political and historical situation. I still feel fortunate to know them both. I was amazed when I learned that Coates, Moore, and Dr. Fisher were already friends and collaborators. It turns out that Thomas (T), Natalie(N), and Ta-Nehisi (T) were all Howard University classmates. The talented trio even huddled together at Natalie’s 53rd & Kenwood Avenue apartment to discuss Black issues. So I dubbed these wunderkinder “TNT.”

THE EMERGENCY is one of the essential nonfiction books of 2022. It leaves one gobsmacked, and not just because it describes a year in the life of a big city hospital emergency room during Covid. It also demystifies the maddeningly complex U.S. Health Care System and the subtle but devastating inequities that infect it. Ta-Nehisi Coates contributed to the book Forward: “It was not merely that Tom was an ER doctor directly caring for those afflicted by the plague of gun violence that covered the country and leveled a particular toll on Black neighborhoods. It was that these bodies were rushed into the ER from the streets that Tom called home. He was working not just for the Black community in general but for the same South Side of Chicago where his parents had settled and where he had been raised. He was caring for the lives and bodies of his neighbors.”

The book describes the impact of a capricious system in visceral, bloody detail. Pain and agony are everywhere visible, but looking behind the system’s many curtains through a doctor’s eyes reveals that Black people do not merely live shorter lives than their peers. Instead, their lives are more physically agonizing. And not just the agony of illness and injury, but racism and its consequences, both subtle and overt. “Your body, like many bodies on the South Side, began accumulating injury and illness before your peers on the North Side,” Fisher writes, “And unlike your peers, you had fewer chances to recover and return to your prior health.”

The “you” addressed by Dr. Fisher is a journalistic device that enables the author to write about composite “patients” while guarding their privacy … yet providing plenty of clinical particulars. The author moves from patient to patient doing the best he can, trying to do too much in too little time. He does his best to heal the body – “our most important endowment” – and almost always comes up short. Even as a doctor, he is merely an actor within the system, not the system’s author.

The Burden of Blackness…

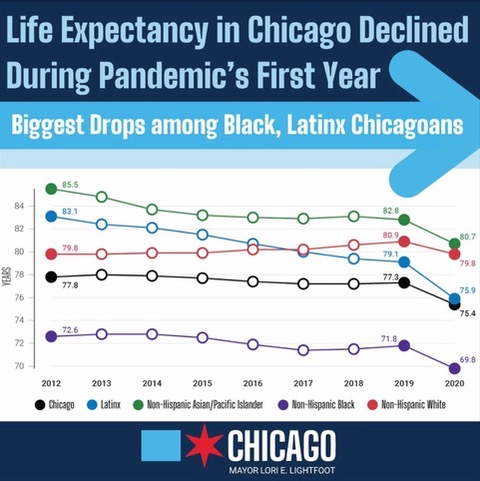

Dr. Fisher is no foreigner trying to apply medical remedies to unknown people. He is of the South Side, using his craft at the University of Chicago mere miles from where he was born and grew up. It is worth remembering the early days of COVID when it was said to be “color blind.” Maybe we wanted to believe that we would find ourselves together on the same footing as mainstream America in a time of crisis, together in our common frailty. But alas, that was never so. Here we are two years later, with Black people having lost nearly three years of life expectancy – roughly triple the loss for whites. We should have known better and should now understand better. THE EMERGENCY helps explain why this is so. Whether it’s the plague of gun violence or the plague of COVID, the burden is never borne equally.

Fisher sometimes takes us outside of the Emergency Room and inside his head. He especially worries about “the worst” happening to him as an ER doctor — getting COVID himself. “How sick would I become?” He laments: “The only certainty (is) that once infected, I would be contagious, and I can’t risk passing the disease along to my family, my patients, to the woman I think I love. So, the terrifying months ahead will be spent mostly alone. It feels like

I will be without human touch during the most stressful time in my life, but the alternative is to infect the people who mean the most to me.”

“Hospital preparations,” he explains, “include a schedule for those who fall ill and alternative housing for folks who couldn’t go home. I prepared my affairs, set an autopsy for my mortgage, stacked my fridge, and withdrew cash as though I’d be gone for six months. So my will is up to date.”

Activism and Advocacy…

Beyond personal concerns, however, Fisher grappled mightily with systemic issues, beginning with the University of Chicago Hospital. He recalls that the hospital’s CEO planned to reorganize the Emergency Department several years ago with ten beds walled off and allocated to Patients of Distinction. (Mainly white patients with insurance.) Eight Beds that had been used as a fast track for ankle sprains coughs, and other minor complaints would be closed. Though “POD” made up less than a fifth of Emergency visits, Fisher realized they would take up almost half of the available space and resources.

“I knew separating patients into separate pods to deliver care was used in emergency medicine, but doing so based on the ability to pay was unheard of. Money became concrete, people became abstract,” . and “I realized how much the plan would segregate the ED racially.” “I decided,” he remembers, that “the day they segregated the ED would be the last day I showed up for a shift.” He relates how it went: “I offered a counter-proposal to reorganize the ED with a basis in illness severity, not insurance status … I was admonished to continue.

“Instead, I was partnering with quiet allies in the administration and organizing the hospital’s young physicians,” he remembered, vowing then that “there could be no compromise that, segregated or otherwise, extracted resources from the poor. Not here, not in the Emergency Room in the heart of the South Side!”

Ultimately, plans to accommodate Patients of Distinction were replaced with a design to structure the space by illness severity. This was a win for Fisher and his group of equity advocates, though some of his allies had had enough. “By the time the smoke cleared a year later,” he remembers, “we had lost a department head and four-section heads. All the emergency medicine faculty under thirty-five departed to restart their careers elsewhere. The CEO, COO, & CFO of the Medical Center disappeared as well.”

The big lesson learned, writes Fisher, was that “health inequity is not simply the product of benign neglect waiting to be fixed but an active and intentional scheme to take from one community and give to another. I witnessed arguments that tried to elevate the importance of morality and science rendered impotent in the face of a financial imperative. The ‘right thing’ was irrelevant. Only power mattered.”

Diagnosis and RX

Realizations such as Fisher’s also occur to those of us who live and operate businesses in Chicago. The intersection of unequal healthcare and sporadic violence doesn’t need a traffic cop. It requires intervention, leadership, and critical thinking.

My company employs over 40 technical staff who oversee the construction of schools, medical facilities, roads, and bridges. These employees deserve protection and informed management oversight. If random shooting is occurring on the South and West Sides, it is incumbent upon Black businesses to become informed and involved.

Toward these ends, I provide the following Action Items for consideration. Notice these include references to mental health. Dr. Gary Slutkin of CeaseFire has long argued that Violence and Mental Health are inextricably linked. Add to this the social and educational disruption brought on by 2+ years of COVID, and new modes of counseling are also needed.

Action Items…

*Chicago is to get $1.9 Billion in Federal COVID Relief. Community Organizations and Health Officials should steer a portion towards reopening city-run mental health clinics in Black areas.

*Research shows too many Black people who have mental illness routinely land in prison. Courts need to order and consider the results of, mental health evaluations prior to sentencing.

*The City should open professionally staffed clinics in minority areas that are free of charge, robustly staffed, and fully accountable for their quality of care.

*Black people don’t get information on prevention soon enough. Ways and means must be found to provide info updates via telephone, online, print, and even in-person home visits.

*The city should offer culturally sensitive programs that require staff to understand and consider the experiences of the Black people they treat. Healing must be holistic while considering the historical and societal contexts in which Black families exist.

*A non-police response network should be created that allows social workers, paramedics, and peers to respond to emergencies, especially points of shootings.

* Support Cure Violence – A World Without Violence Virtual Gala on Thursday, June 2, 2022. Contact: http://cvg.org Dr. Gary Slutkin deserves the support.

*Join and support the Business Leadership Council. This is Chicago’s premier organization advocating for Black Business and is fully engaged in these matters. There is room for startup Black Businesses and mentorship opportunities for members and non-business supporters. Info at https://www.blcchicago.com/

After all, it’s past time to explode racist myths about urban violence. Try some “TNT.”