I understand why people in society use the term “people of color”: it replaces the outdated term “colored people” with one that is more personable and palatable; it allows for a kind of political solidarity between the non-white citizens of the country and the world; it acknowledges the ways in which racism and white supremacy affect people from many groups, not just Black people, and it is a platform for their collective shared experiences, concerns, etc.

That being said, we need to stop saying “people of color” (POC) in instances when we mostly (and sometimes only) mean “Black people.”

What I’m saying is a bit meta, but the public use of the term POC seems to have become less about solidarity and more concerned with lessening the negative connotations and implicit anti-Black reactions – fear, scorn, disdain, apathy – to Blackness.

In popular discourse, POC is often shorthand for “this issue affects Black people most directly and disproportionately, but other non-white people are affected, too, so we need to include them for people to listen and so that people understand we aren’t talking about race as only Black vs. white.”

Saying POC when we mean “Black people” is this concession that there’s a need to describe a marginalized group as “less” Black in order for people – specifically, but not only, white people – to have empathy for whatever issue is being discussed.

When I taught journalism at DePaul University, two of my students wrote in a media critique assignment that we should use “African American” because the term “Black” has negative connotations. Ironically, they wrote those claims even though I, their instructor, had referred to himself as “Black” in class multiple times.

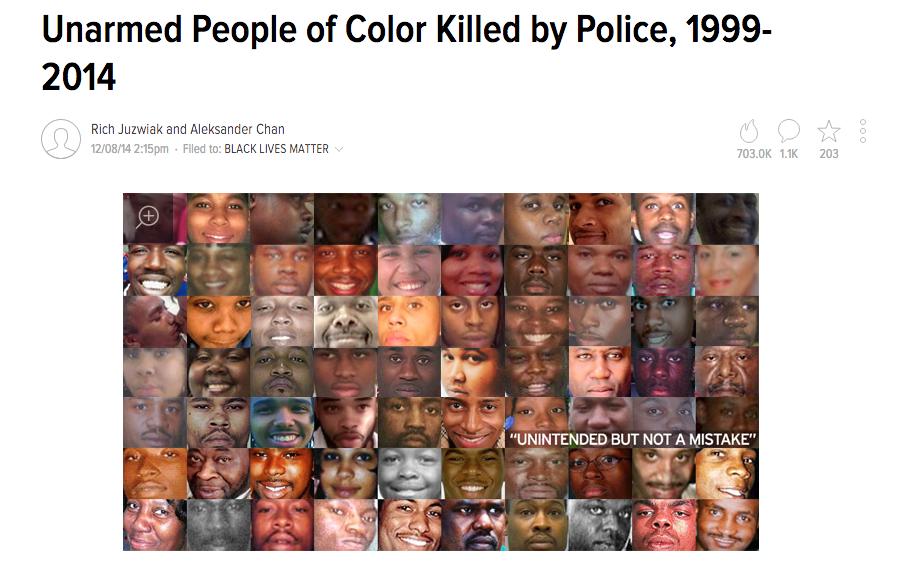

I now teach at Salem State University and in essentially every instance in which one of my students at Salem mentioned something about police brutality in an assignment, I can’t remember any of them not using “people of color” (two students actually used the term “colored people”), even though local or national discussions on police brutality almost always involve Black victims.

To be clear, the use of “person of color” is legitimate and there are plenty of situations where it’s appropriate to use the term. One example is if you are discussing why Hollywood should take greater steps for inclusion and diversity. There it makes perfect sense to use “people of color” to describe the issue.

But if you were raising questions about the lack of Native American representation in films, using them as an example of how Hollywood needs more “people of color” evades the issue.

I’d argue that saying, “We need more Native representation in film” is not only a more direct way to address the problem, but it properly centralizes the specific concerns and issues of the Native American film community, and directs you to the spaces where the solutions can be found – Native communities.

Several racial and ethnic communities, including white people, are negatively affected by the school-to-prison pipeline and police brutality. However, the oppressive systems that spur these phenomena impact the Black community to a much greater degree and, to an extent, were historically designed for that specific outcome.

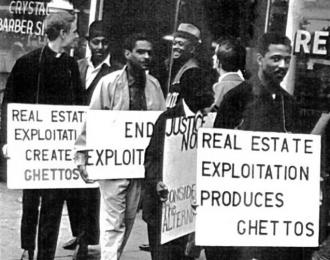

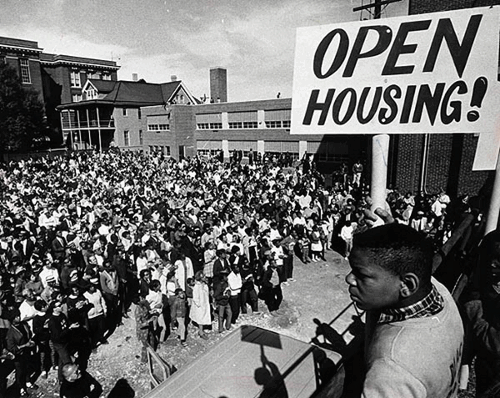

Other groups might face housing discrimination, but the history of redlining in America is a specific response to Black people migrating from the South to northern and western cities.

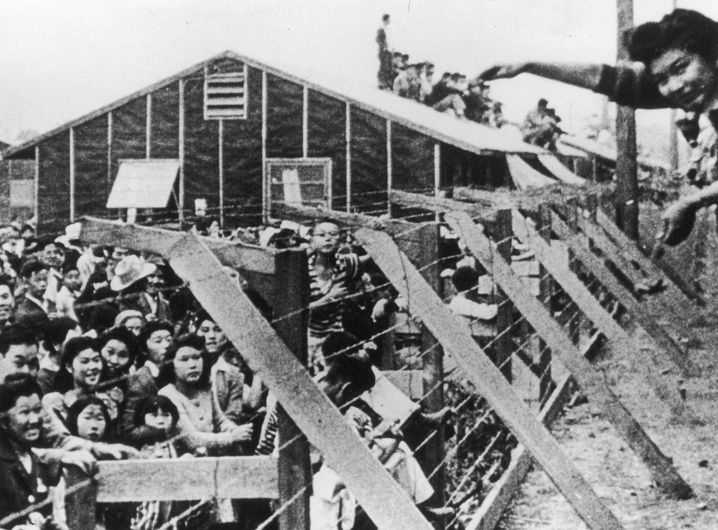

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, Japanese citizens were forced into internment camps. Describing that period as an act of racism against “people of color” erases the extremely specific historical wrongdoing towards Japanese Americans.

When President Trump makes fun of Sen. Elizabeth Warren by calling her “Pocahontas,” that dig is disrespectful to Native people, not “people of color.”

It seems like every week we see a new video of people calling the police on Black people for merely existing in public. Every few weeks there’s another story of a police officer shooting an unarmed Black person because they “feared for their life.”

Yes, other groups face systemic oppression, but while using POC in these contexts isn’t inaccurate, it feels misleading. A “People of Color Lives Matter” movement would be useful, but we can understand why “Black Lives Matter” has a more specific resonance.

For me, “people of color” feels like a hiding place, like I have to hide a crucial part of me in order to not tap into the reactionary fear or apathy towards Blackness. Describing myself as a Person Of Color feels like walking into a space with an apology in hand.

James Baldwin once said, “The plea is simple – look at it.” Words can be mirrors, reflecting the world as it is; or prisms, which have the potential to amplify, but also distort. Our struggle as a society is to find mirrors.

But maybe my simpler plea is for people to know that’s its okay to call me Black. And if you feel it isn’t, I still insist that you do.

(Chicago native Joshua Adams is a writer, arts and culture journalist, and assistant professor at Salem State University. He holds a B.A. in African-American Studies from the University of Virginia and a Journalism M.A. from the University of Southern California.)