At 1:00 p.m. on a Thursday in late May, the courtroom of Associate Judge Lakshmi Jha is about to come to order. The 49-year-old jurist, appointed to the bench less than two months earlier, is beginning her judicial career in expungement court. It is the place where citizens come to have their criminal convictions removed from the public record, and it will be up to Jha, a former Public Defender, to say yes or no.

Few petitioners are in Jha’s courtroom. Most are not required to appear because the State’s Attorney had no objection to their petitions. Others, who had committed serious crimes that the State was unwilling to seal from public view without a hearing, attended by Zoom. Now a matrix of hopeful petitioners, State’s Attorneys, and legal aid lawyers come into view. Some are dressed in suits and ties, some are surrounded by family, others reveal their sterile government offices in the background.

On this day the State’s Attorneys—one exhibiting the long-haired, mustachioed vibe of a hip eighth grade civics teacher, the other of a middle school vice-principal—objected to two petitions. Both of the petitions were from young men who had committed robberies as teenagers. Now, pushing thirty, the men had jobs and families. They’d distanced themselves from their youthful associates. One had even moved downstate, away from the temptations of the big city. They were there to get their convictions expunged or sealed in order to move up in their jobs and to get on with their lives.

Since enactment of the Illinois Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act, which became effective January 1, 2020, any Illinoisan with an arrest or conviction related to cannabis is entitled to free, state-funded legal aid to assist them in petitioning to have all of their convictions sealed or expunged, whether or not the additional convictions are related to cannabis.

The Illinois Equal Justice Foundation administers a cannabis justice fund created by the Act. The funds are distributed to New Leaf Illinois, which is made up of 18 non-profit organizations throughout Illinois that provide free legal representation and information to people who want to remove cannabis convictions from their records.

Once someone is referred, the legal aid provider will look at their non-cannabis charges as well to see if those are eligible for expungement, said Leslie Corbett, Executive Director of the Illinois Equal Justice Foundation.

“Jobs, housing, professional or occupational licensure, business certifications, education, and loans are examples of things that may be an issue if people have records,” said Beth Johnson, New Leaf Illinois’ Program Director.

“If someone saw an attorney 10 years ago, the advice to them would be entirely different than it would be today relating to expungement and sealing,” Johnson said.

It’s a misconception to do nothing about your cannabis record just because cannabis isn’t the biggest conviction on your record,” Johnson said. It’s also a misconception to believe that “everyone’s cool on cannabis” just because it’s legal now.

“Records never go away on their own,” Johnson said. “There are people who can’t believe that a thing that happened when they were 20 years old is blocking them at 47.”

“It’s easy, it’s free,” Corbett said. “And we’ve got organizations standing by ready to help.”

Have a Record? Here’s What to Know…

You may have heard that after passage of the Act, cannabis arrest records were automatically expunged. While that is true for many arrests, whenever there is a court appearance, complete expungement is not automatic. And when there is a conviction, sometimes the criminal record can only be sealed, and not expunged.

The difference between expunging a record and sealing a record is that expungement vacates and erases a record as if it never happened. Sealing a record will hide it from public view, but certain government agencies and employers can still see it.

As of January 2023, over 488,000 cannabis records have been expunged in Cook County, according to the Illinois Cannabis Regulation Oversight Office, CROO.

The Act requires law enforcement agencies to expunge minor cannabis arrest records. It does not apply to court records. A court appearance results in a record in the court system that can only be expunged by petitioning the court. The person must file a petition to get their record expunged from the court clerk’s database, said Brandon Williams, the supervising attorney for the criminal record program at Cabrini Green Legal Aid, a New Leaf grantee. Williams heads the group of attorneys that handles expungement and sealing of any kind of criminal record, cannabis included.

If you are arrested in Illinois, your arrest record can end up in four different databases, Williams said. “Even just being stopped, fingerprinted, and released, you are in the database of the arresting agency, the Illinois State Police, and the FBI. Then, if it goes to court, you have a court record.”

Frequently, when a person is released without being charged, they don’t even know they have an issue until they are denied housing, a job, or insurance coverage, said Jason Robb, senior staff attorney at Cabrini Green Legal Aid. “They thought it was over and then they get arrested for something, or they apply for something, and then then it’s an issue.”

Minor Cannabis….

Minor cannabis arrests–which usually means possession, manufacture, delivery, or intent to deliver under 30 grams–that do not result in court or convictions are automatically expunged and removed from the public record.

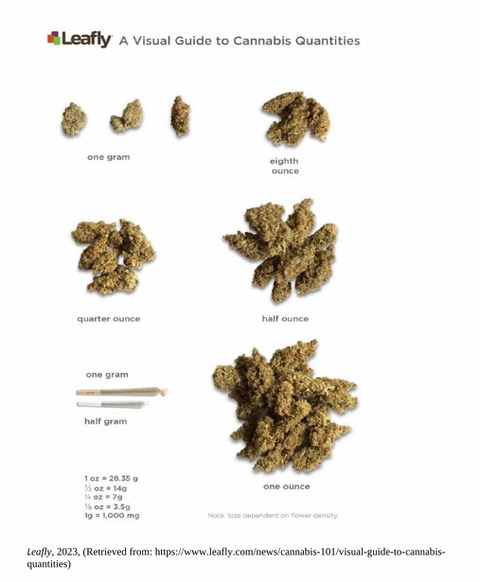

How much marijuana is 30 grams? One gram is about one or two joints. A pre-2020 arrest for possession or sale of 30 times that amount may be eligible for expungement.

According to a staggered schedule set forth in the Act, any Illinois arresting agency or police department in a city or village is required to automatically expunge any records of minor cannabis arrests by 2025.

When there has been a court appearance and no conviction, the individual must petition the court to expunge the record. The expungement will ordinarily be granted without objection, said Cynthia Cornelius, Director of Programs at Cabrini Green Legal Aid. If there has been a conviction, there must be a court hearing on whether the conviction should be expunged or sealed.

“The offense would no longer qualify as minor cannabis if it is associated with a violent crime, even if the violent crime was dismissed,” said Cornelius. But the individual can still file a petition with the court to vacate the criminal conviction.

Once the petition is filed, a 60-day notice period is triggered, which gives the State’s Attorney, the Illinois State Police, the arresting agency, or the chief legal officer for the city or village where the person was arrested, the opportunity to file an objection to the petition, Cornelius said.

Although the Cook County State’s Attorney no longer objects to minor cannabis offenses, the petition is a required procedural step. In Chicago, if there is no objection to a petition, it takes four to six months before that petition is resolved, Cornelius said. The suburban courts take less time.

If no objection is filed, the petition will be placed on a “no objection” court call. The person does not have to appear, and they are not given notice. The judge reads into the record that the petition has been granted and the court’s clerk will send a copy of the order to the petitioner. If there is an objection, a hearing will be held in the case, Cornelius said.

Cook County Automatic Expungement Under 10 Grams

Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx, one of a small wave of progressive prosecutors who took office in 2016, has implemented an expungement program by which her office will expunge, on its own initiative, minor cannabis convictions of 10 grams or less. Foxx recently reported that she has cleared 15,000 such cases. “The individual isn’t involved in this,” Cornelius said. “From their perspective, it is automatic.”

“Felony convictions can follow people long after their time has been served and their debt has been paid,” Foxx said in a statement. “As we work to reform the criminal justice system and develop remedies to systemic barriers, I am proud that justice continues to be served in Cook County, for one, by vacating these low-level cannabis convictions to help move individuals and communities move forward.”

“As prosecutors who implemented these convictions, we must own our role in the harm they have caused—particularly in communities of color—and play out our part in reversing them,” Foxx said.

Pardons by Pritzker…

Minor cannabis convictions may also be pardoned by the governor.

Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker has instituted a pardon process for minor cannabis convictions. In this process, the Illinois State Police provides the Illinois Prisoner Review Board with a list of all minor cannabis convictions on record as of December 31, 2019. The Prisoner Review Board confirms the convictions with the various Illinois State’s Attorneys. If a case fits the clemency criteria, then the Prisoner Review Board submits a recommendation to the governor for a pardon.

The governor issues the pardons and the Attorney General’s Office files petitions to expunge those records. “The petitioner does not have to do anything,” Cornelius said. “The Attorney General handles the petition.”

As of January 2023, Governor Pritzker has pardoned 11,430 conviction records for minor cannabis offenses, CROO reports.

The pardon process is by its nature slow-moving, and a pardon will not vacate a non-minor cannabis or other convictions. Petitioning to have your record expunged or sealed may be faster and more complete.

“If you file to vacate your conviction, you can actually have your conviction vacated and then on top of that expunged, so it’s almost a stronger remedy,” Johnson said.

Non-Minor and Non-Cannabis Convictions…

Once legal aid has an individual’s entire rap sheet, “we can look to see what their convictions are for, what cases can be expunged, and what cases can be sealed,” Williams said.

When the petition is filed, the clerk will schedule a hearing date. The State’s Attorney’s Office has 60 days to object to the petition. If there is an objection, the clerk will set a hearing date.

There are basically three types of objections that State’s Attorney can make, Williams said:

- Drug drop objection: When a person fails to submit a clean drug test within 30 days of filing the petition, the State’s Attorney will object as a matter of law.

- Statutory objection: When the state believes the person is not legally entitled to the relief they seek. For example, filing in the wrong time period or using the wrong form for the petition.

- Public policy objection: When the state believes the person’s record should remain public, outweighing the person’s right to expunge or seal the record.

Williams said The judge will usually decide right after the testimony.

In Judge Jha’s courtroom, the State’s Attorneys made public policy objections based on robberies committed by the two men a dozen or so years ago. As with these petitioners, legal aid can often anticipate objections and prepare a presentation ahead of time.

“For instance, if we were able to get an anger management or a marriage counseling certificate for that petitioner, the state may be inclined to drop their public policy objection,” legal aid attorney Robb said.

Williams said that if the petition is denied, legal aid will review with the client what their following best options are. “The person can essentially refile again anytime they want.”

There are only four types of convictions in Illinois that are ineligible for sealing: criminal sexual assault, domestic battery, DUI, and cruelty to animals, Williams said. All other cases–including murder–are eligible, even after convictions.

The FBI can continue to hold these records in their database because expunging and sealing records falls under state law, Williams said. “It doesn’t usually present a problem for a person because the FBI is not giving the information to anybody else.”

Sealed records in Illinois are only hidden from the public. Williams said that law enforcement and employers authorized to do fingerprint-based background checks–Chicago Public Schools, Chicago Transit Authority, Illinois Department of Public Health–are also authorized to see sealed records.

If you are not eligible to expunge or seal your records, legal aid organizations have programs to obtain alternative forms of relief. Other documents can be used to assist in obtaining employment. One is called a Certificate of Good Conduct. Another one is called a Certificate of Relief of Disabilities, Williams said.

The Certificate of Good Conduct is a statement from the court that states the person has been fully rehabilitated and is no longer deemed to be a threat to the public. “Usually, those work well with the Chicago Public School system and the Chicago Transit Authority,” Williams said.

The Certificate for Relief of Disabilities gives relief where there are certain licenses–such as cosmetology, real estate, and mortuary—that a person cannot hold because of certain convictions. If you have a Certificate of Relief from Disabilities, the state will issue the license, Williams said.

“You have to file a petition to seek those certificates,” Williams said. “Then you have a hearing just like you would in an expungement or sealing hearing to try to get those granted by a judge.”

Taking the First Step…

“Unless people with convictions take that first step, they’re always going to have barriers to employment, housing, or education,” Williams said. “You have attorneys throughout the state willing and able to help you for free to complete this process.”

There is no downside to starting the process now, Robb said. “It can only help you. And the worst thing that the judge can say is just, ‘not today.'”

Lonnie Dawson, 45, said he had 25 cannabis and controlled substance convictions on his record. He learned about New Leaf from someone who had been locked up for 15 years and had turned his life around.

“He owns his own business and his own property right now,” Dawson said.

An auto mechanic, Dawson said he would be accepted for jobs he wanted, then be turned away after the background check. His last conviction was in 1999. For over 20 years, he has worked temporary jobs and was regularly turned away whenever a background check prevented him from being permanently hired.

“I would have a better job. I would have been on the job longer. They would have kept me,” said Dawson, who wishes he had sought expungement earlier. “I’m getting it done now. That’s better than never doing it.”

“It’s a good thing for me because I had a lot of cases on my background,” Dawson said. “I kind of feel free, like it’s a burden off my back.”

“You got to go through the process to get better,” Dawson said.

Meanwhile, in Judge Jha’s virtual courtroom, both petitioners answered yes. After their petitions were granted, the once impulsive teenagers turned family men, each thanked the judge, turned off their screens, and retreated into the future.

Sidebar: If you have any cannabis arrest or conviction, go to newleafillinois.org or call 855-963-9532 to get help or register for free legal assistance.