Over two and a half years ago, in the article “African-American Boys and Men in America Are Killing Themselves and No One Seems to Care,” I wrote about the national disgrace that is the heavier toll of suicide facing African-American boys and men. I said that in minority communities, people often misunderstand what a mental health condition is; therefore, discussing the subject is uncommon. A lack of understanding leads many to believe that a mental health condition is a personal weakness or a form of punishment. African-Americans are also more likely to be exposed to factors that increase the risk of developing a mental health condition, such as discrimination, social isolation, homelessness, and exposure to violence.

What has changed – for better and for worse – since then? Do African-American men and boys continue to have a higher death rate from suicide and violence than others? Is the male suicide rate in the United States still far higher than women? Is suicide still a leading cause of death for minority males? Are African-Americans still more likely to experience serious mental health problems than the general population? Sadly, the answer to all of these questions remains yes.

What has gotten worse? As I’ve said previously, an African-American youth exposed to violence have a 25% higher risk of developing PTSD than non-Black youth. Violent crime rates in US cities have only increased since 2019. This is especially true amongst young African-American men. These two facts seem inextricably tied together: violence leads to PTSD; PTSD leads to violence, over and over again.

Minority access to mental health-related diagnoses and care is impeded by barriers and challenges experienced by minorities who need addiction and recovery support and resources. There also seems to be a strong correlation between mental health issues and overdose rates.

A recent JAMA study suggests that during the COVID epidemic, specifically from January 2019 through mid-2020, opioid overdoses decreased by 24% among whites in Philadelphia. Conversely, opioid overdoses increased amongst Black Philadelphians by over 50%. According to the U. S. Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, only one-third of Black adults diagnosed with mental illness receive treatment. According to the American Psychiatric Association’s “Mental Health Facts for African-Americans” guide, Black adults are less likely to be included in research and receive quality care while more likely to use an emergency room as primary care.

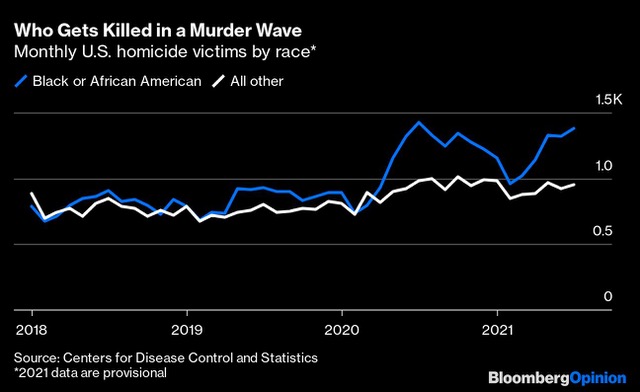

I recently spoke with Dr. Jean Bonhomme, founder of the National Black Men’s Health Network, who relayed some other startling statistics. In 2020, African-Americans made up about 13.5% of the U.S. population, and over 55% of homicide victims, with a more than 65% increase in homicides relative to 2019. Other stark figures that Dr. Bonhomme shared were from a recent CDC study.

In the same period–2019 through 2020–drug overdose death rates for non-Hispanic Black persons increased by 44%, while for non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) persons, the drug overdose death rates increased by 39%. Other numbers that jump out include the 2020 death rate from overdose among Black males aged 65 years (52.6 per 100,000) as being nearly seven times that of non-Hispanic white males of a similar age. Meanwhile, treatment for substance use was at the lowest for Black persons (at 8.3%).

Data from the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors shows one factor in the mental health crisis disproportionally facing the Black community. This data indicates that the number people admitted to psychiatric hospitals (and other residential facilities) in the US declined from 471,000 in 1970 to 170,000 in 2014. This reduction in the availability of a potential intervention opportunity appears to have led to growth in incarceration and similar non-therapeutic interventions, which, in the absence of these other options, take the place of real psychiatric help.

We must also consider that the life circumstances of young Black men must also be the driver of many of these differences and disparities. Out of decency alone, the US needs to find a way to identify and target systemic changes to benefit these populations, which have the most urgent need.

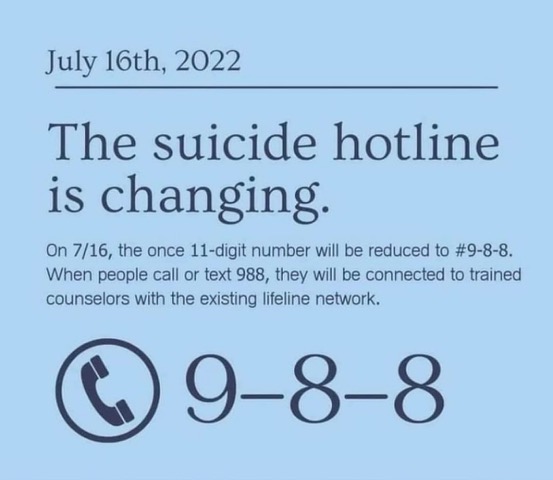

Are there any positives the can impact minority mental health? Absolutely! The new nation-wide 988 crisis number launch went live July 16th of this year, and text-based services will be included. Studies suggest that over 75% of those using text on existing crisis services are under 25. Minority populations in the USA have a higher percentage of young people in younger age groups than whites. Therefore, better serving an underserved community is an outcome that is a clear improvement on the current situation.

Men’s Health Network redoubles its recommendation that those charged with the health and social welfare of boys and men consider the following:

1. Acknowledge the heterogeneity of boys and men and the unique needs of diverse populations

2. Develop culturally appropriate male-focused screening tools

3. Develop guidelines that recognize the need to regularly and routinely screen boys and men for both physical and mental health issues

4. Address the poor reimbursement for behavioral health clinical services

5. Establish culturally and gender-appropriate programs to identify, interrupt, and manage mental health issues in African-American boys and men, providing education and training for those in the community who interact with boys and men.

With this said, Men’s Health Network, Healthy Men, Inc., the National Black Men’s Health Network, and the Men’s Health Caucus have launched a public awareness campaign, “You Ok, Bro?” (https://www.youokbro.org/) and will be hosting a workshop summit on Thursday, October 13th, 2022 at the National Press Club in Washington, DC to build awareness of the mental health crisis now erupting in the male population of the US. This important event will be live-streamed. The summit aims to examine and return recommendations to help reverse the recent increase in mental health crises. Behavioral experts from multiple organizations will share research, trends, and discoveries and supply information to men, boys, and their loved ones to help them identify the signs of mental distress and recommend ways to improve mental and emotional fitness.

“You OK, Bro?” is the beginning of a dialog that can start with those words, whether between just two men, or at a national scale. We hope it changes the way the US sees and talks about men’s mental health.

Men’s Health Network (MHN) is a national non-profit organization whose mission is to reach men, boys, and their families where they live, work, play, and pray with health awareness and disease prevention messages and tools, screening programs, educational materials, advocacy opportunities, and patient navigation.

Men’s Health Network (MHN) is a national non-profit organization whose mission is to reach men, boys, and their families where they live, work, play, and pray with health awareness and disease prevention messages and tools, screening programs, educational materials, advocacy opportunities, and patient navigation.