Deborah D. Douglas is an award-winning journalist, cultural critic, and thought leader specializing in the African American lived experience.

Deborah lives in Chicago, where she was born, but is a self-described product of the Great Migration: She started school in post-uprising Detroit and came of age in metro Memphis. After graduating from Northwestern University, she traveled the country as a reporter, landing in Jackson, Mississippi. She’s taught best practices to journalists in Karachi, Pakistan, taught in South Africa twice, studied HIV and malaria prevention in Tanzania, and traveled to Kenya, Tunisia, and Senegal, and throughout Europe. She is currently the Eugene S. Pulliam Distinguished Visiting Professor at DePauw University, creating courses to show student-journalists how to center marginalized voices in their work.

Deborah has served as the managing editor of MLK50: Justice Through Journalism, a reporting project examining the economic realities of Memphis, Tennessee, 50+ years since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated there. Previously, she was the No. 2 at the Chicago Sun-Times editorial page and a columnist. She is a senior leader at The OpEd Project, leading fellowships and programs that include the University of Texas at Austin, Dartmouth College, Columbia University, Urgent Action Fund in South Africa and Kenya, and the McCormick Foundation-funded Youth Narrating Our World (YNOW).

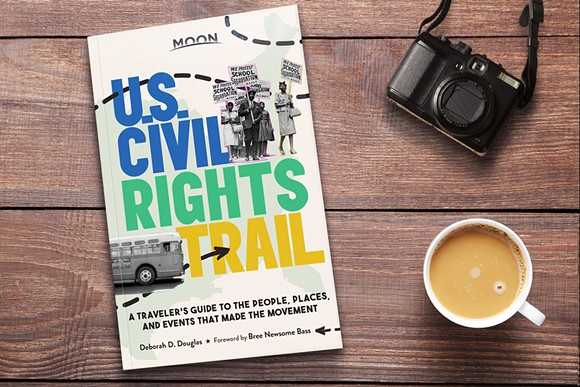

While teaching at her alma mater, Northwestern University’s Medill School, she created a graduate investigative journalism capstone on the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and taught best practices in Karachi, Pakistan. An award-winning journalist, 2019 Studs Terkel awardee and founding managing editor of MLK50: Justice Through Journalism, Douglas is the author of “Moon U.S. Civil Rights Trail: A Traveler’s Guide to the People, Places, and Events That Made the Movement.” She is among 90 contributors to the New York Times bestselling “Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019,” edited by Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain (Random House). Deborah has won numerous awards for her writing for Oprah magazine and other outlets.

In her career, she’s had the honor of speaking with civil rights icons, including Rev. Jesse Jackson, Rev. James Lawson, Diane Nash, Bernard Lafayette, Bree Newsome, Rev. Bernice King, and Rev. Martin King III.

N’DIGO sat down with Deborah D. Douglas and discussed why she decided to write such an interesting book.

Moon U.S. Civil Rights Trail: A Traveler’s Guide to the People, Places, and Events That Made the Movement by Deborah D. Douglas

N’DIGO: Why did you write the book on the U.S. Civil Rights Trail?

Deborah D. Douglas: A group of travel offices designated an official “civil rights trail.” Initially, it was southern but then it extended. It extends from Wilmington Delaware to Kansas to the West and it goes into Florida and Louisiana. This is the story of the south.

Why is the book important?

Civil Rights history is American history. We are literacy surrounded by greatness and don’t even know it. So many of the places I visited in writing this book are part of the daily fabric of our lives but we miss opportunities to engage with them from viewpoint of greatness they represent, Thankfully, our cities and institutions are walking up to the narrative power of African American history, including the Civil Rights Movement. This story happens to be relevant on so many levels right now and urgently so. If you don’t know your history you promise to repeat it, that’s where we are now as we see new laws on voter rights. Many of the issues that were pertinent for the civil rights movement we continue to wrestle with today. They are just as important today as they were in the Civil Rights movement, mid-century.

What are some of the highlights of the book?

I didn’t travel the entire trail. I created a narrative. I went to Atlanta for many reasons, it is the home of Dr. King, where he lived and worked. I went to Memphis because the Labor Movement was important and it is where Dr. King died. I went to the Mississippi Delta because Emmitt Till was murdered there and of course that incident stimulated the modern-day civil rights movement.

I went to Nashville because this is where Rev. James Lawson and other train people for nonviolent direct action. Nashville was the first city in the south to begin the process of desegregated public accommodations. Diana Nash, CT Vivian, John Lewis, James Bevel, and Bernard Lafayette, came out of this group. I went to Greensboro because of the sit-in movement. There is an important museum there, The International Civil Rights Center and Museum, that people should tour. It is the former Woolworth’s building that the Greensboro four engaged the sit it.

What did you learn that you didn’t know?

The day the four girls were bombed in the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham on that day, six children were murdered not four. The other two were Black boys in another situation. This speaks to the level of danger that these people in Birmingham faced daily. The boys were Virgil Ware, 13 years old, and Johnny Robinson who was 16 years old. These were racialized murders and the kids were killed on the same day.

Name the best 3 restaurants you discovered on the trail.

I prioritize Black-owned businesses; I wrote about Black businesses. The top restaurants were. Lassis Inn Restaurant, in Little Rock Arkansas. They had something called “buffalo ribs” that is actually a fish, cut like barbecue ribs. Daisy Bates, from the Civil Rights Movement, ate there a lot.

Chef Tam’s Underground Café, in Memphis, Tennessee, had the best of everything, especially the deconstructed peach cobbler. The chef is Tamra Patterson she cooks like she likes to eat.

What did you learn about the south as a Chicagoan that you didn’t know?

I am a great migration baby. I was born in Chicago’s Austin community and my father ran a business, Howard’s Auto Body Shop on Madison. My parents divorced and my mom moved to Detroit and I started school in Detroit, and I completed high school there. I was a ping pong child, moving back and forth with my grandmother who lived in a small town outside of Memphis, where my mother was raised. I went to my mother’s church and her school. My mother’s third-grade teacher was my librarian. The librarian was Vernon Jarrett’s cousin and she lived with the Jarrett family when she went to high school because there was no school for her to attend where she lived. She said she became radicalized because she was reading Vernon Jarrett books by Black authors and in turn, she is the person who helped me to develop my sense of Black consciousness.

What do you want people to get from your book?

I want them to fill in the blanks on what they don’t know about the civil rights movement and I want them to locate themselves in the story. I want us to begin to value our cultural narrative, we have history right outside of our front door.

How does your book relate to Chicago?

I am excited about the development of the house museums in Chicago, like the Emmitt Till Pilgrimage site and the Lu Palmer mansion because we need to better harness our cultural narrative to understand ourselves, social policy, and wealth creation.

In Nashville on the stairs of the public library, there is signage on the stairs that says “History Informs the Future.” How do you relate to that?

It is the perfect statement for this book.

What did you see that is most memorable?

All things associated with Emmitt Till, like the Tallahassee Courthouse, where the trial was held and I sat in the judge’s chair. It is still a working courthouse.