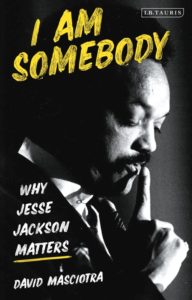

David Masciotra is an author, public lecturer, political commentator and cultural critic. He is the author of Mellencamp: American Troubadour and Working On a Dream: The Progressive Political Vision of Bruce Springsteen. His new book is I Am Somebody: Why Jesse Jackson Matters published by Bloomsbury Publishers.

He documents Jackson’s work as a “political figure” and how he modernized the Democratic party with his historic presidential candidacy, making way for Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton’s run. He broke the ceiling and changed the party, indeed and he registered more people to vote than any other in American history. He addresses Jackson’s international rescue missions and how he simplified negotiations for the release of American captives with a religious moral appeal.

Masciotra captures the brilliance and history of Jackson’s ministry, that is so often confused. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. challenged America’s constitution, whereas Jackson challenged America’s caste system. David’s book is an insightful read on the dynamics of Jackson and the success he brings to the political process without ever holding political office, but being responsible for many who do over the past 50 years. Change.

Masciotra is a cultural columnist with Salon, and has also written about cultural issues and the arts for the _Daily Beast, _The Atlantic_, the Washington Post, Blurt, _the Los Angeles Review of Books, and politics for AlterNet, the _Indianapolis Star, and Truthout. He has written about life and literature for The Cresset. He is a former columnist with PopMatters.

N’DIGO sat down with David and discussed his new book I Am Somebody: Why Jesse Jackson Matters.

N’DIGO: What made you want to write the book, I Am Somebody: Why Jesse Jackson Matters?

David Mascriotra: Growing up in the Chicagoland area, Jesse Jackson Sr., and his son, Jesse Jackson Jr., were fixtures of our sociopolitical environment. My mother purchased a biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. for me when I was in the third grade, and when I expressed bafflement and heartbreak over King’s assassination, she attempted to ease my outrage by reading aloud the closing passage about how King’s work continues in various forms, one of which was the advocacy and activism of Jesse Jackson in Chicago. Simultaneously, my grandfather found Jackson’s work on behalf of labor unions admirable, and would regularly announce at our breakfast table, “Jesse’s helping workers again.”

Many years later when I studied political science at the University of St. Francis, I found Jackson’s presidential campaigns of the 1980s singularly inspiring for their advancement of cross-cultural progressive politics.

Many years later when I studied political science at the University of St. Francis, I found Jackson’s presidential campaigns of the 1980s singularly inspiring for their advancement of cross-cultural progressive politics.

In 2014, I was able to meet with Jackson to interview him on the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of his first presidential campaign, and wrote about it for the Daily Beast. It is one of the great honors and pleasures of my life that Rev. Jackson and I developed a rapport. One interview turned to several, and soon we were in regular dialogue. I’ve had an ongoing conversation with Rev. Jackson for six years now, and it is the best conversation I’ve had. The depth and breadth of his work, along with the brilliance of his analysis, quickly made it clear that one article, or even a series of articles, would prove insufficient to capture the importance and influence of his work, and the power and drama of his story.

You have written a definitive book on Jackson’s career as a political figure, describe what you observe of Jackson as a “politician.”

Thank you so much for that flattering assessment. Jackson is certainly an unconventional politician, primarily because he did develop out of the elite sectors of the American duopoly, or have access to any corporate networks of support and funding. One of the words that many Americans, including those in the press, appear not to understand is “populist.” Jackson captures authentic populism in that his presidential campaigns reacted to the people’s needs and desires, and that he steadily gathered momentum and political credibility as an organizer – working directly with the poor and working class, fighting for racial equality for Black citizens, economic justice for labor.

Delmarie Cobb, his former press secretary who I interviewed for “I Am Somebody,” calls Jackson’s political program the “politics of usefulness.” He takes politics from the pathos to the pavement in order to demonstrate how public policy, political organization, and democratic representation can actually enhance the quality of life for average people.

Because of the horrific history of Jim Crow, and the persistence of racism in American life, Jackson’s project begins with freedom, justice, and equality for Blacks, but it extends to everyone in the location of common interest. He captured it well in his 1984 slogan, “Let’s leave the racial battleground, find economic common ground, and reach for moral higher ground.”

That is the essence of participatory democracy. One can read its story in the work of historian Howard Zinn, and the analysis of W.E.B. Dubois, just as one can also find it in the leadership of Eugene Debs, Martin Luther King, and Cesar Chavez. Jackson is among them as one of the most effective and consequential dissident figures of American history. He is also, as you know, an international figure – leading the fight for the emancipation of Nelson Mandela, making religious freedom possible in Cuba, and rescuing hostages in many countries, including Syria and Iraq.

How would you describe what you label as “The Jackson Factor?”

It actually isn’t my label, but the affixation of Mary Matalin, a right wing political operator who worked for the Republican candidates throughout the 1990s. She meant it as a pejorative against Jackson, but I flip it, and use it as a compliment.

The background is that Bill Clinton publicly betrayed Jackson at the Rainbow/PUSH convention in 1992, bashing Jackson for allowing Sister Souljah – a rapper who had just made hateful remarks related to the LA Riots – to speak at the convention. The circumstances surrounding this event are complicated, and readers can learn the entire story in the book. In short, Clinton seized upon the moment to show white voters that he was not beholden to Jackson. Matalin commented that Clinton’s move was clever, because it allowed him to “deal with the Jesse Jackson factor.”

Similarly, in 2008, mediocre writers speculated in 2008 how Barack Obama would distance himself from Jesse Jackson.

This leads me to ask, what does it say about our political culture that there is pressure on Democratic candidates for president to show that they are not too cooperative with the country’s leading civil rights leader?

My conclusion is that the “Jesse Jackson factor” places ethics over expediency, the rights and health of the poor over corporate profits, and universal justice over narrow party interest. Needless to say, this makes many people, most significantly the corporate donors and party leaders who court them, uncomfortable.

What Mary Matalin meant as disparagement against an outspoken leader that the major parties could not control, I use as a term to explore how political elites deal with a true tribune of the people.

You write that probably the worst thing that could happened to a corporate executive would be to get a call from Jackson. What does that mean?

That warning comes from one of the premier public relations specialists in the industry when assessing Jackson’s crusades against racism in corporate America. Many Americans have subscribed to the American myths of meritocracy and racial fairness in Northern states. Beginning with Operation Breadbasket in the 1960s, then in the early years of Operation PUSH, and all the way to the present, Jackson has acted as a human battering ram against the racist barriers of American economic structures. The early years of Breadbasket alone, according to many journalists and historians, resulted in thousands of jobs for Black workers, admission in trade unions for thousands of Black workers, and the procurement of tens of millions of dollars in benefits for Black business owners through product placement, product promotion, and government contracts.

The economic institutions and big businesses of the United States, along with the major unions, and the big banks were so viciously racist that even the most talented and qualified Black professionals and entrepreneurs were often shut out of opportunities that lesser whites took for granted. Through exercising the boycott, and sophisticated means of political pressure, Jackson and his organization remade and reshaped American economic institutions, largely creating “Black economics” is the process.

The warning to corporate executives is that if they get the call from Jackson, they should know that their racism will no longer remain unchecked and unpunished. Jackson is not looking merely to penalize bigots, though. He’s trying to alter institutions, and create opportunities. For example, out of protests against Toyota over a few racist advertisement campaigns they ran, Jackson negotiated for the investment of dealerships in Black neighborhoods, the recruitment and training of Black managers, and a multimillion dollar scholarship campaign for Black students that continues to the present.

What three things do you think are most significant of Jackson’s career?

This is an interesting question, and obviously a highly subjective answer, but I would argue that most significant are Jackson’s years with Dr. King, because of the moral grandeur and political importance of King’s leadership, and also the extent to which King’s philosophy influenced Jackson, his presidential campaigns in 1980s, because they reinvented the Democratic Party, and his international work. On the latter, he is a world leader for human rights, rescuing hostages far and wide, and helping to win religious liberty in Cuba.

Is there anything you left out of the book intentionally?

There were a few stories that Jackson told me “off the record” relating to his personal relationships with certain historical figures. As fascinating as these stories were, I take journalistic ethics seriously, and therefore would not violate my promise to Rev. Jackson.

The biggest challenge of writing “I Am Somebody” was curation. Because of the immense amount of accomplishments in Jackson’s career, the book could total 1,000 pages. The publisher and I agreed that the book should be accessible to people not as familiar with Jackson’s career. Therefore, we kept the length under control.

How long did it take you to write the book?

The book is the product of six years interviewing Rev. Jackson, and observing his work up close. I also interviewed many other key figures, including Rev. Sharpton. The actual writing, however, took one year.

What do you hope your book achieves?

I hope that “I Am Somebody” not only captures the drama, urgency, and achievement of one momentous life, but also serves as a predicate for understanding and analyzing dissent, progressive politics, civil rights activism, antiwar activism, and economic justice.

To study the life of Rev. Jesse Jackson is to also gain insight into the American structures of injustice he fights, and the methods likeliest to succeed in changing them. Similar to how one cannot study Vaclav Havel without learning about the Iron Curtain and Soviet communism, or study Nelson Mandela, without learning about South African Apartheid, one cannot study Jesse Jackson without learning about systemic racism, how corporate capitalism exploits people, and the horrific costs of war.

How would you categorize your book?

It is a work of fusion, combining elements of biography, elements of political analysis, elements of history, and elements of journalism.

Is it interesting that the men who have made the greatest social changes in America have been outside of the system? How would you account for that, from King to Jackson?

One of the most profound and important statements Jackson makes in my book is that the ruling class wants “enough democracy to legitimize their power, but not enough for people to challenge their power.” Despite what we learn in school, the United States never had an authentic democracy. Most of us are aware that at the country’s inception, the founders massacred the indigenous population and disenfranchised the survivors, enslaved Blacks, subjugated women, and even denied poor white men the right to vote.

The system serves the powerful, and that continues right up to the present. As I write, we are only two days away from the presidential election. The Democratic candidate – Joe Biden – undoubtedly has more popular support than Trump. So, why are Democrats even worried about the outcome? Two reasons: The Electoral College and voter suppression.

An interesting contradiction is that there are “hidden Easter eggs,” to use the words of political scientist Christina Greer, who endorsed “I Am Somebody,” for citizens like her – she is a Black woman – to discover and use in the Constitution for the expansion of their own rights, freedom, and legal protection. Even Greer’s tactic, however, is in defiance against the system. In almost a postmodern sense, it uses what is within the system against the system.

The story of progress in the United States, as captured by the civil rights movement, the women’s rights movement, the gay rights movement, the labor movement, the American Indian Movement, and the environmental movement, is the story of beleaguered and neglected people coalescing in the advancement of their own humanity against legal and state-sanctioned oppression. Jackson, King, and others led these movements out of necessity. The only way to move the system was to bring sufficient pressure to bear on those within it.

“I Am Somebody: Why Jesse Jackson Matters” offers a study of one immensely consequential dissident leader, but I also hope, a manual for other activists and organizers to learn from Jackson’s wisdom and techniques so that they may continue the struggle for peace and justice in their own neighborhoods, and according to their own experiences.

Masciotra lives in Indiana, and teaches literature and political science courses at the University of St. Francis and Indiana University Northwest. He is available for speaking dates and can be reached at DavidMasciotraWriter@gmail.com