By most accounts Michael Kutza has worked a dream job. Who in their right mind wouldn’t want to spend their days binge-watching movies in exotic places around the world while also hobnobbing with some of the film industry’s most famous, from Loren to Minelli to Preminger and Spielberg?

Watching films served amply as a babysitter to Kutza at age six while his parents, both doctors, worked their respective jobs: “Dad was in surgery early in the morning; Mother was delivering babies,” he recalls.

As a child Kutza was so smitten by the movies that later when it came time for him to get a job, he bucked the family tradition of becoming a doctor and opted instead to create the Chicago International Film Festival (CIFF) in 1964 with a little help from silent-film star Colleen Moore. There was never a Plan B if the festival didn’t work out.

“I was too obsessed. It had to work out,” Kutza admits. “That’s the tough part of leaving it, you know?” Nevertheless, after 54 years of running the festival, he says it’s time “to move on to my next adventure.”

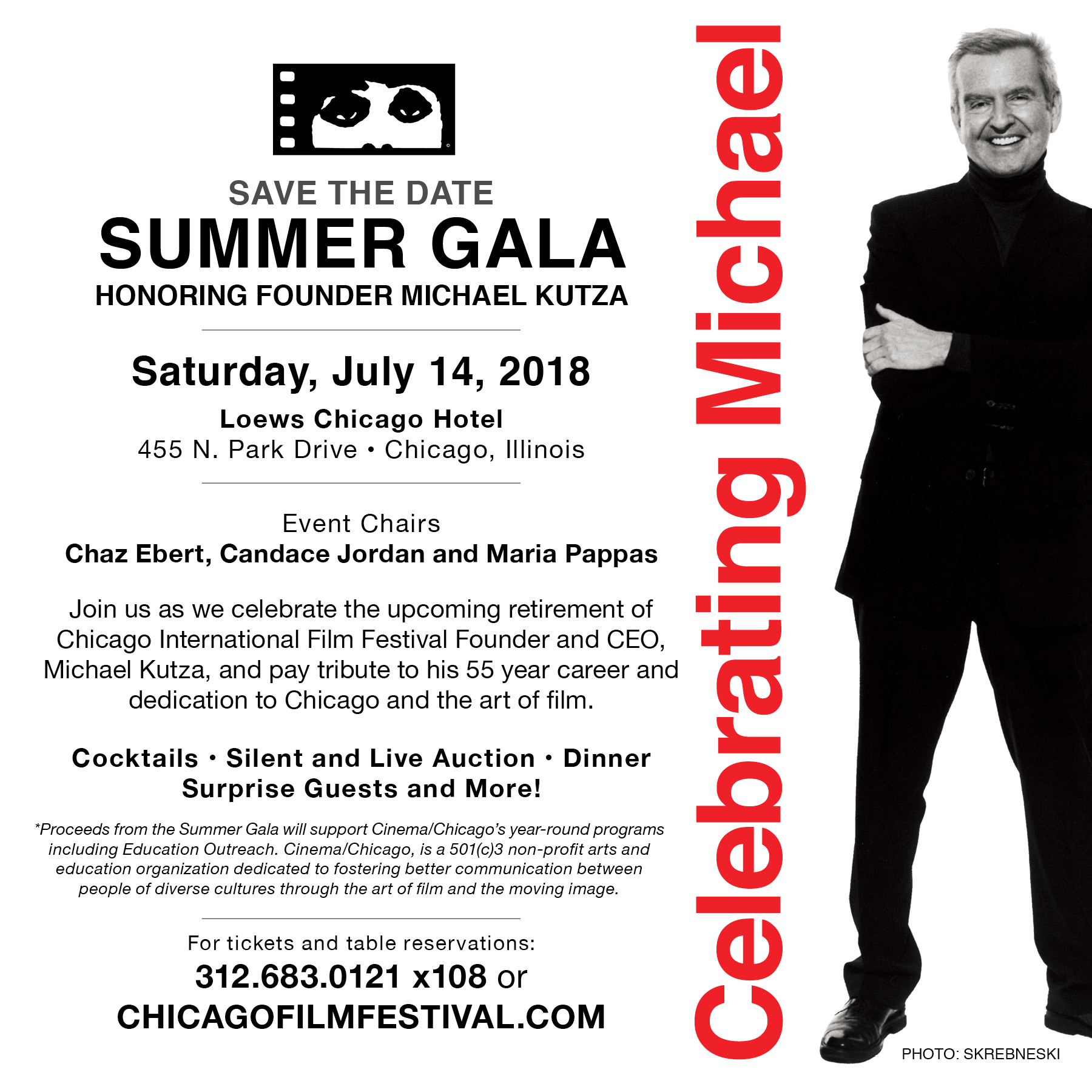

This Saturday, July 14, marks the perfect sendoff for the occasion, as the festival’s board of directors prepares to pay tribute to his storied career by “Celebrating Michael” at the Loews Hotel Chicago.

Chicago International Film Festival’s founder to retire after 55 years

“An iconic figure,” opines Randy Crumpton, a longtime member of the board of directors and co-chair of CIFF’s Black Perspectives programming.

“Michael’s contributions to Chicago go well beyond film itself,” states Betsy Steinberg, executive director at Kartemquin Educational Films and a former executive at the Illinois Film Office. “Through the festival and the important work with youth in our city, Michael’s leadership and vision is a true gift for our town.”

Mayor Rahm Emanuel concurred during the festival’s 50th anniversary in 2014, calling the festival “a central role not only in Chicago’s history, but the history of cinema itself.”

“The work that Michael’s done through establishing the festival has had such a massive impact on the cultural landscape of Chicago, as well as on the careers of so many filmmakers,” says Mimi Plauché, the woman replacing him as artistic director, a title Kutza has held longer than any other.

The Chicago International Film Festival, which he modeled after the one in Cannes, is the oldest competitive film festival in North America and screens 140 feature films from as many as 70 countries to about 58,000 patrons in attendance each year.

Aside from producing various year-round educational programs dedicated to the examination and promotion of film, Kutza is responsible for supporting the early careers of directors who’ve since gone on to achieve critical acclaim – including Golden Globes and Oscars – Martin Scorsese, Steve McQueen and Michael Moore being among them.

The CIFF world-premiered Taylor Hackford’s first two films (The Idolmaker and White Nights), an early version of Oliver Stone’s first feature film, and Milos Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. In 1997, Kutza also created the Black Perspectives program to honor and showcase the work of Black filmmakers.

“Film festivals these days – or any kind of enterprise, whether cultural, artistic, educational, scientific – have to be inclusive and I think that’s what this film festival is,” says Chaz Ebert, who along with Maria Pappas and Candace Jordan, is co-chairing Saturday’s event.

Kutza’s contribution “really needs to be celebrated,” says Plauché. It will be, as the board also plans to present Kutza with a Lifetime Achievement Award to add to the countless others on his mantle, including:

• the Silver Lion Award from Cannes for organizing a special section devoted to U.S. independent filmmakers;

• a Sydney Pollack Award from American Cinematheque honoring a person “who has been of critical importance and continuing influence in nonprofit film exhibition, film preservation and/or independent film distribution;”

• the Onorificenza di Cavalierato, the highest honor awarded to a person in the arts from the President of the Italian Republic; and

• being Knighted into the French Legion of Honour in 2015.

Actress Kathleen Turner, director Andrew Davis, and producer Paula Wagner are among the film luminaries scheduled to attend the gala and pay tribute. Following Kutza’s retirement as CEO, he’ll become Emeritus CEO. No replacement has been named to succeed him.

Still, Kutza is dismissive at the idea of any real “retirement.” You can’t use the word “transition” either without him scoffing. “‘Retire’ is such a weird word. I don’t know what it means,” he muses.

This sentiment isn’t surprising to anyone who’s seen him in action. I have for at least the last 10 years of covering the festival. Tireless at 74, the man literally works seven days a week. I recently sat and chatted with Kutza about his life in film.

N’DIGO: What was the first film that made you want to become part of the film industry?

Michael Kutza: I grew up in Austin on Chicago’s West Side and there was like one little movie theater. It only showed science fiction and horror films, so I was raised on that. But downtown, I think we only had two little movie houses that showed foreign films, and I’d venture in to see a Fellini or a Bergman…and those films would play for like six or seven months. I said, “There must more out there in addition to this.”

When I learned about film festivals and began entering them, I realized there was a whole world out there. We didn’t have anything here like that. That’s how it all began, really. I wanted something more. I started to see what was out there and I wanted to change things. It’s just that simple.

What was your thought process as a 22-year-old who’d come from a family of doctors?

I was studying to be a doctor. Your mother, your father, your aunts, your uncle, everybody in the damn family’s a doctor. All they do is look at you because they just know you’re going to become a doctor. My dad would say, “This is just a passing fancy, right?” because you’re going to become a doctor. He’s from an older generation, so I’d say, “Yes, Dad, I’m going to become a doctor.”

You’re faced with that very early in the game, so I got my degrees in biology and psychology. But I was making movies very early in the game, too. I knew where I was going, but they didn’t! We got a great understanding before they (passed away).

At what point did you learn to make films?

It was unusual to have a woman doctor back in those days, like my mother was. Her mother was a midwife in Italy. Here my mother was an OB-gyne doctor at Mother Cabrini Hospital, and she would go to these doctor conventions around the world and she’d carry a movie camera with her.

This is a true story: She’d carry a 16 mm, which was bulky, to take pictures everywhere she went. And then she’d come home after a long trip from Cuba or Italy or something…and say to me, “Okay, make this into a movie. The ladies are coming over next Sunday.”

I was starting to make little movies with music and stuff to show the lady doctors. And it was amusing. The other irony is my dad collected silent movies, Charlie Chaplin and all that kind of stuff. Television was relatively new back then, so I’m looking at silent movies at home and making little movies. And here I am at about 10 or 12.

Dad had the projector and my mother had the camera. It was easy to learn. If you look at the kids today, you can make everything on your cell phone. I envy what you can do today making movies. It’s wonderful. You do have to have some imagination and talent, but today the kids have got it made.

Meeting His Co-Star

Colleen Moore was one of your early mentors in helping you start the film festival. Talk about that. What was your elevator pitch to her when you told her you wanted to start a film festival?

Elevator pitch (laughs)? I’m not that kind of person. I’m a very shy, quiet kind of person. First of all, are you from an era where you know who Irv Kupcinet was from the Sun-Times?

Newspaper columnist. Kup’s secretary was Stella Foster, correct?

Absolutely, for many years.

My mother went to school with her.

Okay, there you go! So Kup, they called him “Mr. Chicago.” He really ran Chicago. He wrote political and showbiz columns in the Sun-Times, did television and radio – everything. He even covered the Bears football games with Jack Brickhouse.

Anyway, I made a film and got some reviews and awards at festivals. I’d met Kup at social events and he took a liking to me. He was very friendly. He’d call me Mike – and nobody calls me Mike – but I let it be.

I told him I wanted to start this festival and he said, “Well, Mike, you know, you should meet this lady. She used to be a movie star and she’s a widow now and you’d like her. She might like you. She’s been a widow too long. Maybe you can get her out of that.”

So he introduces me to Colleen Moore-Hargrave. I didn’t know anything about her, so I go to visit her. She lived at 1320 State Parkway. I meet this charming lady and I’m looking around her apartment and I see the photos and the paintings. She was a silent-screen comedienne. She was like Charlie Chaplin in the 1920s. She also had and helped popularize the flapper haircut.

She was very successful and one of the highest-paid females at the time onscreen. She left show business when sound came in because she was a silent-film star. Interestingly, as I got to know her more, I found out that A Star is Born is actually based on her life with one of her husbands.

So I meet Colleen and we hit it off immediately. I’m 22 and she’s she an older society woman at that time. Suddenly, I got her right back into who she was. She said, “You want to do this festival? I will help you do it. Let’s start meeting some people.”

I’m writing a book, so all of these things are on my mind right now. So Colleen says, “First of all, you’re too young.” She was friends with Harold Lloyd, and of course she also worked with Charlie Chaplin. She gave me a pair of black horn-rimmed glasses that Harold Lloyd used to wear and she said, “You’re going to wear these from now on and you’re going to be 27 years old from this point on.” And that’s how we began.

Her apartment was right across the street from the Pump Room in the Ambassador East Hotel. In my and Colleen’s day, the movie stars would travel from New York to Chicago by train, stay a night at the Ambassador East Hotel, usually have breakfast or lunch at the Pump Room, and take the next train to California. That’s how you went to the coast to make your movies. This is the tradition.

If you’ve been to the Pump Room, you know it used to be covered with photographs of all these movie stars. Colleen, living across the street, one day said, “I’m having Myrna Loy over for lunch.” I didn’t know who that was. Of course, I knew her movies, but I didn’t realize, “Okay, I’m sitting here having lunch with Myrna Loy.” The next day there was Joan Crawford.

These were all her old friends from the old days who wanted to come by and say hello because she’d left the business. It just went on and on. I met more and more film people and as it got rolling with the contacts and with her, we put together the film festival for several years. It was an extraordinary adventure for the two of us. And, of course, it didn’t make my mother very happy because suddenly I had acquired a new mother.

Oh, boy!

Well, Colleen was my mother now and my mother is still at the hospital doing all her work, so there became that little bit of friction. I didn’t think much about it because I spent all my time with Colleen and these movie people.

So your mom was a little bit jealous?

No kidding! And Colleen was a little bit jealous of my mother, too, because she had a “real” job. It was actually a very peculiar dynamic.

What did one woman think of the other?

I remember Colleen, of course, had a lot of jewelry from her various…husbands (laughs). And we had one gala dinner. My mother only came once to the film festival in her life. We held it at the Essanay film studios, where Charlie Chaplin worked. It’s still there on Argyle Street. It’s not a film studio anymore. I think it’s a school now. It was one of the first movie studios.

We had the gala and closing-night dinner there, where we honored the famous directors King Vidor and Stanley Kramer. Irv Kupcinet was the host at this 500-people blacktie affair that Colleen threw together with all her society people. We’d raised money to keep the festival going. And that was the event my mother came to with my dad.

My mom had a nice little diamond ring from my dad over the years. The first thing these two ladies did was start comparing their diamond rings. My mother wasn’t very happy when she saw Colleen’s. Little things like that I remember that made me laugh. I didn’t say a word, but it was very funny.

The Roger Ebert Factor

One of film critic Roger Ebert’s first assignments out of college was to cover the Chicago Film International Festival, right?

As far as I recall, his very first assignment out of the University of Illinois was to cover our festival for the Sun-Times. We became friends right away.

Talk a little bit about that relationship and how it culminated into the CIFF award named in his honor.

Roger was just a kid; I was just a kid. He’s writing about and loving film just as much as I am. And by then I was working for three different festivals. I was working for Italy in Venice and a festival in Iran because I had a knack for finding new – we didn’t call it independent films, we called them young American directors. I had a knack for finding them, and the world realized this kid in Chicago’s got a way into these films we’ve never heard of.

So I started finding them and dragging these directors and films to Venice, Italy, and Tehran. Iran was still run by the Shah at that time. One day I said to Roger, “You ever been to a film festival?” He said no. I said, “Well, you want to come to Iran?” This is whatever year it was.

So I brought him to Iran and he did his thing. He loved meeting Claudette Colbert and Cliff Robertson, people that he actually became friends with later in life for his own film festival out there in Champaign. And he had a ball.

I said, “Okay I’m doing Venice. Want to come to Venice?” He’d never been to Italy. He’d never been to the Venice Film Festival, and so that went on and he was on his own. He knew the routine. He’d just covered our festival and gotten hooked.

As the Chicago Festival grew, I always thought there should be a Roger Ebert Award – especially when he got sick – that there should be some memory of Roger. That’s why we developed the Roger Ebert Award and Chaz (his widow) keeps it going every year.

It’s really astonishing all the awards you’ve won from around the world. Of all the honors that you’ve been bestowed, has there been one that’s been the most humbling or meaningful in some way?

I’m Italian and Polish, the double Catholic and those kinds of things that go with it. And I’ve got to tell you that the chance to meet Sophia Loren back in the 1990s was amazing. I’ve met so many cool people, but she was very special and we’ve remained friends.

Collen was special, King Vidor the silent film director, Harold Lloyd, and Sydney Pollack. Oliver Stone has remained a really good friend. We showed his first film. These directors we’ve shown their early films and then they go on to become something. That’s the whole purpose of the festival. That’s why I started it: to discover people. And Scorsese…a lot of people are making videos for this tribute at the gala because they’re all working. They can’t come for one night, so they’re making videos and they’re saying some really nice stuff.

What have been your greatest achievements with the film festival?

I think just keeping it going, keeping the enthusiasm, keeping Chicago excited, keeping the board and sponsors enthused. It’s a never-ending battle. The achievement is keeping it going, keeping the dream alive.

Aside from meeting Sophia Loren, what are some other memorable moments in your career?

Just meeting any of these filmmakers I’ve admired so much in my life. I am in awe when Francois Truffaut comes into the office or we sit down and have coffee with Robin Williams or Steven Spielberg and just sit there and talk about normal kinds of things. Or if I drag Morgan Freeman over to La Scarola restaurant and have a ball. Knowing how real these folks are has been important to me. People only see the star-studded side, but the human being, the person that really is that person, has been something that really impresses me.

You have what most people would see as a dream job. You travel all over the world, hobnobbing with famous people. Why retire?

The reality is that when the festival began, I was “hobnobbing” with people who had not become famous yet because part of the game plan of the film festival was to discover these people before they’re anybody. And then, yeah, later they became famous and then, yes, then you did hobnob with famous people. But you were there before they were famous. That’s sort of the coolest part about the whole life of it.

What are you going miss the most about the job?

I’ll still see the new movies somehow. I love seeing new films, new directors. Will I miss seeing 300 films in a year? Yes, I’ll miss that for a while. It’s really funny, when Mimi and I come back from Cannes and we’ve seen three to four films a day, the first thing I do when I land in Chicago is go to the movies. I just have to see another film, another one, and another one…I love movies.

So how are you winding down? You’re not really winding down, are you?

I’ll never wind down, no.

So, what then does retirement look like for someone like you?

What will it be like is I’ll be working on a (behind-the-scenes) book; I’ll be consulting with people on their films or even Broadway shows. I do a lot of theater, so I’ll be involved in theater, as well. I won’t be traveling that much. I don’t travel that much right now. I focus carefully on where I’m traveling to for its purpose.

I’m not a person who relaxes. I’m a workaholic, so I’ll have to find something that keeps my “workaholic-ness.” If the festival needs me to consult, of course, I could always come back. But that’s not my plan. They’re in good shape. They can do everything without me. They will be just fine.