Christina Sharpe, professor of English at Tufts University, urges Black people to come to grips with our situation through the practice of “self and communal care” beginning with reading, study and collaboration. She terms this “wake work.”

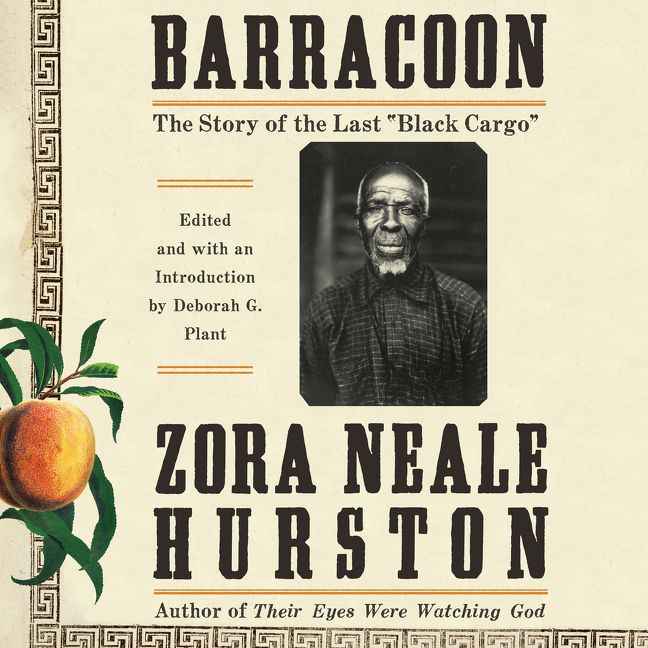

A good way to begin is by reading an 87-year-old, yet newly published book, Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo, by the late Zora Neale Hurston.

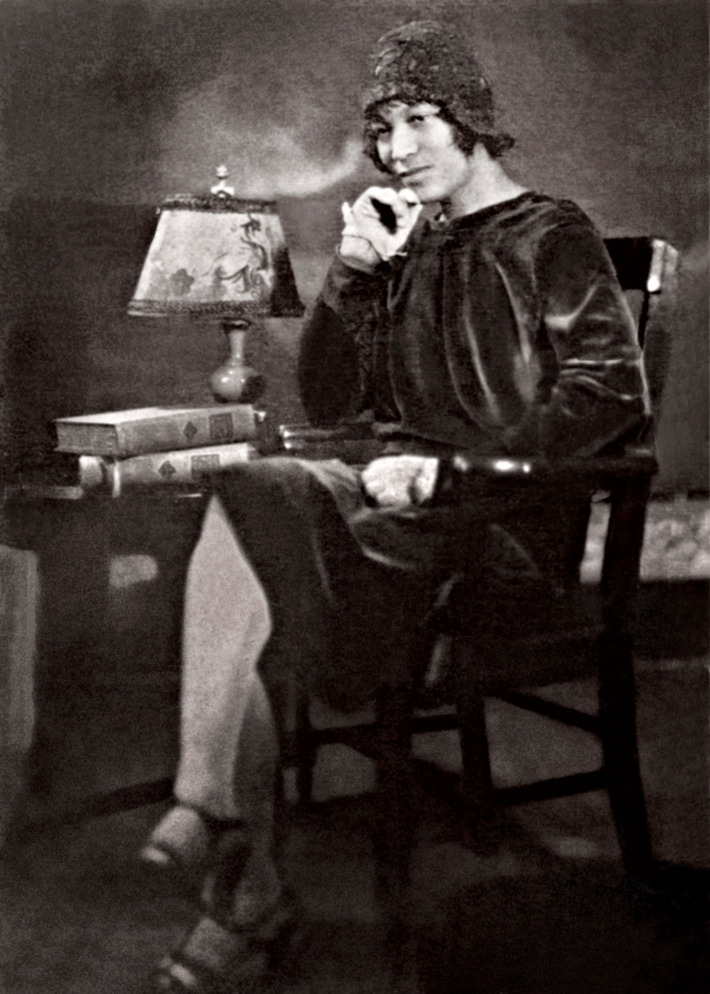

The author, who passed in 1960, did her fieldwork in the late 1920s by repeatedly visiting and interviewing an octogenarian ex-slave believed to be the last surviving veteran of the infamous “Middle Passage” from West Africa.

For decades, Hurston’s in-his-own-words manuscript of Cudjo Lewis’ experience lay unpublished on the library shelves of Howard University. Seems there was no popular market for the memories of an elderly Alabama Negro who spoke in the vernacular of the rural South.

Now, thanks to the brilliant editing of Deborah Plant, a Zora Neale Hurston scholar, we have an eminently readable first-person account of the trans-Atlantic ordeal that faithfully preserves not just the language, but the basic humanity of a genuine survivor.

Hurston’s writing is iconic. What she does with lyrical language – both hers and that of her subject Mr. Lewis – is akin to what her Harlem Renaissance peers Duke Ellington did with piano notes and painter Jacob Lawrence with canvas and oils.

But First Some Background

The African Diaspora in the Americas represents the largest forced migration in the history of the world. According to historian Paul Lovejoy, between the years 1450 and 1900, more than 12.8 million Africans were enslaved. Other scholars put that number closer to 60 million when considering those thrown overboard, forgotten and uncounted.

Britain abolished the African slave trade in 1807 and the United States in 1808. However, an Alabama shipbuilder and slaveholder named Timothy Meaher built the ship Clotilda in 1860 and, in violation of the law, navigated to the west coast of Africa in search of people to enslave.

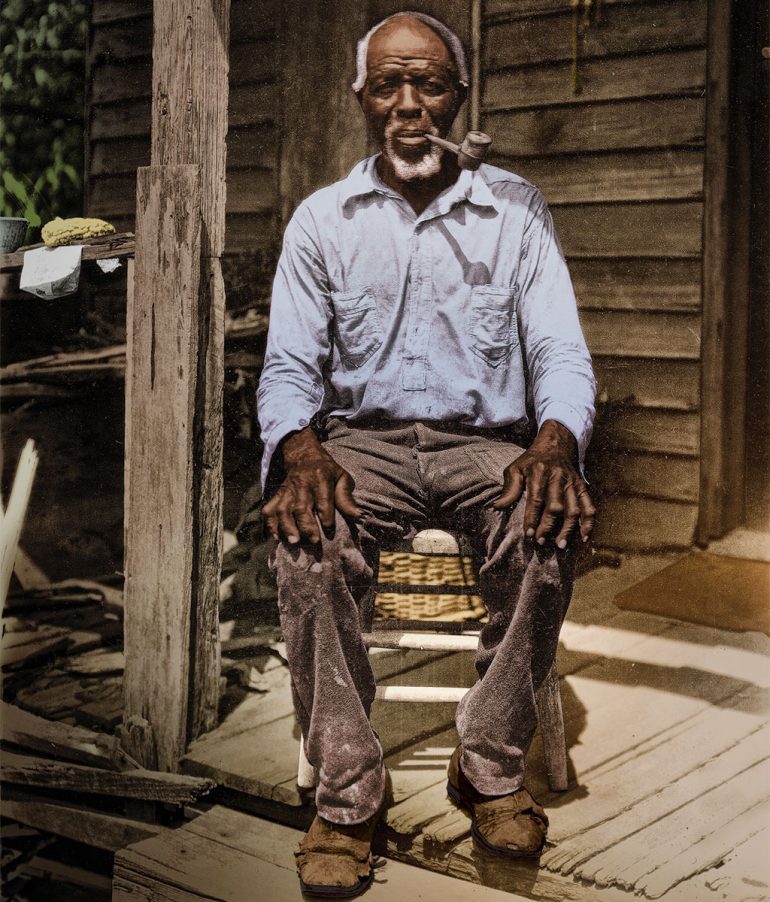

Oluale Kossola, whose slave name became Cudjo Lewis, was among 116 Africans abducted, sold to Meaher, and loaded aboard the Clotilda for the trip to America.

At the age 67, Cudjo Lewis told author Hurston about that trip aboard the slave ship and, almost as harrowing, the experience of being Black in the Deep South following the Civil War.

The Middle Passage And More

In succession in the book Barracoon, we learn about:

• Lewis growing up in his African village until the age of 18;

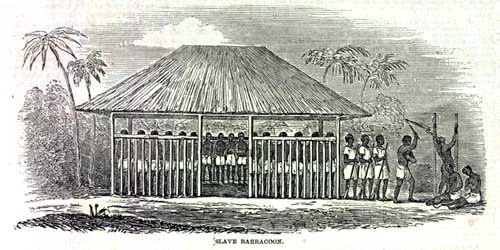

• His capture and survival in a “barracoon” – which was a holding pen for slaves awaiting shipment;

• Passage across the Atlantic Ocean from Africa to America;

• Life as an Alabama slave;

• Post-bellum “freedom” and Lewis’ confusion about what to do and where;

• Informal agreements among many Africans to live together, despite tensions among different tribes-of-origin;

• Refusal by his former slaveholder Meaher to provide Lewis with even a small plot of land;

• Creation of an African town;

• Loneliness, marriage, family, and the death of loved ones; and

• Encounters with Alabama’s Jim Crow laws.

Every chapter of Lewis’s story is suffused with the power of a first-person re-telling and, importantly, the humanity of his speech.

For instance, Lewis goes to Meaher and asks for some land for his people after freedom. They don’t have money to go back to Africa or the resources to buy land. He hopes Meaher can give them a small parcel based on their years of unpaid servitude. From Hurston’s writing in the book:

“Capn Tim, you brought us from our country where we had lan. You made us slave (5 years and 6 months). Now dey make us free but we ain got no country and we ain got no lan! Why doan you give us a piece dis lan so we can buildee ourself a house? Capn jump on his feet an say, ‘Fool, do you think I goin give you property on top of property?’”

Thoughtful Black readers will find in this exchange certain similarities to modern-day discussions about government benefits, affirmative action and reparations. Lewis was exploited by Meaher for over five years with no pay and the added trauma of being seen as and treated as less than human. At freedom, he seeks some land on which to farm and live.

But the slaveholder is baffled. Why should he give property (land) to his former property? Lewis, though freed, remains sub-human and deserving of nothing for his past treatment, according to Capn Tim.

Present-Day Denial

It wasn’t until a hundred years after this exchange that President Lyndon Johnson acknowledged that a national program of affirmative action was needed to redress the damages of slavery and subsequent Jim Crow discrimination.

LBJ’s assertion is still being challenged in the courts and at the polls. We know well of this struggle. Former Congressman John Conyers attempted for decades to hold hearings on reparations for the descendants of Black slaves. Never happened.

To illustrate the denial depth of the slaveholder plunder and abuse, today, as they open a new Thomas Jefferson facility in Monticello, there are still some white Jefferson descendants who refuse to acknowledge kinship with the offspring of Sally Hemmings, Jefferson’s slave mistress. With DNA proof, there is double kinship between them: Jefferson’s father-in-law John Wayle fathered Sally Hemmings by his slave mistress Betty Hemmings.

In the book, Barracoon editor Deborah Plant provides an invaluable glossary, along with helpful notes and an afterword that offers context and clarity on critical elements of Hurston’s opus.

Along with the authentic first-person narrative of Cudjo Lewis, Plant’s editing achieves what may be the most concise, important, informative book on the subject of African slavery yet published.

Plant writes of Hurston’s achievement: “In her endeavor to collect, preserve, and celebrate Black folk’s genius, she was realizing her dream of presenting to the world, ‘the greatest cultural wealth on the continent’ while contradicting scientific racism…the body of lore Hurston gathered was an argument against such notions of cultural inferiority and white supremacy.”

Inspired To Action

This reader/reviewer is inspired to do several things after reading this book:

1. Donate 25 books, 25 e-books and 25 audio versions of Barracoon to Chicago’s Urban Prep Academy, where my son Tim is founder/CEO and wants to revive a Real Men Read program.

2. Urge all public and private high schools to make this book required reading.

3. Ask Goodman Theater Director Chuck Smith to coordinate a reading of the Cudjo Lewis narrative onstage.

4. Approach WVON radio about airing serial installments of the audio book.

5. Suggest that Northwestern and Roosevelt universities build courses around, or integrate into existing curricula, Hurston’s masterpiece.

6. Approach Professor Waldo Johnson at the University of Chicago about hosting a Barracoon Blast at the college that would be co-sponsored by Black businesses.

The rediscovery of Zora Neale Hurston’s chronicle of the ordeal of Cudjo Lewis – an ordeal that remains an unhealed wound on a body politic that would sooner forget – is a literary event of the first magnitude.

Black youth talk of being “woke.” Let Barracoon be for us a wake work watershed.

(Paul King is a construction consultant and member of Chicago’s Business Leadership Council.)