Muhammad Ali 1942-2016

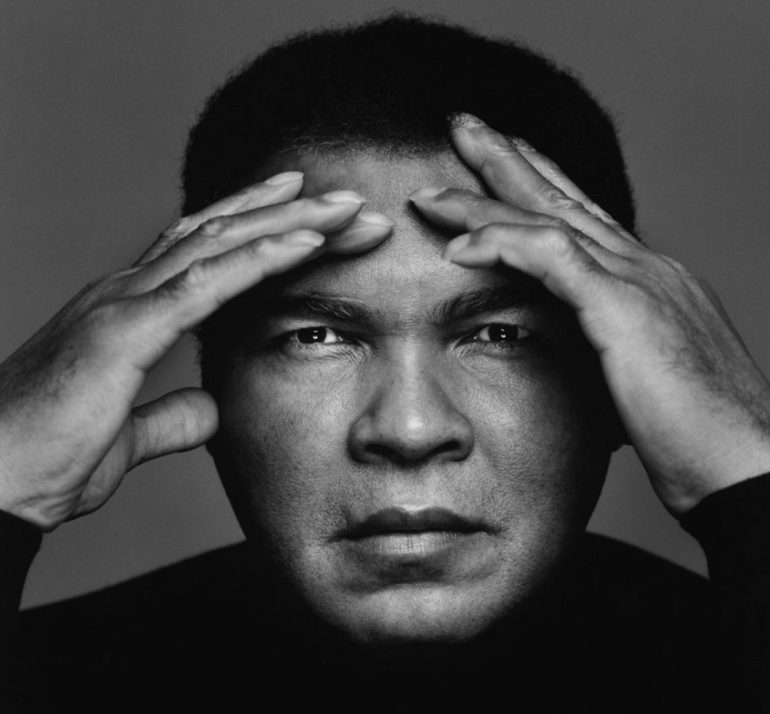

With the passing of Muhammad Ali, America has lost a champion of a man. He was magnificent, awesome, a stallion.

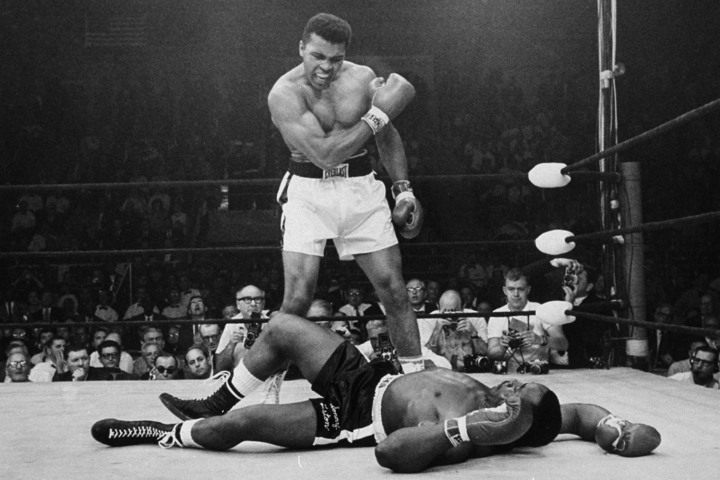

Mastering the boxing ring, Ali not only changed the sweet science of boxing but the face of sports. He had a presence like no other, a prince prancing, a boxer dancing and the king of the jab.

He could give a punch, he could take one, and he was a mastermind at psyching out his opponents, sometimes to the point of embarrassment.

Ali said he was pretty and he was, but he also had a little nasty streak in him as he belittled, teased, angered, and ridiculed his opponents all in the name of the promotion of the fight. But sometimes it was personal, as in the cases of Floyd Patterson and Ernie Terrell, whom he beat mercilessly while shouting, “Uncle Tom, what’s my name?”

Ali was a fighter full of confidence, a man assured of himself and his power. He was The Greatest, with no hesitation or reservation – in his own words, and everyone else’s.

A graceful and powerful, demanding, commanding giant, Ali changed the game as he broke every rule on the way to becoming a legend.

The Red Bike

In or out of the ring, Ali was the same. A jokester, a promoter, a marketing dream, witty and a street poet. He was a hell of a guy, by all measure.

His start in boxing came because of the theft of his red bicycle when he was 12. He wanted to beat up whoever stole his bike. A policeman suggested that he take that anger into the gym and also learn to fight if he indeed was going to pursue that intention.

That policeman, Joe Martin, trained young men to box in his spare time. The pre-teen Cassius Clay, his birth name, turned out to be a natural boxer. His talent was obvious and a career in boxing was born because of a policeman who didn’t shoot young Black boys.

Cassius rose to became an Olympic star and champion. He won the Golden Gloves in 1956 and the Olympic Gold Medal in boxing in 1960.

A syndicate of businessmen from his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky put together a business organization and plan to back the boy who would become Muhammad Ali.

He was serious and disciplined and practiced his craft all the time. Ali was a perfectionist. I saw him once in an exhibition at Navy Pier. His movement was magnificent; his grace was like a butterfly, and his body was perfectly sculpted. He used to run in Washington Park early mornings. I use to see him doing his roadwork as I was going to work.

Objecting To Vietnam

Ali was much more than the greatest boxer, the greatest sportsman of our time. When it was time to be drafted in 1967 to fight in Vietnam, he flatly refused.

At the time, Ali declared to white questioners at a press conference: “If I’m going to die, I’ll die now, right here fighting you. You my enemy; my enemy is the white people, not the Vietcong. You’re my oppressor when I want freedom. You’re my oppressor when I want justice. You’re my oppressor when I want equality. You won’t even stand up for me in America because of my religious beliefs, and you want me to go somewhere and fight, when you won’t even stand up for my religious beliefs at home.”

He added of the Vietnamese, “They never called me nigger; they never lynched me; they never put no dogs on me; they never raped or killed my mother or father.”

He thus summed up the Black man’s position. White media crucified him for it, but Ali stood firm and tall in the confrontation.

The Lost Title

The politicos and the boxing commission stripped him of his title, however, for refusing the draft and they did it at the height of his career. He didn’t fight for three years, during the apex of his prime.

He was also broke being deprived of his livelihood, so Ali toured the college circuit, making speeches. He rose to the occasion. His title was gone, but his manhood was intact.

He told the boxing commission to come get the belt that was encased in his living room in his bungalow on south Jeffery Boulevard here in Chicago.

White America was angry, of course, at the audacity of this uppity Black man. Mainstream press hammered him. It was pretty much old white men who were extremely critical and sometimes brutal to young Ali.

The likes of a Black man standing up like Ali was did not fit the docile attitude they were used to in their Negroes. He was arrogant, strong, angry and right.

He was out of the box and in his own way, he challenged America’s power structure at every turn. He used his voice. It was simple and ironic.

The greatest boxer in the world saying I refuse to fight the Viet Cong. They are not my enemy. He was clear on who he was and where he was. A hero was in the making, speaking to the common man.

Thanks, Champ, for showing us how to fight in life’s ring.

Black America and others embraced him. Black America was watching a Black man stand on principal. He said he would go to jail before going to the army to kill other brown folks, poor folks. He meant it. He was forceful. This was the making of his greatness outside of the boxing ring.

Ali stood up for his beliefs and fully exercised his American rights as he challenged the system. He was a conscientious objector and part of the objection was his religion.

Ali was a member of the Black Muslims, under the strict guidance of The Honorable Elijah Muhammad. Major media referred to them as a “Black separatist group” and white America considered them a potential terrorist organization.

The Black Muslims were disciplined, focused and serious in bow-tie uniforms, looking like an army. Ali followed his religious order and made the world respect him.

It was when he joined the Nation Of Islam that he dropped what he called his “slave name,” Cassius Clay, to rebrand himself as Muhammad Ali, a new man.

The white news media, particularly his broadcasting friend Howard Cosell, joked with him about it. Ali would give Cosell an exclusive interview on ABC-TV and play with his toupee, making Cosell hold onto his head. Eventually, the media and the world took Ali seriously as he proclaimed his new name.

The world will study The Champ’s record for years to come – 56 victories, 37 by knockout, and five defeats. He is the only boxer to have won the heavyweight title three times.

His legendary fights, the Thrilla in Manila with Joe Frazier and the Rumble in the Jungle with George Foreman, were brilliant extravaganzas.

Ali’s N’DIGO Gala Honor

In 2005, the N’DIGO Foundation, at our 10th celebration, presented Muhammad Ali with the Lifetime Achievement Award at the newly opened Millennium Park.

We had tried for three years to bestow such an honor on Ali, working with his team of Troy Ratliff, Cleve and Belvon Walker, and Ali’s wife Lonnie. The challenge was in setting the right date when Ali would be available. We finally made it.

I realized that Ali had almost never been honored in Chicago before because of prevailing racism, religious and political maneuvers.

Mayor Richard J. Daley did not want the increasingly popular Muhammad Ali to be recognized of fight in Daley’s Chicago. He blocked Ali from fighting here in the city where he lived – despite the revenue that such an event would have brought to the city.

He also tried as much as possible to block any awards to Ali that would attest to his credibility in any way. Ali was too popular for Daley’s taste, but more importantly, Daley was not fond of the very well disciplined religious organization – the Black Muslims, headquartered here in Chicago – that was behind Ali.

The Daley mindset of dealing with such characters and situations was to stifle them before they could take hold and rise to become a political force.

Daley was successful with his political cohorts, but Ali was the champion of the people. He was rooted in the community. He walked the streets of the South Side of Chicago like a pied piper.

He went to the clubs, like the Dog House and Tiger Lounge. He went to the Muslim mosque and the Muslim restaurant on 83rd and Cottage. Ali played with the kids on the playground and the cats on the corner.

Crowds gathered as he shadowboxed and preached. He went to Operation Breadbasket regularly with Rev. Jesse Jackson. He was rooted as a Black man. No excuses. No explanations. He was Ali and he was not confused.

He preached self-help. He preached love your brother. He preached protect your women and your children. He preached independence. He preached Manhood 101.

When we were preparing for the 2005 Gala, he and Cleve visited the N’DIGO office every day for two weeks to help. One Tuesday, which is the day our newspaper goes to print, they came by and I said, hey guys, we are working for real today.

Ali said he came to help. Steve Johnson, our art director, began to hand him proofs. We had him reading proofs, looking for typos and corrections. He loved looking at the pictures we were running that issue. They stayed with us until we put the paper out. Amazing.

They came back the next day at lunchtime. We all had lunch, and Ali told us jokes and did magic tricks. We were in awe.

I told him he was handsome. He said, “No I’m not, I’m pretty … and so are you.” “Are you flirting?” I asked him. “Yes,” he said smiling. “I’m still the champ, you know, and women love me.”

He was slower, his speech quieter, his steps measured and deliberate. But he was Ali. That day after they left, I cried like a baby. He was now great, in another way. Life changes but the essence of his real greatness remained very much intact.

I was happy that we were honoring him. The next day, he and Cleve came to work. Dolores Elliott, the coordinator of that year’s event, suggested we plan some actual Gala work for Ali. She said, give him something to do.

I asked them to go sell tables. They did, and for the next few days, they had luncheons with their sports buddies and business types and sold tables and sought donations. Cleve and Ali were hosting meetings in Chicago’s private clubs.

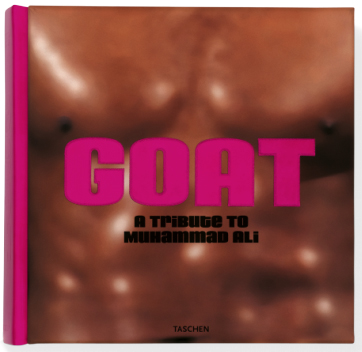

One day, Ali brought us a huge picture book of himself in the boxing ring. It was one of the largest books ever, and he said it would be very valuable one day.

That book, “The GOAT, The Greatest of All Time,” cost $1,000. It was a gift. He signed some pages to add value. Then the next day, he and Cleve bought us red boxing gloves that he signed. He told me they would be very valuable. They auctioned to Cheryl Burton at the Gala at a very hefty price.

That book, “The GOAT, The Greatest of All Time,” cost $1,000. It was a gift. He signed some pages to add value. Then the next day, he and Cleve bought us red boxing gloves that he signed. He told me they would be very valuable. They auctioned to Cheryl Burton at the Gala at a very hefty price.

Ali and Cleve decided that we should have a Muhammad Ali Scholarship. It started as one scholarship but grew to four. Troy Ratcliff assisted in making it happen with kids from the Better Boys Foundation. Ali had rules, though. The scholarships had to go to bad boys from the West Side. That was his stipulation. We complied.

The night of the Gala, Sunday, June 19, 2005, was glorious. The weather was Chicago summer beautiful – a perfect day for an outdoor event to honor a champ.

Ali was excited. We rehearsed for a couple of days with him and Cleve. Our timing was perfect. We had it down. The Gala evening when he came to the stage, the crowd roared, “Ali, Ali, Ali!” He loved it.

The International press was in attendance. Rev. Jackson stepped up to raise Ali’s arm in championship fashion. Ali was the champ again – champion of the people. He was loved. He was always the champ, no matter what. Our practice routine went out the window.

I found out that Ali wanted a globe. The jewelry store, Tiffany, told me to come to the store and pick out a gift for him. He was presented with a crystal globe from Tiffany as his award.

Ali was touched and asked me how did I know he wanted a globe. I couldn’t believe I had just given The Champ something that he really wanted. It was special.

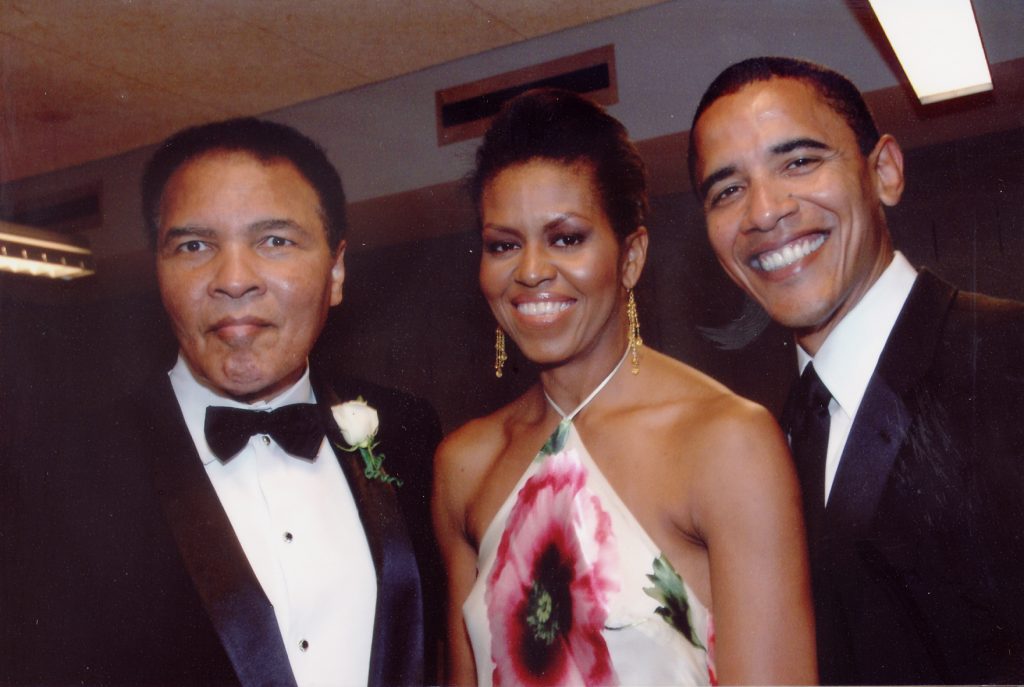

Barack and Michelle Obama were the Gala Chairs that year. They met Ali for the first time. The stage was hot and backstage, Ali was boxing with everybody and taking photos. He was having a ball. He boxed with then Senator Obama, Rev. Jackson, fellow honoree Michael Scott.

They went to Gladys Knight’s dressing room – she was the Gala entertainment that year – and totally disrupted her while she was getting ready to perform.

Ali flitered with all of the women. He took pictures; he shook hands. He was warm and receiving and funny. He was a riot. We loved him, and he loved everybody. He gave me a hug after it was over and I cried. He said, let’s go back to the hotel and party. And we did.

In Retrospect

How could this city, the city of big shoulders, never formally honor this icon? I still ask myself.

I am so glad that we took the time to do so. Racism and politics get in the way and you must always overcome it by doing what is right.

Viva Ali! He will live forever. He is the stuff of legend and we probably will never see another Ali in our lifetime. I am glad I lived in his era.

He lived with grace and dignity, no matter his plight. His wife, Lonnie, deserves a medal. She kept him in dignity and made his life lovely as he traveled the world with his humanitarian efforts. His friends adored him and protected him as he stayed active as Champ Ali.

There was probably nothing on Ali’s bucket list. He lived full. He planned his legacy. He prepared his museum in his hometown of Louisville; he saw some of his books and he even planned his funeral services, private and public.

President Bill Clinton and Billy Crystal will deliver eulogies. Ali lived to the end. His daughter reported that after his body functions shut down, his heart kept on beating for 30 more minutes. His constitution was just that strong.

Bravo, Ali! The Greatest. Thanks, Champ, for showing us how to fight in life’s ring.