Gallery Guichard is an elegant contemporary art gallery, owned by Andre and Frances Guichard in a unique, South Side Chicago community called Bronzeville. The new constructions can’t disguise the fact that there are still poor black folks living in Bronzeville. Once a safe haven for blacks during the Great Migration for housing, businesses, and a hot nightlife; it was regarded as the “Black Metropolis” for southern blacks who migrated to Chicago. But, by the 1970’s until the early 2000’s it was difficult to recognize the neighborhood blocks with any historical reverence amidst the litter of liquor stores, vacant lots, and street life. At that time, I and other south siders nicknamed it the “low end”.

The spurt of renewal arrived alongside the dismantling of many Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) properties, namely the Robert Taylor Homes. The community area has brought forth a resurgence of neighborhood revitalization in the past decade with the onset of a new Black middle class who are the new construction condo or town home owners. Many of them are doctors, lawyers, and business owners in blended households who have reignited the old Negro promise of having a south side “Black Metropolis,” not far from the Hyde Park home of the first black President. This is a perfect place to have a beautiful art gallery, and it’s the perfect time for an artist, called Ti- Rock Moore to unpack and explore the truth about racism and black oppression from the lens of a white person in a Black owned art gallery, in a predominately Black community in the heart of Bronzeville.

Last Summer was when I first heard of the controversial art exhibition “Confronting Truths: Wake Up” at Gallery Guichard. A low quality video began to circulate of the replica of Mike Brown’s body on the floor with police tape. It went viral. The video was shocking. Many people questioned if it was “real art.” I had to see the full context. I made several trips that summer, mostly alone to see the exhibit. The first image, near the gallery entrance was the replica of Mike Brown’s body and the crime scene, juxtaposed with a young Eartha Kitt recording. Eartha is looking, crying, almost praying down on him as she sings: “Angelitos Negros,” or “Little Black Angels.” This piece was only part of the story – an art exhibition complete with 50 compelling images that boldly confronted past and present truths. It was a deep, emotional, and provocative journey that explored and unpacked the atrocities of racism and white privilege in America. This was when I discovered the work and message of artist Ti-Rock Moore.

I contacted her after the exhibit. We kept in touch. I asked for an interview. What I got was deeper than an interview, but more like her dissertation on protest art, racism, and the journey of becoming an artist called Ti- Rock Moore.

Ti – Rock Moore : “Thank You for doing this interview with me. I’ve decided to answer your questions quite freely, which is atypical for me. Because I am not a writer, my answers will also be quite long, but I really want to give you the whole story, and not just sound bites.”

Ti – Rock Moore : “Thank You for doing this interview with me. I’ve decided to answer your questions quite freely, which is atypical for me. Because I am not a writer, my answers will also be quite long, but I really want to give you the whole story, and not just sound bites.”

N’DIGO: How did you become a professional artist later in life?

TI-ROCK MOORE: This is an important question, because I did not want to be an artist, I had no aspirations to become an artist. It’s not as if I was sitting around an art studio and needed to come up with subject matter for work, or that I needed subject matter and chose the dehumanization of people of color as subject matter for an exhibit. I was not in these positions because I wasn’t an artist and wasn’t looking to be one either. It’s not as if I was bored in ‘my later years’, and decided to become an artist. I am an activist first, and foremost. I did not produce art until a couple of years ago. The protest art I have made is a manifestation of my activism. Specifically a manifestation of the well thought out, yet primitive, hand made signs I used to carry in protests and marches that were actually great pieces of protest art.

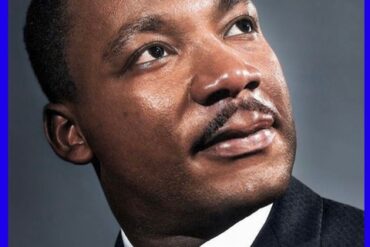

Me at the 50th anniversary March on Washington, just after the murder of Trayvon Martin (therefore the skittles surrounding the crosshairs), before I was making art formally).

I had no intention of, or longing to become an artist at any point in my life, including “later in life”. Maybe I had no desire ever to become an artist because I grew up in the art world. Both of my parents were full time professional artists here in New Orleans (that did succumb to making art that appealed to and sold to tourists—ugh, what a bore).

I was raised by two incredible, formally trained amazingly talented artists. And I think that’s why I shunned away from making art. Don’t get me wrong, I love visual art, and have always been kind of obsessed with conceptual and installation art and artists. But I had no interest or aspirations ever to become an artist.

As I said, my protest art and working as an artist manifested itself directly from my activism!!! You see, I have been an avid, some may say rabid activist since my 20’s (I am presently 56 years old). In my 20’s and 30’s, the 1980’s and 90’s I was a gay rights activist. I was young so it was all about me, right! My activism was about me and my community.

I know that the inhumanities and injustices that the gay community in NO WAY COMPARE to the battles fought by people of color in this country for the last 400 years. And although I was gay and out, despite the struggles, I was and am aware I had my whiteness to fall back on!!!

I learned a lot from my gay rights activism though. I learned you have to speak up, and out, and loudly, and often, that you have to take risks with activism, and you must disrupt, disrupt the status quo. I learned how hard it is to handle the hate you not only live with because you’re gay, but the hate that is spewed at you for speaking up for basic human rights. I gained a lot of insight and strength speaking out, particularly in the 80’s, when Reagan was president, and a large percentage of the gay male population was dying of Aids. I refused to be silent, just like now. I learned not to be frightened of speaking out for what I believed was humane and I learned how to be a very vocal activist. I realize now my protest art speaks louder than I ever could, and I that I won’t be censored by someone else’s hate or misinformed opinions, just like I was not silenced in the 80’s and 90’s. During that time, when I was doing of a lot of gay rights activism, I was a member of a group of very strong lesbian professional women. They were older than I was, and they were brilliant and successful activists.

Gay rights has gained significant momentum, and times have changed drastically for the LGBT community. When I was young, the battle I chose to fight with everything I had in me was all about me, and all about me being queer. I have been an activist for nearly 40 years, that’s who I am and what I do, and as I have grown older my interests have become less about me. I think that’s just the natural progression of life. But my point is I had no aspirations to become an artist. My protest art is born of, a direct consequence of, my activism. I was and am an activist, an activist that was directly affected along with my fellow New Orleanians by KATRINA.

I studied 4 to 5 hours every day since Katrina, for the last ten years. I study anything I can get my hands on that can teach me and help me make sense of the control, abuse and policing of black bodies in this country. This includes STUDYING the last four hundred years of American history , current events, theses ( on everything from white supremacy to white fragility), and books(my top 4 books right now are Brainwashed, The New Jim Crow, Between The World And Me, and the book on my favorite artist, Thorton Dial, ‘Hard Truths”. And this is where I get my inspiration for my work. I write down lots of ideas while I am studying, making lists that I am refining constantly. Lists on ideas for pieces, and lists on ideas for titles. And it is through this studying that it has become clear over and over to me, that human cruelty in this country is rooted in the entitlement of white men in power. And that there is a very complex set of systems, regulations and institutions fixed to keep the white man in control. And this is how my own race is pivotal to the conversation that evolves around my work. I know that I am in a delicate position as a white person to speak of these truths, but someone from the perpetrating group must stand in the crowd and call out the perpetrators, even if standing makes me a target for so many.

NDIGO: How did you begin?

TI-ROCK MOORE: So about 2 years ago my best friend was over, and loved my signs, and some very primitive pieces of protest art I had made, and suggested that we invite some friends over to see it and have cocktails. So the following Friday I did that, and my friends were kinda blown away. I’m not thinking it was so much the art, but it was with my message. They suggested I refine a few pieces and try to get into the museums or gallery shows here in New Orleans. So I did refine a few pieces and answered some ‘calls for artists’.

TI-ROCK MOORE: So about 2 years ago my best friend was over, and loved my signs, and some very primitive pieces of protest art I had made, and suggested that we invite some friends over to see it and have cocktails. So the following Friday I did that, and my friends were kinda blown away. I’m not thinking it was so much the art, but it was with my message. They suggested I refine a few pieces and try to get into the museums or gallery shows here in New Orleans. So I did refine a few pieces and answered some ‘calls for artists’.

When I was making these pieces, I had no idea that my protest art would go anywhere!!!! But immediately 2 pieces were taken into a show at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, and one piece was taken into the New Orleans Contemporary Arts Center, which was having a contest sponsored by Bombay Sapphire, with the winners piece to be shown at Art Basel in Miami (this is how I met Andre and Frances Guichard, and why I was fortunate to be asked by Andre Guichard to represent me as an artist). I won that Bombay Sapphire contest and went to Miami, and the trajectory of my protest art has been crazy amazing since then. I was in 5 shows in 2014 and ten shows in 2015. So my intent was never to make art to sell. My full intent was to make art that speaks – LOUDLY! Money has not been my motivation at all. I presently am honored to have 40 of my pieces showing at the Houston Museum of African American Art. I see the body of work I have made much more as a museum exhibit, which travels hopefully internationally as a whole. It is meant to be shown together, although separate pieces do travel to exhibits around the country to be shown separately. I have invested heavily in producing this body of work, and some pieces have sold, but I have not regained a fraction of my investment. That does not matter to me, because this is not about money and has never been. It is about activism, and I believe that’s why it is so visceral. It is about the body of work as a whole, speaking to the viewer. But since the work has now gained international attention, hopefully I can continue on producing, BUT IN ORDER FOR THAT TO BE POSSIBLE the pieces need to at least start paying for the production costs. And I make no excuses for that, because that is how artists make art, and keep food on their tables. I am an activist that produces protest art now, and I produce this art to do just that -protest-!

I define my art as protest art, some call it political art. My protest art IS A GESTURE OF ACTIVISM. My mission in my art is to loudly confront the truths of our fixed institutional structures and racist systems that support and keep white supremacy intact. My intent is to bring these devastating truths to light. My artwork is literal, but protest art cannot be subtle. I feel that it is necessary for white people to take accountability for our role in racism, and our role in the fight against racism, and after all, more is more. I believe advocacy on white people’s behalf is absolutely necessary in getting anywhere, after all, we are the perpetrators. I want to change the conversation in America, predominantly about how white Americans engage in debilitating passivity (denial) when it comes to our role in racism, injustice, and the brutal violence that is faced by people of color every day in this country. I attempt to express in my work the inhumanity, dehumanization, violence, oppression, hatred and poverty which I believe are engrained in America’s fabric to keep the white man in power.

THIS IS THE GREAT MORAL ISSUE OF OUR TIME. White privilege and white power and white supremacy are what I’m responding to in raising the realities of racism either symbolically or overtly. I hope to provide a reflection of the perpetrators to the perpetrators. This is not so as to center whiteness, but to take accountability. My responsibility as a white ally, activist and artist is not to simply acknowledge racism outright, but to target those namely fellow white folk who turn a blind eye to systemic oppression. My pointing out these brutal realities is in part controversial because our expectations of white Americans remains in the realm of silence and mediocrity. Speaking out as a white person is immediately associated with the very entitlement I’m trying to dismantle.

NDIGO: Is your message or art different for whites than black people?

TI-ROCK MOORE: Yes, as a white person, I’m not in a position to target black audiences in my message because I will never know what it’s like to experience the world as anything other than who I am. It would be unjust to project any of my ideas about racism to an audience that is outside of my lived experience, particularly when the subject matter is racism. And as a Black American if you see my work and assume it’s targeting you, it may very well offend you, because you are already conscious of these realities. IDEALLY I wouldn’t want to exclude anyone, but someone has to target the perpetrators of racism. What I’m doing in aiding the movement is necessary because white folks need to see this and acknowledge that it’s happening once and for all. And between you and me, there are a lot of white people that just don’t listen to black people!!! And this is part of the importance of everyone bringing awareness to light about these ugly and brutal truths!! And it is pathetic that the art that people of color have made for a very long time dealing with these truths goes unnoticed. But that’s the problem!!!— and again this is a manifestation of the systems to keep white people in power, and in denial. Denial that masquerades as entitlement, entitlement that is racism!!!! I focus on creating art that brings into collective awareness these unpleasant truths.

NDIGO: What do you feel about your art?

TI-ROCK MOORE: Yes, I do, like some pieces much more than others. I just believe some of the pieces are better than others. And, I do believe one of the reasons that I got soooo much press in Chicago was my installation ‘Angelitos Negros’. I want to share with you how I feel about this piece.

‘Angelitos Negros’ is an art object, a powerful one, an important one, a necessary one as reflected by the volume and magnitude of dialogue it created internationally while in Chicago. The part of that installation that was initially targeted by the media, was Michael Browns likeness which we all know by heart from our computer and TV screens. But what gives this installation most of its force is the beautiful and fierce Eartha Kitt singing the racially evocative song ‘Angelitos Negros’ or ‘Little Black Angels’, an American ballad of Black Power. To just read the lyrics of ‘Angelitos Negros’ on paper you miss the complex concoction of emotions Kitt embodies in this installation. She references seemingly the whole of art history as discriminatory thru her grief and defiance, insisting on her due from artists.

NDIGO: Do you ever feel that you’ve gone too far or something is too offensive?

NDIGO: Do you ever feel that you’ve gone too far or something is too offensive?

TI-ROCK MOORE: My intention in presenting this piece in a gallery setting was to invoke a larger debate. I apologize to anyone in the Black community that I have offended. Please know that I do not take ownership over Michael Brown’s body, and the re-victimization I’ve been accused of was meant to be a gesture of activism and a demand for change and justice. However delicate my role as a white artist may be, activism requires major risks to make progress. My desire was to mark this tragedy as one of great historical significance in acknowledgement of the event that ignited the modern day civil rights movement, to commemorate this young man, and to call attention to the racial injustices that remain so devastatingly relevant today. The upheaval that this work raised is a part of a very important larger conversation and it is necessary to observe how despite some of our polarized convictions, we arrive at the same conclusion. This young man’s image is not simply a part of a murder scene, it has become a public symbol of detriment in this country. AND NOT PUTING FORWARD THIS TRUTH WOULD BE COMPLACENCY!!!!

NDIGO: What is your goal as an artist?

TI -ROCK MOORE: I am resolved to speak of what most white Americans choose to ignore, and my hope is to bring into collective awareness the unpleasant truths of a system built on the foundation of white supremacy and white privilege. I believe we need to prioritize humanity in this country above all else, and then we will take one collective step forward.

By Hana Anderson