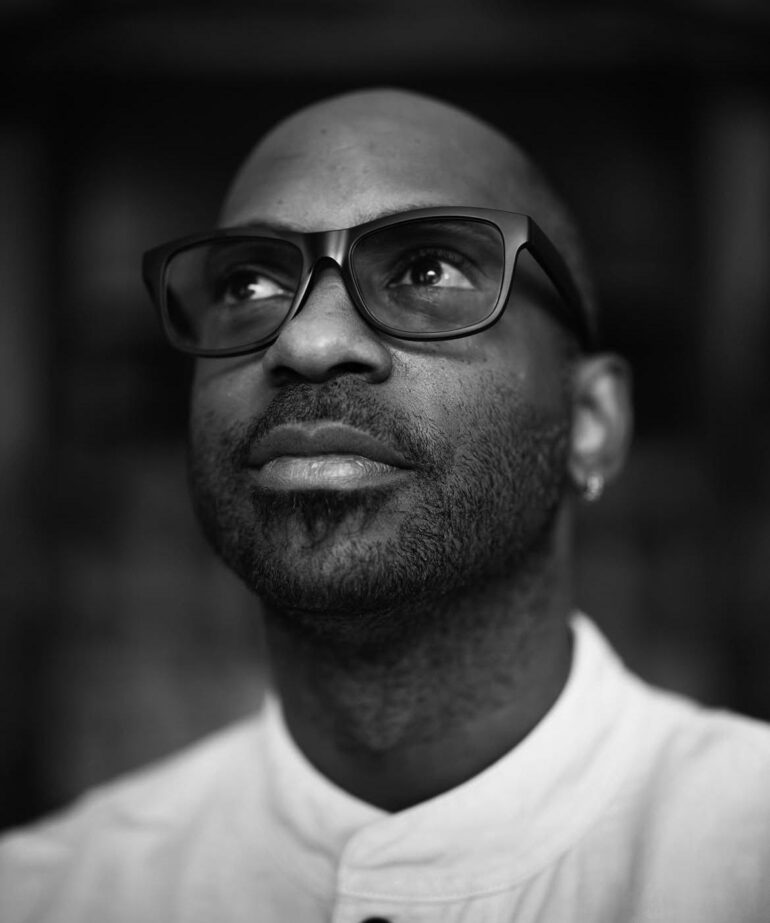

RaMell Ross’s Nickel Boys is a powerful cinematic exploration of the lives of young Black boys at the Nickel Academy, a real-life reform school in Florida known for its brutality. In this exclusive interview, Ross delves into the poetic nature of his filmmaking, the importance of Black love, and the transformative performances of his cast.

Reggie Ponder, The Reel Critic: You mentioned putting poetry into this project. Can you explain what you mean by that? Are you referring to the visuals, the writing, the music—or all of it?

RaMell Ross: I love that question because we throw poetry around like it’s an everyday thing, because it is. But there’s also different levels to it, different degrees, different nuances—it gets granular, macro, micro. When I think about poetry, I think it is the entire film project itself. Hopefully, it feels like a large poem, but even when you break it down to its constituent pieces, each of those feels like tiny stanzas. Each feels like language and words that are not used literally but as slight abstractions to give a person space to imagine within and think about the language itself. Poetry is supposed to strive—it’s supposed to be reductive and expansive and all these contradictory things at the same time.

From a writing perspective, how did you approach this as a poetic work?

If we think about the relationship between images and language—we know that language is a reduction of an image, right? The image is replete with symbols, signs, colors, and textures. A picture’s worth a thousand words, so they say. If we start with a script—and a script is going from language to image—it seems to me if you’re translating words to an image, then the image is servant to the words. But if you start with an image and then go to words, you’re approximating the power of the image with language and allowing for that image to be as expansive as our field of vision normally is. That’s one way I think about it: allowing images to breathe and not be beholden to narrative needs.

And what about the music? How did it contribute to this poetic vision?

I love working with Scott Alario and Alex Somers because those guys make music out of everyday sounds. They’re in their kitchens with tiny recorders or using their children’s tap-dancing class recording from 100 feet away and manipulating those sounds. What’s interesting is taking these handmade sounds and real-world sonic marks and associating them almost randomly in scenes to see how they intersect—like how a car horn, a car alarm, the screech of a tire, and someone screaming on the street turn into some sort of city symphony that’s familiar. It’s all made of discrete elements, but when they come together randomly, they feel like something real.

Poetry leaves room for interpretation. What were you hoping audiences would reflect on after watching this film?

I think I was trying to give the viewer an approximate experience of what it was like to look through the eyes of those characters during that time in a poetic way. Like I imagine looking through your eyes must be wildly poetic—what do you pay attention to? What sparks your attention? Bringing someone into an experiential space of Black identity where they’re having an aesthetic encounter as opposed to a narrative encounter—to me—is one of the grand aims: giving someone something genuinely sensory that leaves that indelible mark.

Speaking of themes—there’s also love in this film. Can you talk about how you portrayed different shades of love within the Black community?

I love that question because if you think about the history of cinema—as we watch what we think Black love looks like—one thing this film allows us to do is be in direct eye contact with that love. The love you got from your parents or your brother or grandma—for people outside the nuclear family in the Black community—is completely inaccessible for others. They don’t know what it looks like to be looked at with love from Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor as Hattie, from Brandon Wilson as Turner, or Ethan Herisse as Elwood. That eye contact is as piercing as it gets in the real world.

Let’s talk about Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor’s performance—it was so powerful! What stood out most?

Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor plays Hattie—and we know she’s special! She’s finally bubbling up where it’s undeniable she’s one of “the” greats. Aside from being the “love glue” of this film—I think she elevated all the actors; she gave each one lessons on how to embody their characters authentically.

What were you trying to capture about the Black experience?

I think this film is about what it, as much as possible – what it looks and feels like to be a young Black man of color in the 60s and the beautiful world that exists that one encounters while having something that’s irreconcilable with that beauty happening to you while you’re trying to survive.

Nickel Boys has already garnered critical acclaim, winning the Best Film Award from the African American Film Critics Association. The film will be released in Chicago on January 3, 2025.