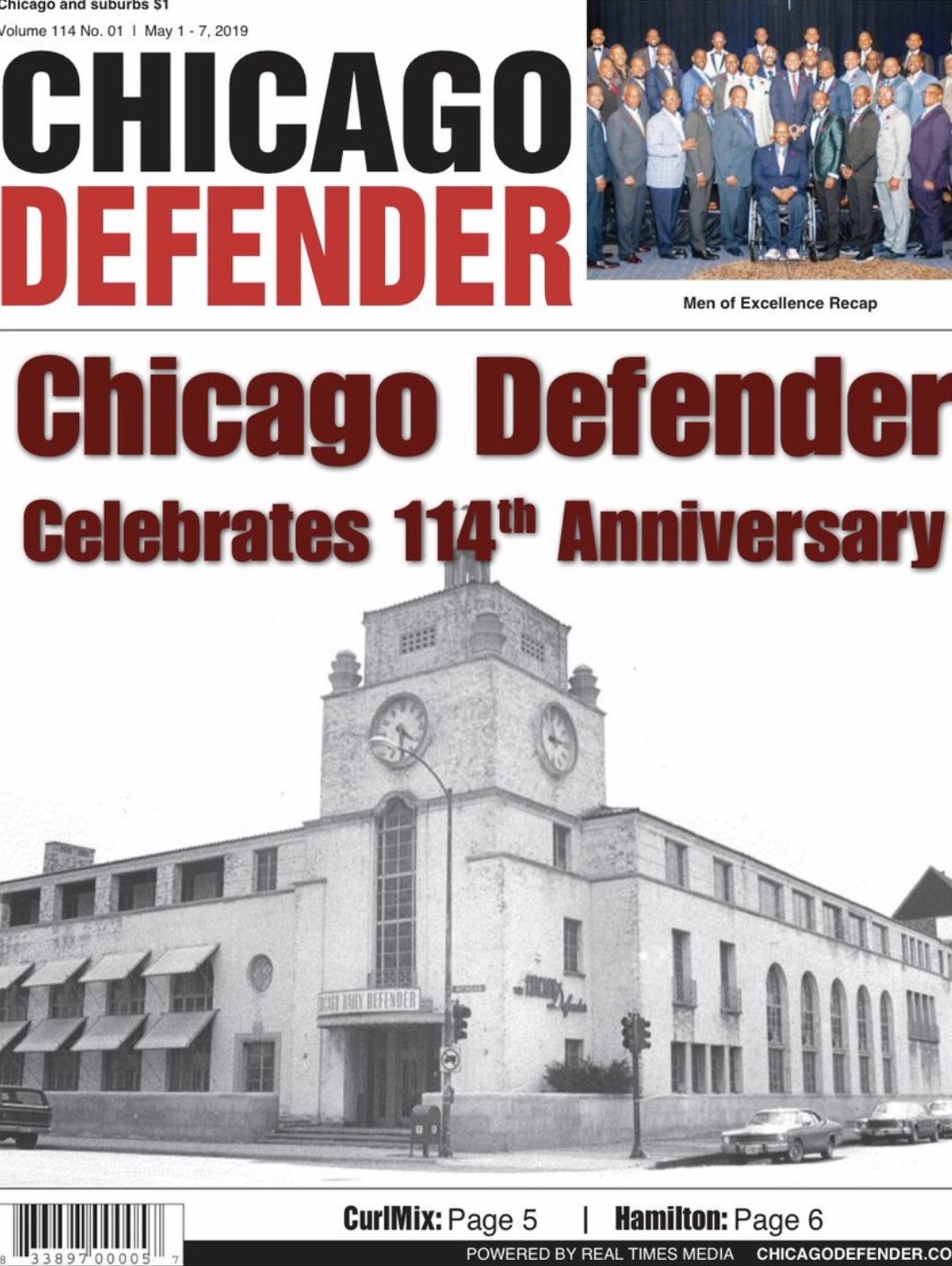

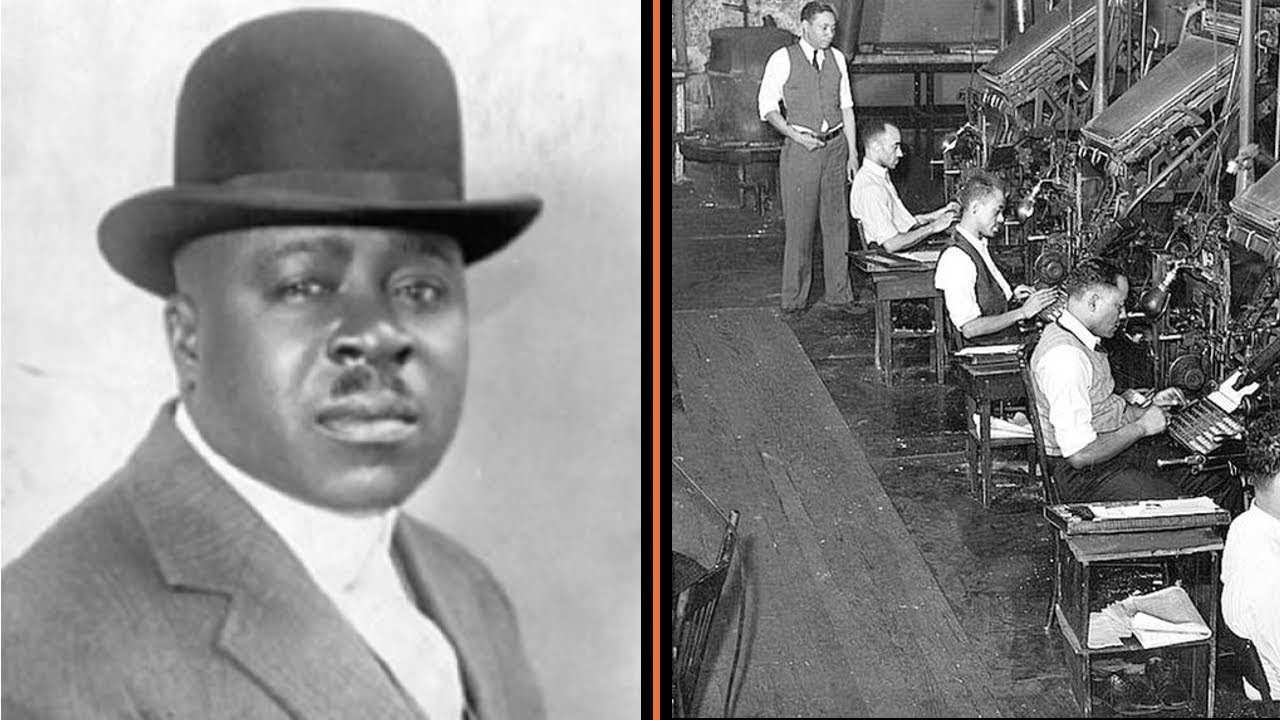

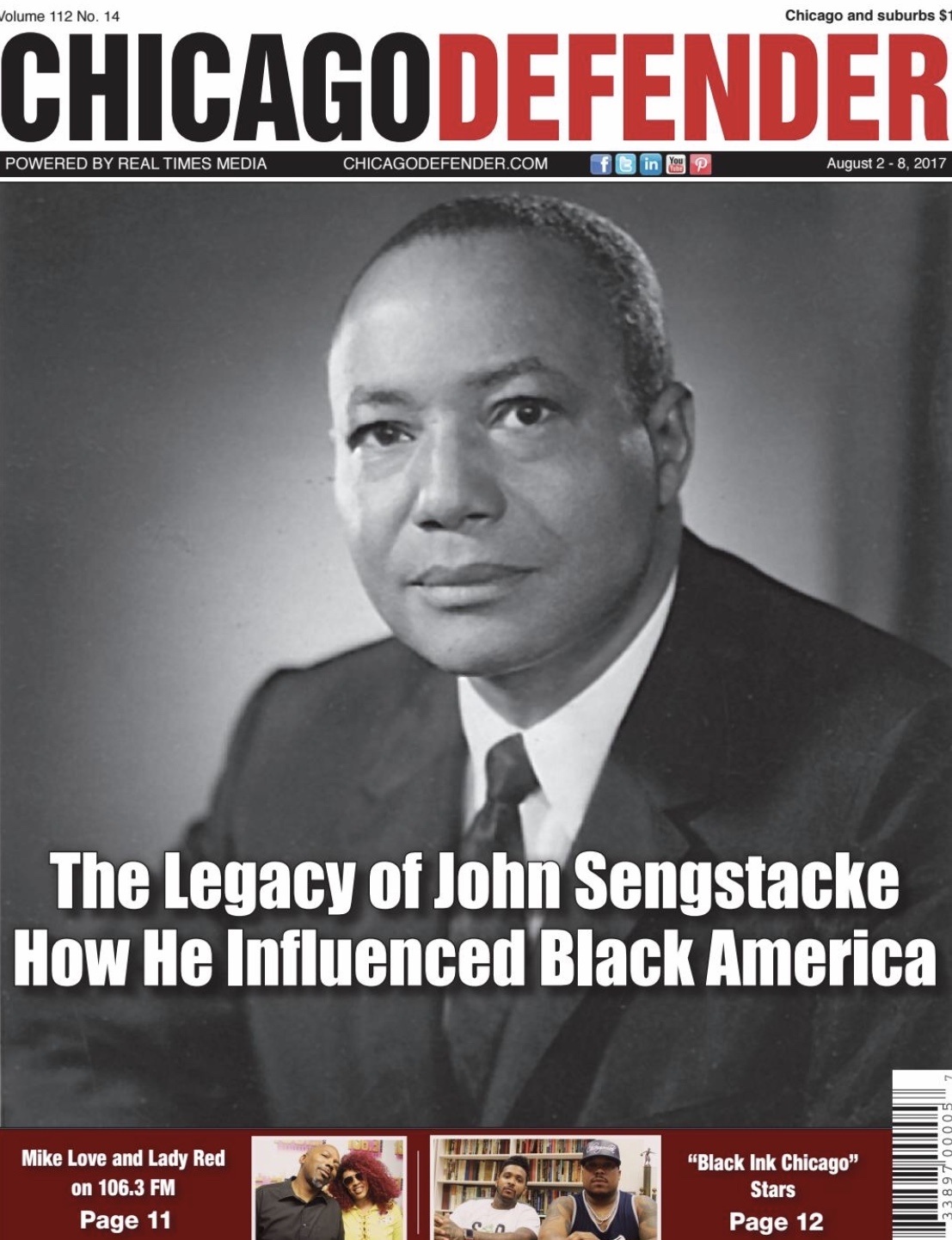

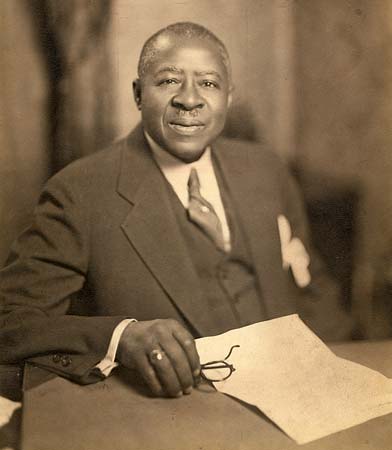

It was sad this past Saturday to read the front-page story in the Chicago Sun-Times about the Chicago Defender ceasing printing of its newspaper and publishing only digitally in the future. The 114-year-old Defender, founded in 1905 by Robert Sengstacke Abbott, prints its last edition this week.

It is a sign of the times, the times that clearly see newspapers across the country folding and the times that say the world has become digital. I often say America has been through a very quiet revolution – a digital revolution. Industry observers predict that in the next five years, major cities will have only one newspaper. I believe Chicago is headed that way.

The Defender has struggled for years since the death of its legendary publisher and editor, John Sengstacke, to stay alive and relevant. They moved from their landmark office building on 24th and Michigan, first to a corporate space downtown across from the Art Institute, and then to a smaller boutique space at 46th and King Drive.

They have had a host of publishers, some who were misfits at best. Newspapers require publishers; the publisher is the leader, the parent, the lover of the story, and the protector of the property. Publishers are lasting. They have struggled to stay relevant.

Almost all newspapers have moved their offices to smaller and probably cheaper quarters, including the Chicago Tribune, the Chicago Sun-Times and us at N’DIGO. In days of yesteryear, newspaper offices were spacious to keep archival papers and photos, for meeting spaces and for busy newsrooms.

The digital age has changed all of that. With computers, you certainly don’t need the space once required. Reporters and writers are at home or on the beach as they write and file stories. Publishers approve layouts, choose photos, and decide editorial. Publishers make the call on how many copies to print and have printing bills.

But digital technology has changed the dynamics of contemporary publishing. You possibly work with people that you never see, and pushing a button to send your editorial product to your audience online is cheaper than printed newspapers delivered by trucks to drop-off points for distribution. And where are the newsstands?

A Rich, Deep History

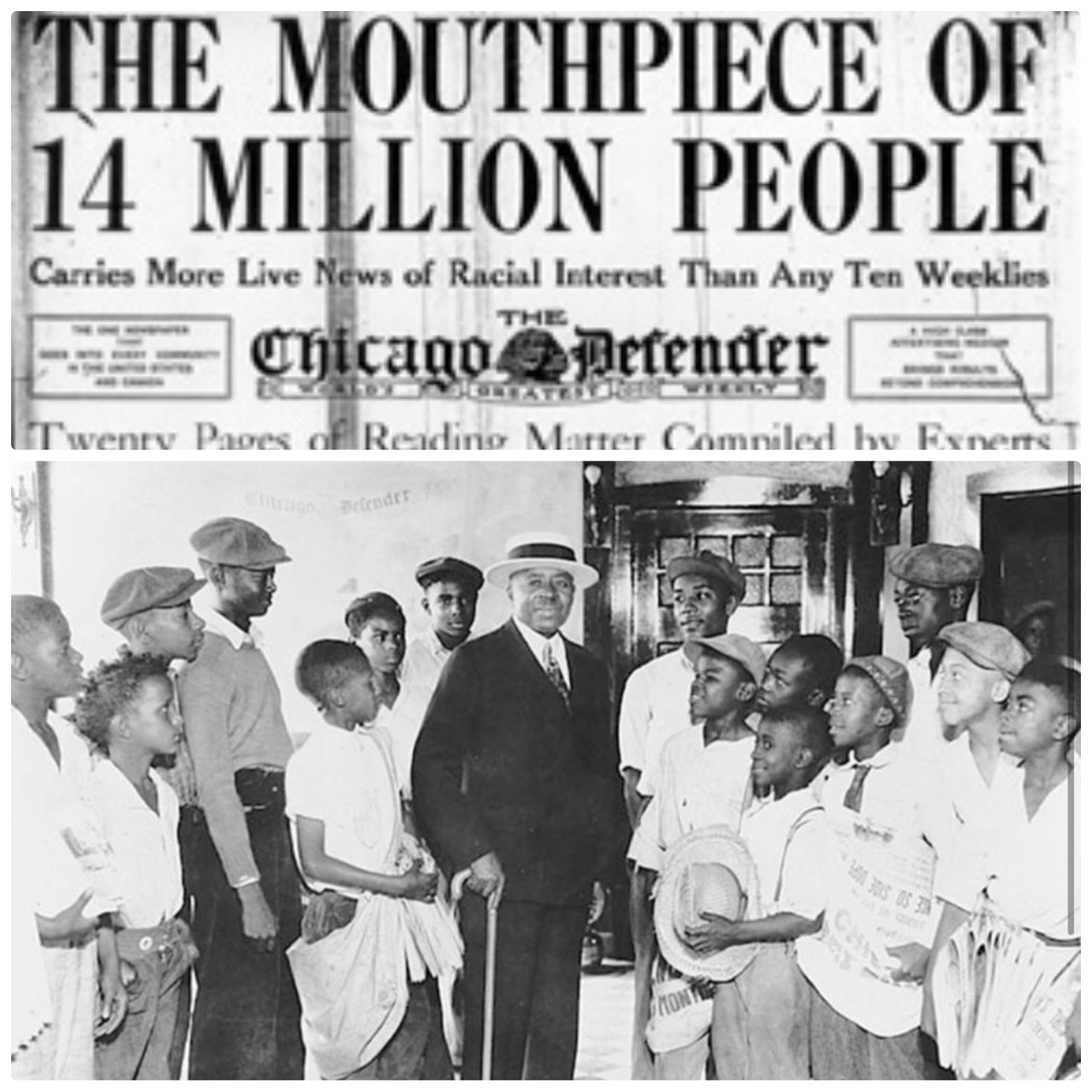

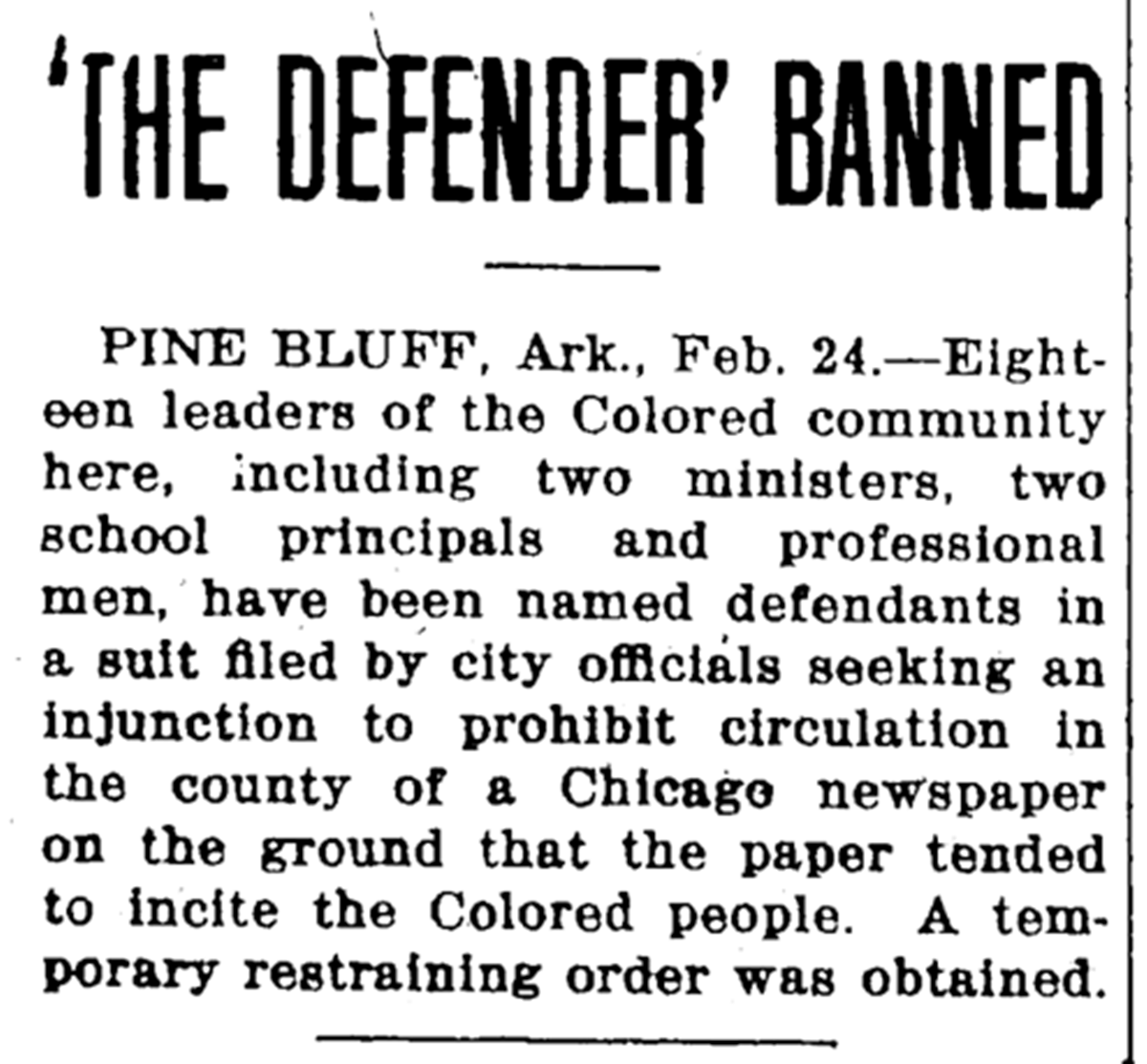

The Chicago Defender was an historic newspaper that assisted and steered the Great Black Migration from the South to the North via Pullman Porters, to the point that the “Great Migration” might not have been so great without the Defender.

Though Jet Magazine gets the historical credit for publishing Emmitt Till’s story in 1955 because of the iconic photo it ran that got national attention, it was actually a reporter at the Defender who broke the story. Her name was Mattie Smith Colin.

Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, called Mr. Sengstacke to meet her at the train station with Till’s body. Sengstacke thought it was best that a lady go to comfort Mrs.Till, so he sent Mrs. Colin. The major papers didn’t pay much attention to Black lives at that time.

The story of this Black Chicago teenager, who was lynched in Mississippi because he supposedly whistled at a white woman, might have been just an also-ran blurb in mainstream media had the Defender not covered it. Instead, the national publicity that came from the story was a key to galvanizing the Civil Rights Movement.

The Chicago Defender told the story of Black America and communicated directly to Black America, in turn humanizing Black America on the printed page. The paper told southern Blacks that there was a better life to be had in Chicago, the stockyard town, and other cities up North.

John Sengstacke spoke to United States presidents about baseball and recommended that Jackie Robinson integrate the game. He showed President Harry Truman the path to integrating the troops. He voice was loud and powerful.

The Defender made Black Chicago a leader in America, by talking about real issues in the country, by talking about politics in real time. You clearly had Black perspective that was respected – think Langston Hughes, Vernon Jarrett, Ethel Payne, Gwendolyn Brooks, Lu Palmer. There are many Black politicians who owe their elections to the Chicago Defender.

White ones, too, including President John F. Kennedy. His winning votes in his presidential election came from the South Side of Chicago. The Defender was so influential that its editorial director, journalist Louis Martin, was recruited to become a staff member at the Jack Kennedy White House.

The Defender in its heyday was the authentic Black voice in America on a host of topics, from entertainment to politics. To prove the point of Chicago being a tale of two cities, pick a date from yesteryear and read a mainstream paper and read the Defender and notice the difference in the coverage.

Now that’s all gone. But to put the demise of the print edition of the Chicago Defender in newspaper perspective, note that since 2004, 1,800 local newspapers of all stripes have shut down. On August 31, for instance, the 150-year-old Youngstown Vindicator, a daily newspaper in Ohio, will cease to print.

Now, what is happening in our city with the loss of Black media is the creation of a media desert. Where is the Black voice? A vacuum is created now that will miss viewpoint, insight, and real time news on Black life in Chicago.

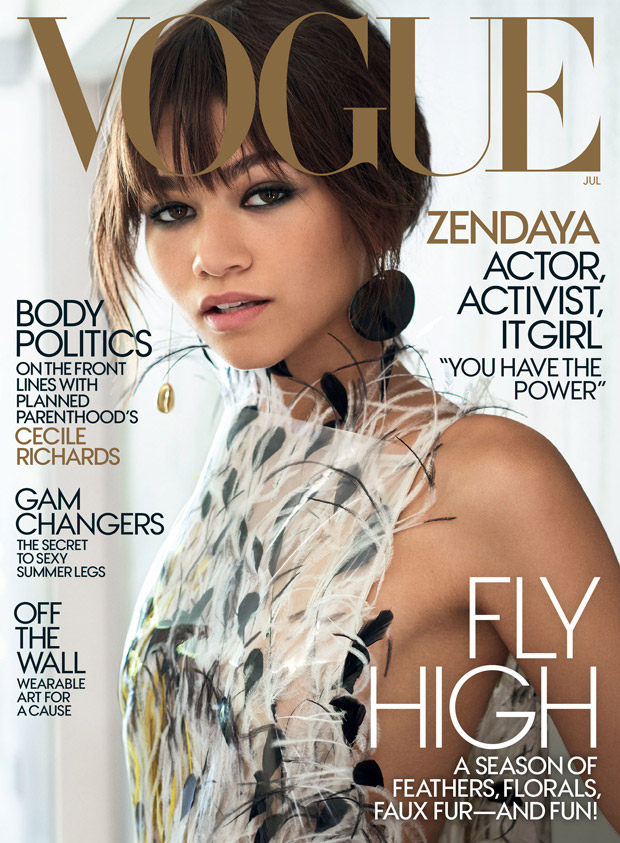

We experience it at the national level with the loss of Ebony and Jet Magazines, but somewhat, with Vogue and Elle and Vanity Fair suddenly being interested in Black personalities as cover stories, we see at least the appearance of Blackness.

But locally, Chicago is on its way to suffering a Black print media desert. The major newspapers – barely hanging on in their own right – still cover Black people marginally and missing, still, is viewpoint and perspective.

There are Black columnists who are free to write their opinions, but Black social events, emerging artists, institutions and the like receive limited to no coverage.

Instead, the mainstream media coverage is framed as Black folk in Chicago are violent; the (young) Black male is treacherous; Black neighborhoods are dangerous; and Black women issues don’t matter, if you let mainstream tell it.

Along Comes N’DIGO

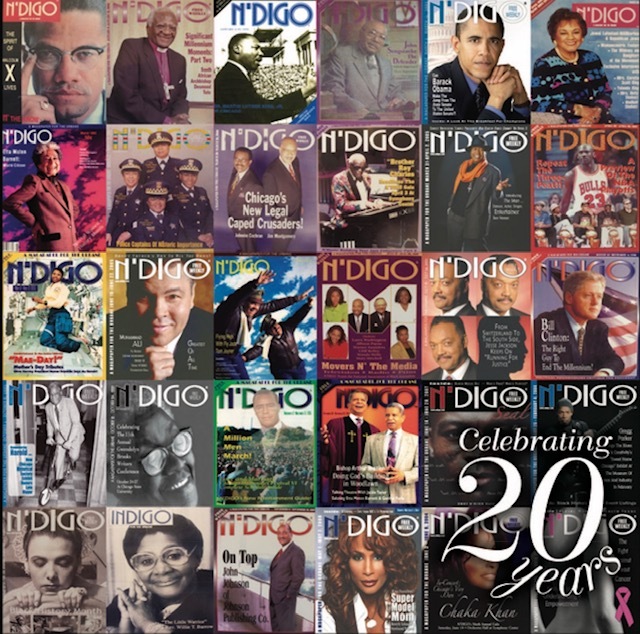

I started N’DIGO in 1989, as a reaction to both the Defender and mainstream. I thought it was time for new news, new images about Black folk. My friend, construction magnate Paul King, and I jointly wrote a lengthy factual article on what it would mean to Black Chicago if Mayor Eugene Sawyer lost the seat after Harold Washington died.

We wrote a tight story and presented it to mainstream media to print as an op-ed, but were told no, because this was not “their perspective”. In a bright and energetic, very innocent way, I took the same story to the Defender and they, too, rejected it.

Paul King suggested running the story as an ad that he would pay to print. We still got a “no”, with the words from the Defender being, “We have to stay alive.” They couldn’t afford to buck Chicago’s white political establishment by running the piece.

That was the real impetus for the birth of N’DIGO. My frustration and anger were high and Paul was in the background edging me on with business guidance and comfort. I said to King, “It’s a damn shame in this city, we have no modern paper with voice.” Paul said sharply, “Let’s start one.”

Today, where is Black media in Chicago, is a real question. We have two printed papers left of note – Dorothy Leavell’s almost 80-year-old Chicago Crusader, and the Citizen, founded in 1965 by the late Illinois Congressman Gus Savage and bought from him by the Bill Garth family in the late 1980s. Both papers have limited South Side distribution and online presence.

Death Of Print Advertising

There is still an audience for the printed word, mind you. That reader is older, economically stable, and reads the newspapers for viewpoint as well as news. You can see these readers in the barbershop, the beauty shop, the poolroom and the church. However, they don’t buy advertising, unfortunately.

Despite maybe having a paid circulation, newspapers, small and large, run on advertising. Newspapers are a business with two customers, the reader and the advertiser. Without advertising, newspapers are certain to perish. That is what all the newspapers in the country are experiencing today with the decline in print advertising.

As all the papers are fighting to survive, Black newspapers at every turn are disrespected by advertisers. In spite of having a Black customer readership base reflecting a trillion dollars of consumer buying power, Black papers are ignored, unless protests of potential advertisers are mounted.

Stores open in our neighborhoods and ignore the Black press in their marketing efforts. Politicians of every stripe running for office ignore the Black press as they seek Black votes, yet gather us collectively as they seek endorsement. Jewel Foods recently opened in Woodlawn, with much fanfare and not one Black ad. Jewel used to be a mainstay advertiser with Black press.

The recent Illinois governor’s campaign between JB Pritzker and Bruce Rauner saw record-breaking millions spent on media, but not a dollar in the Black press. Pritzker insulted the Crusader by trying to take out a $500 ad. The publisher declined it.

In the marathon Chicago mayoral race, candidate Willie Wilson made a real effort to spend with the Black press. He was the only one to recognize the Black press in his campaign marketing. In the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton’s campaign spent zero. Barack Obama, who has directly benefited heavily from Black press in Chicago, spent $10,000 nationally.

At the same time, Black businesses are poor advertisers; they usually want to make a deal which includes getting a major story for a very small ad buy. Sorry folks, but this is the reality.

Our public institutions like the City Colleges, Chicago Pubic Schools, the museums, the Park District, and the universities, who are all looking for Black students and Black visitors that they can’t find, ignore advertising in the Black press in their search.

A Changing World

There is no surprise that the Defender is going digital only. I hope this gives them a lift and that they attract a young, vibrant audience. It is a hard transition and it takes time, and it can happen if the content is timely. But the Defender online will never be what it was in print.

Ebony and Jet magazines went from print to digital only a few years back and now it appears that they may even lose their online presence shortly.

N’DIGO, with our front-page cover story with fabulous photo, is living exclusively online now. We are still hip and voguish, but it is different than holding that physical paper in your hand and framing the cover story and hanging it on your office or home wall, or sitting at the dining room table reading it with your family. I was so troubled by not being able to keep N’DIGO in print that I just went digital quietly without being able to publicly discuss it.

Black Chicago is in trouble as our media outlets change and cease. Our stories will be missed by mainstream and we will continue to be marginalized for accomplishments and achievements.

I hope Chicago foundations and the wealthy will step up and step in to save a dying industry that is very much needed. Chicago is still the city that works, with big broad shoulders, with big ideas and with historical political elections and fun events, but we will not be the same without the Defender. The printed version of the paper lasted 114 years – that’s a long run, with a rich history, and it is a miracle that it existed for so long.

Defender founder Robert Abbott’s mission remains to reflect on and tell the story of the Black experience, but from today forward, it will be done on a different platform. Chicago owes a debt to the Defender, to Mr. Abbott, and to Mr. John Sengstacke. Thank you for telling our story for over a century.

I cry and mourn and worry about journalism at large as it changes. I have lived long enough to see a viable industry die because of technological innovation; sadly, it is something that I never dreamed I would see happen in my lifetime.

Unless someone is saving digital content in the cloud or CD/flash drive, once the websites are revised, down or die, the digital content is gone forever inaccessible to future generations.

You are ever so right. What happens if digital becomes obsolete.