On Easter Sunday Eve, the world bid farewell to Pope Francis, a pontiff whose legacy will resonate far beyond the walls of the Vatican. His death on the cusp of Christianity’s most sacred celebration feels poetic, almost scriptural, as if he timed his exit with the symbolism he so often leaned into: death and resurrection, endings that give way to new beginnings. On his last day, he enjoyed Easter Sunday, praying and blessing others at the Vatican. He said he wanted to die with his boots on. He did.

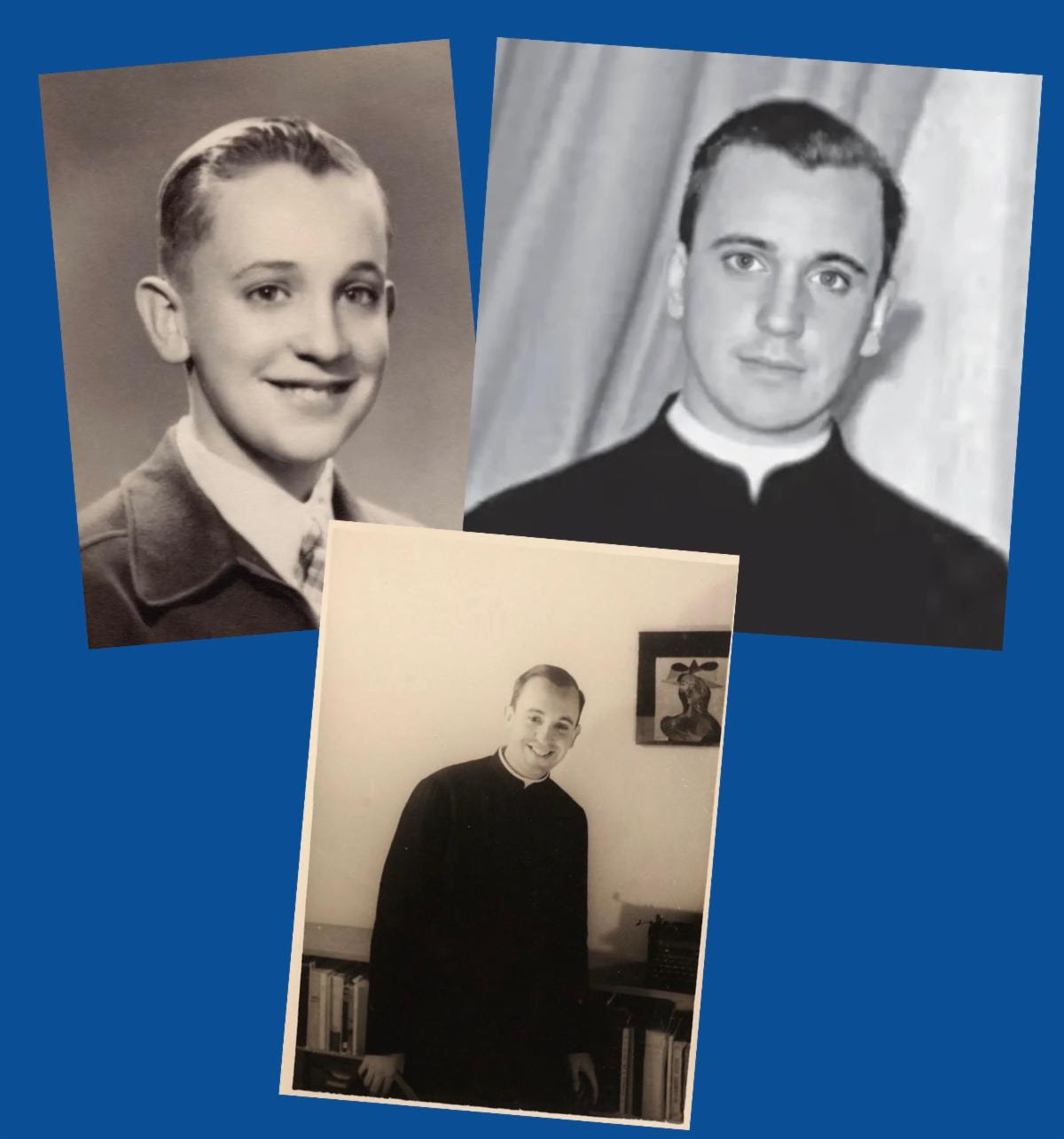

Born Jorge Mario Bergoglio in Buenos Aires, Francis was the first pope from the Americas, the first Jesuit to hold the office, and the first to take the name Francis — in honor of St. Francis of Assisi, champion of the poor and lover of peace. That choice was no accident. It defined his papacy from the outset: humble, focused on the marginalized, and boldly reformist. He lived in the guest house, not the Pope’s mansion. He argued the case for the immigrants, remembering his parents were immigrants.

History will remember Francis as a man who attempted to steer a 2,000-year-old institution through the turbulent waters of the 21st century. He sought not only to modernize the Church but also to soften its tone. His now-famous response to a question about gay priests — “Who am I to judge?”—symbolized a departure from doctrinal rigidity and a turn toward pastoral compassion.

Under his watch, the Vatican took unprecedented steps toward transparency in its finances, tackled long-standing issues of clerical sexual abuse (albeit not without criticism and resistance), and opened doors to conversations about celibacy, women’s roles in the Church, and interfaith dialogue. He did not solve every crisis, but he acknowledged them — and in doing so, changed the tenor of papal leadership.

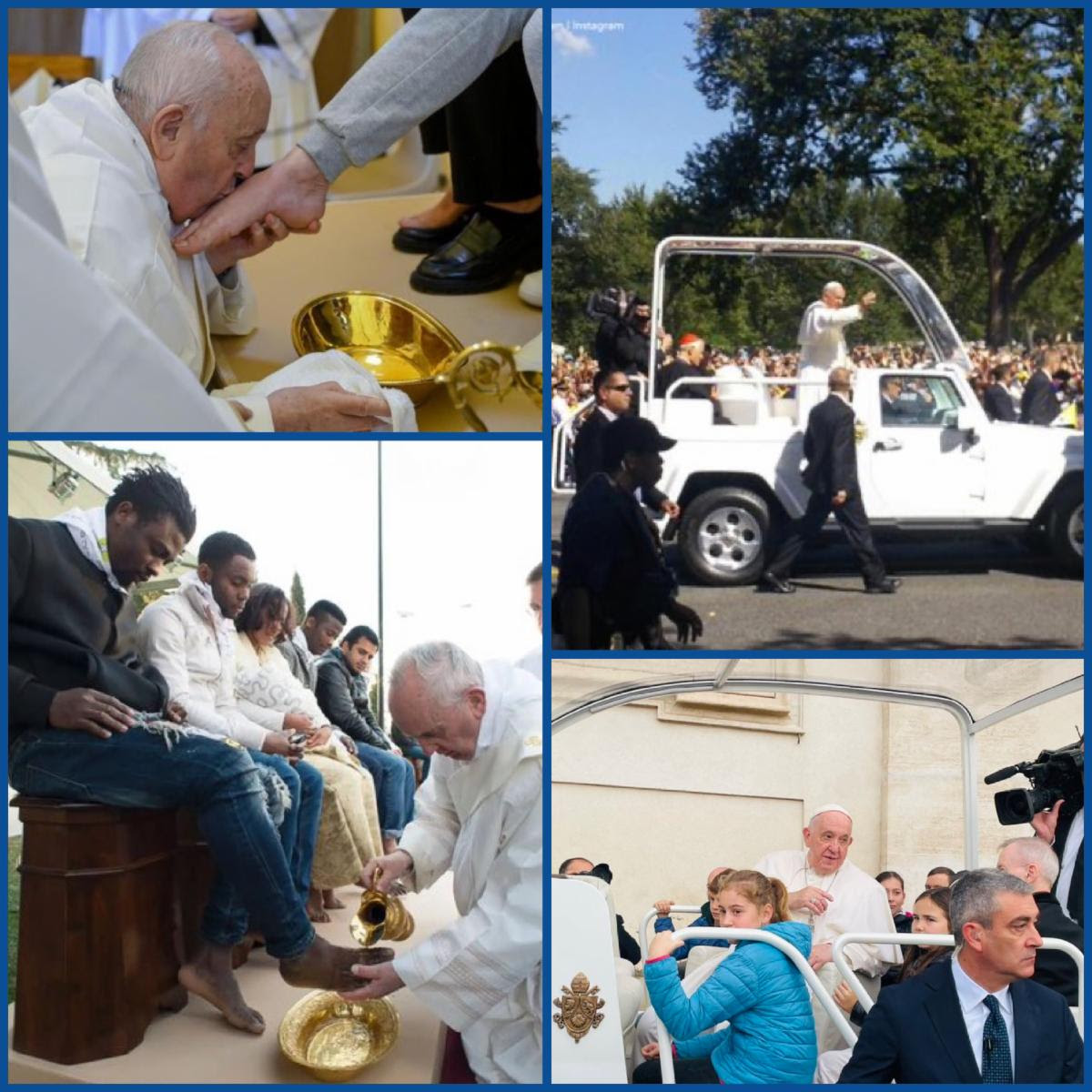

Francis was a spiritual grandfather to the faithful — warm, direct, and deeply human. He rode in a modest Fiat instead of a limousine. He rode in an Jeep Wrangler with an open top, not the “sardine” car, where he was closed off. He washed the feet of prisoners, immigrants, and women. He embraced the disabled, comforted victims, and wasn’t afraid to look visibly shaken by the pain he witnessed. To many, he brought the papacy down from a gilded throne and into the streets.

But not all agreed with his approach. His critics, inside and outside the Church, viewed him as too political, too progressive, or not progressive enough. He walked a fine line, often stretching the boundaries of tradition without breaking them, choosing dialogue over decrees. History will likely see this as his strength and constraint — the mark of a man trying to build bridges without burning the past.

Pope Francis may be remembered most for his relentless message of mercy. In a world fractured by division, climate crisis, migration upheaval, and spiritual hunger, he dared to speak in the language of love and forgiveness. He reminded us, again and again, that the Church should be a “field hospital after battle,” not a courtroom.

As bells toll in mourning, they also ring in gratitude — for a life lived in service to others, a pope who believed in the power of humility, and a man who never stopped pointing toward hope, even in his final hour. History will remember Pope Francis not just for what he did, but for how he made people feel seen, heard, and held.

May he rest in peace, and may his legacy live on in acts of compassion across the globe. May we all be blessed for his service to the world.