There is a move afoot to ban books and suppress stories that deal with race.

Education writer Julie West Johnson called out this alarming trend in a recent issue of Chicago Life Magazine. “The moral panic we’re seeing has created an extraordinary environment,” she observes. “Many of the books being challenged these days have been sitting on library shelves for years without comment. Some books are now under attack because they tell the truth about American History or explain race and politics in the past or present.”

Consider the efforts of Matt Krause, a Texas Republican and state legislator who seeks to oust some 850 books from school libraries and curricula that could give White students “discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress.” A school district in San Antonio has already pulled 414 books from its libraries and classrooms, responding to growing pressure from lawmakers and from “a vocal segment of angry parents.”

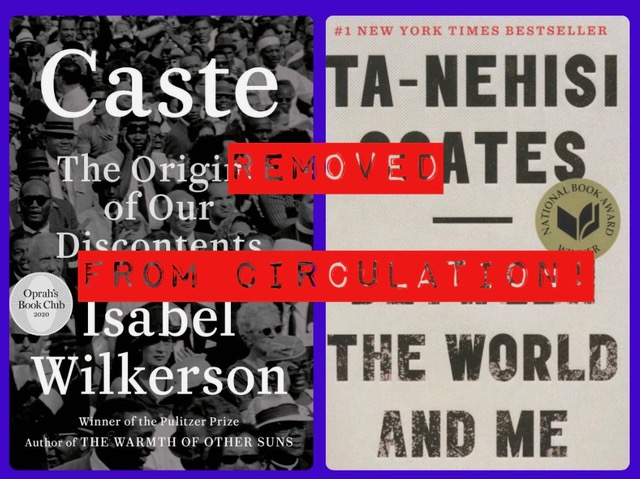

Among books the district removed from circulation was Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, The Origins of Our Discontents, which looks closely at the history of slavery and racism in America. Same with Ta-Nehisi Coates’ National Book Award winner Between the World and Me, in which the writer speaks honestly to his son about his experience as a Black man in America. I have had in-person conversations with Black authors and treasure signed copies of their books.

This Gets Personal…

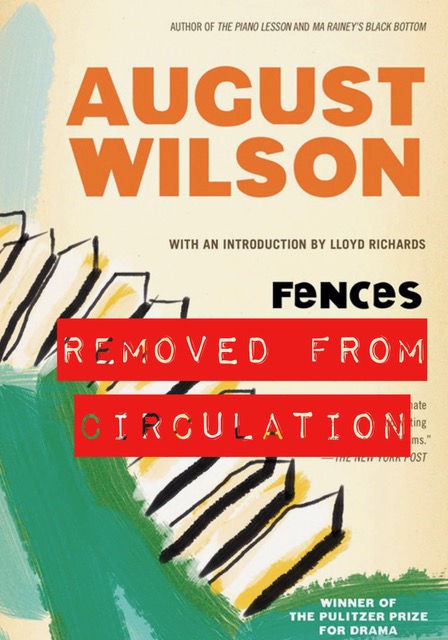

The travesty that really got me going, however, was reading about a Wichita, KS school district’s decision to include Black poet and playwright August Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Fences on their list of 29 books to be removed from school libraries. This was a gut punch. This made it personal.

This past winter thousands of Chicagoans got to marvel at the genius of Wilson when his play Gem of the Ocean returned to the Goodman Theatre, where his masterpiece premiered in 2003.

“GCM” is one of ten interconnected plays documenting the culture, history, and lived experiences of African Americans from slave days to the present. It is this writer’s opinion that these plays are a must-read-and-study body of literature. Wilson considers each decade of the 20th Century, with Gem of the Ocean set as the earliest in 1904. My wife Loann and I were privileged to see this play at the invitation of Goodman Resident Director Chuck Smith during its premiere run in 2003. We saw it again this past January. The earlier performance included dinner with the playwright, giving us a chance to exchange ideas on his motivation and creativity.

“I wanted to place this (Black) culture on stage in all its richness and fullness,” he was later quoted as saying, “and to demonstrate its ability to sustain us all in areas of human life and endeavor and thought.” There have been, he added, “profound movements of our history in which the larger society has thought less of us than we have thought of ourselves.”

The kicker to all the above was being invited recently to stream a live performance of Gem on our home big screen TV. This was made possible by the Goodman, and it was terrific! You could pause it, repeat it and see the tension in the faces of the performing artists.

Wilson shows us that, not only is it alright to be different from mainstream White America but these differences must be celebrated rather than repressed. He is troubled by the unspoken desire among too many African Americans to distance themselves from their slave ancestors as if that part of their history did not exist.

Drama scholar Sandra Shannon, in her book The Dramatic Vision of August Wilson, points out that “Conversely he envies those people who are not ashamed today to keep traditions such as dancing the polka or celebrating Passover and he (Wilson) finds it painful to consider the campaign by Jews to keep memories of the Holocaust fresh in the minds of their people while far too many African Americans seem embarrassed by any African linkage.”

City of Recovered Memory…

Africa plays a vital role in Wilson’s work. He takes us to Africa, either by incorporating some visually familiar reference or, in some instances, by invoking supernatural or mystic phenomena. The segment City of Bones in Gem of the Ocean is a perfect example of this.

The City of Bones is the mystical city in the Atlantic Ocean that was built by the bones of Africans who died aboard slave ships bound for the Americas; their corpses were thrown overboard like spoiled meat.

There’s Citizen Barlow, a young Black man, who comes to a house to be cleansed by Aunt Ester. Ester is the 285-year-old – no typo! – the matriarch of the family. Barlow is the seeker and confessant of the play. A migrant from Alabama, he wants to work in a factory, but he steals a bucket of nails, which results in an innocent man drowning rather than submit to an arrest for a crime he did not commit. He insists on seeing Aunt Ester to confess his sin of Black-on-Black betrayal. His mother named him Citizen “after freedom come.” But Solly Two Kings reminds him that truly to be a “citizen” he’ll need to fight to uphold freedom even when it becomes a heavy load.

Solly Two Kings is a 67-year-old former slave and a conductor on the Underground Railroad. Aunt Ester is also a former slave who is the keeper of tradition and history. She guides Citizen on a lyrical journey of spiritual awakening aboard the legendary ship Gem of the Ocean to the City of Bones. While on the excursion, Citizen comes to understand the story of his ancestors and faces the truth about his crime and the innocent man he wronged.

The dialogue between characters is nothing short of symphonic! It swells between Black Mary and her policeman brother, Caesar Wilks. Also, between Aunt Ester and Solly Two Kings. Director Chuck Smith posits that these two had a love affair in motion. On this City of Bones trip, Citizen is surrounded by Solly, Black Mary, Eli, and Aunt Ester. It is a communal and spiritual masterpiece. As the play evolves, Citizen inherits the deceased Solly’s walking stick, and Black Mary gets Aunt Ester’s shawl symbolizing the generational transfer of power and purpose. The transcendent, mystical travel to the City of Bones, said Smith, is always an adventure.

Inheritance Lost and Found…

Moreover, it is an adventure with direct ramifications for Black Americans here in the 21st Century. Understanding our past is essential to navigating our future. In the face of the horrors of slavery and Jim Crow, Black people employed sermons, prayers, and gospel songs to survive, steel our determination, and succeed. This cultural vitality and continuity can be found in the Blues, Jazz, and Negro spirituals.

Embracing this heritage is also what the late Zora Neale Hurston counsels in her masterpiece Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo.” She influenced playwright Wilson. They appear to be cut from the same cloth in many ways, even though they were decades apart.

Writing in their introduction of a new reissue of Hurston’s essays You Don’t Know Us Negroes, Henry Louis Gates and Genevieve West speculate on the influence Zora would have had on August.”History has borne out Hurston’s prediction (that) in the works of so many of her literary heirs, male as well as female, who, taken together since Hurston’s literary recovery, have produced perhaps the richest field of fiction in the literary tradition, all indebted one way or another to the poetics and the practices of Zora Neale Hurston.”

Gates and West, a Hurston scholar, continue on the kinship between Wilson and Hurston. “Because of the boldness of her aesthetic theory and the novelty of her political critique, white and Black folks have been ‘overhearing’ the resplendent voices of the Black experience, within the veil, in a wide variety of ways, of which Hurston no doubt would approve.

Here’s Zora Neale Hurston’s in her maestro piece Barracoon, which centers around Cudjo Lewis, one of the last living freed slaves to be interviewed by the persistent writer. She brings the full focus on something many of us would choose to avoid. To wit: African chiefs SOLD defeated and captured Africans to White slavers.

As Alice Walker writes in the forward of Barracoon “Who could face this vision of the violently cruel behavior of the brethren – and the sisters? Who would want to know, via blow-by-blow account, how African chiefs deliberately set out to capture Africans from neighboring tribes, to provide wars of conquest in order to capture for the slave trade people — men, women, children – who belong to Africa? And to do this in so hideous a fashion that reading about it 200 years later brings waves of horror and distress?”

What Cudjo Remembered…

Cudjo Lewis provides Hurston with a perspective seldom voiced. How Black people came to America, and how they were treated by Blacks and Whites who greeted them. How Black Americans who were themselves, enslaved people, ridiculed the Africans, making their lives so much harder. Then there is Cudjo’s life after Emancipation. His happiness with his newfound freedom helped create a community and build his own house. It’s great. But how does one who has become homeless and unemployed fare? Not an unusual question in today’s America, but when the person was recently a slave, it’s different.

In his book The Last Slave Ship, Ben Raines also talks of Cudjo. He is a victim of the African Kingdom of Dahomey, one of the most brutal slaving regions in world history. In Africa, a 19-year-old Yoruba named Kossula, Cudjo, came not with a passport but with a slave ticket. Hurston interviewed him when he was 87-years-old. The community Kossula founded in Alabama was called Africatown. Kossula was not just a knowledgeable Black tapped for a few stories, tales, and colorful phrases, and Zora Neale Huston knew this. She did not perceive Baracooon as another cultural artifact illustrating the theoretical characteristic of Negro expression but as a singular portrait of Black humanity.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, in his book Between the World and Me, writes he “is a specific particular, a specific woman or man. Kossula, his wife Abile, and their six children, the host of Africans who founded Africa town, and their shipmates who survived the Clotilda (the slave ship they traveled on).

None other than James Baldwin, in his White Man’s Guilt, offers that this history – Cudjo’s history – is “Literally present in all that we do, and the power of history, when we are unconscious of it, is tyrannical acts. Barracoon is a counter-narrative that invites us to break our collective silence about slaves and slavery, about slaveholders and the American Dream.”

Why We Fight Censorship…

This is why those banned books matter. Benighted politicians, whether in Texas, Kansas, or even the Land of Lincoln, must not be allowed to decide what our children can and cannot read.

Writers like August Wilson do not so much assail the wrongs of the past as they bring them into focus and show how past African Americans addressed them and rose above them. Wilson and his literary forbears challenge today’s African Americans to see themselves participating in a historical dialect that shows how best to avoid the mistakes of previous generations. They are a means of communicating and empowering despite seemingly insurmountable odds.

Black writers do not so much portray Blacks as victims of racism, although their circumstances often and accurately appear otherwise – but as capable men and women who, by grasping and valuing our history, will stop wasting rhetoric and energy reacting to unfulfilled lives and missed opportunities and start believing in themselves.

Action Items…

After teasing you with a taste of August and Zora, take a nourishing dive into these Black geniuses:

*Contact Goodman Theatre’s Resident Director Chuck Smith can be contacted via Victoria Rodriquez at Victoriarodriquez@goodmantheatre.org. The Goodman hosts various events on Wilson’s Work. Check with Victoria.

*Watch the introduction to Gem of the Ocean by Dennis G. Jerz https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=paVFOW9PuL8

*Gem of the Ocean- Full play video. (online access)

*Zora Neale Hurston can be “googled” using such keywords as Their Eyes Were Watching God (2005); The Gilded Six Bits, the 2001 film by Booker T. Mattison; Barracoon; and Zora Neale Hurston – You Don’t Know Us Negroes and Other Essays with an introduction by Henry Louis Gates and Genevieve West; and at https://wfpp.columbia.edu/pioneer/zora-neale-hurston/

Finally, August Wilson and Zora Neale Hurston have made us an offer we cannot refuse. Give ’em a shot! And don’t let anyone tell you their works do not belong in our schools, in our libraries … and in our hearts.

Paul King, Jr. is a construction consultant and member of Chicago’s Business Leadership Council.

Paul King, Jr. is a construction consultant and member of Chicago’s Business Leadership Council.