When the video of Derek Chauvin’s knee firmly – and ultimately fatally — planted on the neck of George Floyd went viral, the image unleashed a global outrage. The brazenness of the act and the now-convicted Chauvin’s obliviousness to the heinousness of it were both repulsive and galvanizing. Through a continuous loop, the world saw —over and over and over – Floyd’s life being snuffed out as he pleaded for air and for mercy. And, in a howl that provoked both anger and compassion, Floyd even cried out to his late mother.

In unity, disparate groups from all races, ethnicities, persuasions, and different agitating levels marched, took to the streets, pumped their fists, and cried out in a show of collective anger. That fury resonated from every corner of the globe. It was an in-your-face symbol of the injustice heaped upon African Americans. It was made even more suffocating because the media captured every move.

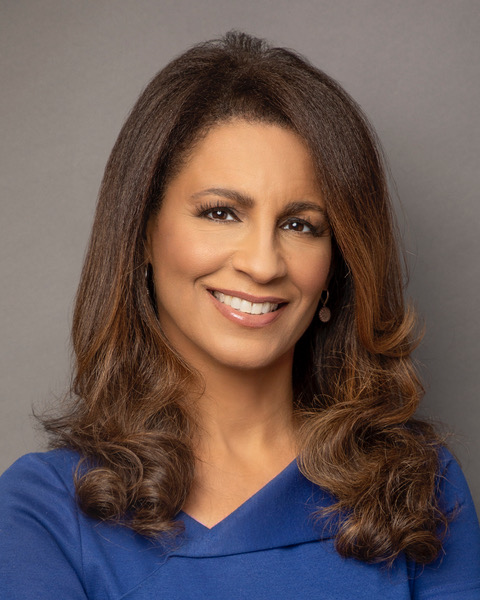

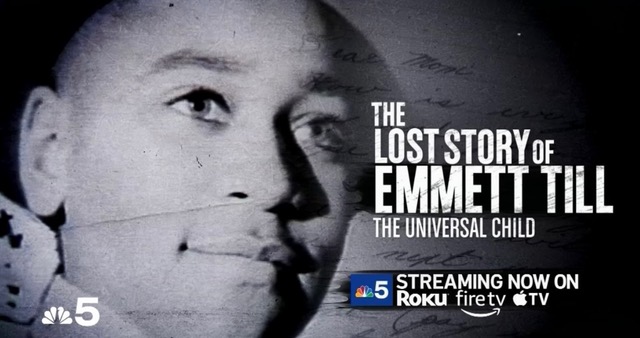

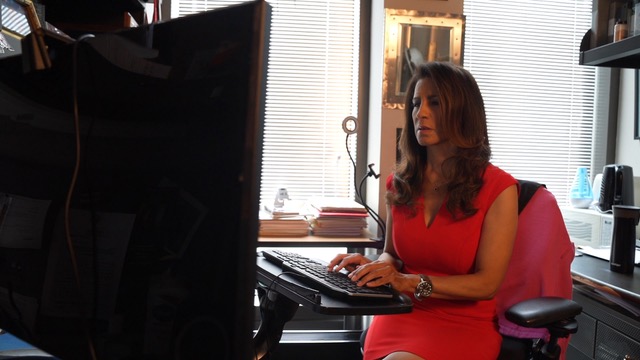

But this horrific image is not without precedent. A forerunner to this is equally and arguably more chilling: the vicious murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955 in Mississippi. And yet, it is a story often lost to history. But it is a saga that NBC5 Chicago – under the deft direction, passion, and leadership of anchor, an award-winning reporter, and investigative journalist Marion Brooks — deemed worthy of retelling. It is captured in the original documentary The Lost Story of Emmett Till: The Universal Child. Brooks helmed and choreographed every aspect of the documentary. This story, which Brooks hosts and narrates, is a documentary of NBCChicago.com and can be viewed on Roku, Amazon Fire, and Apple TV streaming platforms.

In bringing the story back to the public eye, Brooks captures the background, the serendipitous set of circumstances surrounding the tragedy as well as the cruel underbelly of the times that created the lynching.

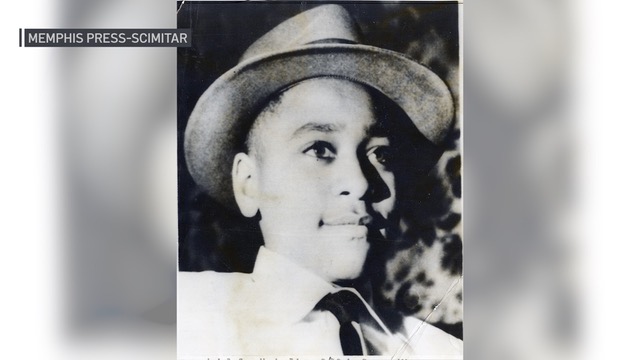

As recounted in the documentary, the chain of events that led to this tragedy began when Till’s cousins readied for their annual summer pilgrimage to Mississippi where they visited relatives. Emmett, an “innocent” 14-year-old only child living with his mother Mamie Till Mobley in a middle-class haven in Chicago, wanted to join his cousins, Wheeler Parker and Simeon Wright. Mamie had raised Emmett in a cloistered environment where he was on a successful path. But Mamie knew that the free-spirited Emmett had been shielded from the violence and palpable hate that defined Mississippi. She refused to grant permission. With Emmett intensifying his pleas, Mamie finally relented. Recognizing that hate toward Blacks put the happy-go-lucky Emmett in peril, she paced him through the dangers lurking in Mississippi. Despite the talk, she remained anxious. Nonetheless, with his cousins, he was off to Mississippi in August 1955.

The extent to which Emmett absorbed his mother’s warning was tested within a week of arriving in Mississippi. He and his cousins went to nearby Bryant’s Grocery & Meat Market in Money, Mississippi. While there is an amalgam of interpretations that recount the event, the oft-repeated version is that Emmett went against the warnings and admonitions that his mother had cautioned him about and he wolf-whistled at Carolyn Bryant, wife of the owner. Aware of the potentially deadly consequences of such an action, the boys high-tailed it out of the area. In blind fear, they even took a running detour through cotton fields when they sensed danger. But that turned out to be unwarranted. Once safe, the cousins bore down on Emmett for his deathworthy act. That instilled fear in him.

When days passed with no retaliation, the boy’s fears eased.

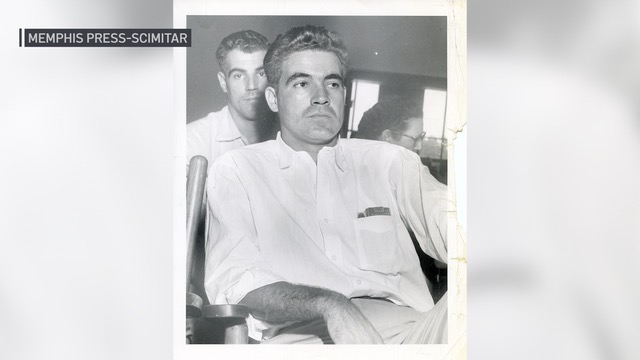

But that was a short-lived sense of relief as on the morning of August 28, 1955, Carolyn’s husband Roy Bryant and his brother-in-law J.W. Milam, rousted Emmett out of bed and kidnapped him — to the horror of the cousins. Three days later, his body was found dumped in the Tallahatchie River. He had been tethered to a cotton gin fan attached to barbed wire, making the corpse less buoyant and less likely to float to the surface. But one leg was spotted by a teenage fisherman. Upon summoning the law and examining further, it was determined to be a body. A gift of a ring from his late father that was inscribed with his dad’s name was the lone item that identified Emmett Till. The body had endured extreme trauma and torture. His eyes had been gouged out and he’d been shot. The body’s condition from the water and from the advanced state of decomposition made it unrecognizable.

Local law enforcement wanted to hurriedly bury the “remains” on-site as part of a ruse to cover up the crime. But that was torpedoed when Mamie Till Mobley landed in Mississippi. She took ownership of the mangled body and had it shipped to Chicago. Rather than have the body embalmed and restored to some viewable semblance, Mamie made the conscious choice to have the remains displayed in an open casket. In showing the body “as is,” Mamie graphically exposed to the world the egregious, awful mutilation and the barbaric consequences of racism and injustice. The monster of hate was embodied in his mangled body.

Lines snaked around the corner of the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ as over 100,000 viewed the bloated and contorted remains – many overcome with emotion. Simeon Booker of Jet Magazine covered the funeral. With him in tow was photographer David Jackson, who, with Mamie’s blessing, took the iconic photo of Till in the coffin. This hard-to-watch-but-can’t-turn-away photo was the flashpoint. And the issue of Jet that featured the horror saw record-setting sales and reprint runs including internationally. It also graced the pages of the Chicago Defender. Like the loop of Floyd’s life being snuffed away under a knee, the photos put a spotlight on injustices against Blacks and helped galvanize the civil rights movement.

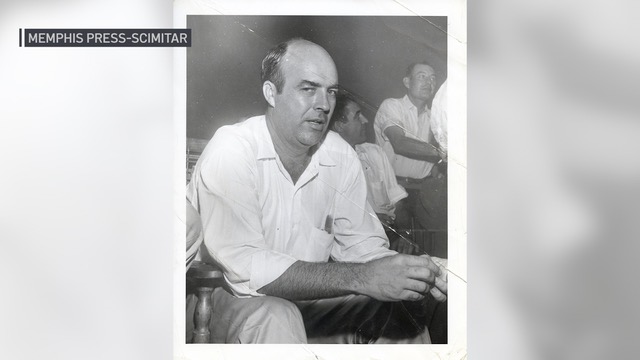

Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam were indicted and arrested on kidnapping charges. Twenty-two days later, they stood trial.

The atmosphere in the Tallahatchie County Courthouse was tense with Blacks calling it “terrifying.” Even the brave Mamie Till Mobley decried entering the courthouse as a matter of “getting in and out alive.” The cousins’ courage in accounting the night Till got kidnapped and the surprise and brave testimony of 18-year-old Willie Reed were climactic moments. They put their fears of retaliation behind them, in open court, where onlookers and the media were segregated. In a show of heroism, they pointed to and identified the offenders. But a conviction was not the outcome from the all-white/all-male jury. The verdict was “not guilty.” The entire trial was denounced even among the international press. The Paris-based American Jewish Committee conducted a survey of the American press and issued a “total and unqualified condemnation of the court proceedings.” Months later, the “killers” spewed their story to Look Magazine’s, William Bradford Huie. While admitting their guilt even against their manufactured version of the events, there was zero chance of them being retried because of double jeopardy. So, in the end, there were no consequences.

The saga haunted Marion Brooks. Seeing the George Floyd/Emmett Till parallels, Brooks was committed to keeping Till’s story alive. In this give-and-take with N’DIGO, she chronicles her deep dive into the story. She recounts Emmett Till’s journey as an innocent and carefree 14-year old to the unimaginably brutal lynching that elevated him to martyr status. Brooks describes the environment in Mississippi that oozed hate toward Blacks. She reflects on Mamie’s undaunting spirit and will and how she and Emmett inspired the civil rights movement. In the piece, Emmett is hailed as the Universal Child – a name that spawned the title: The Lost Story of Emmett Till: The Universal Child.

The piece aligns with Brooks’ resolve to educate and provide context to an era – a moment if you will — – that produced this ghastly murder.

N’DIGO: Marion, I enjoyed The Lost Story of Emmett Till: The Universal Child. It’s very raw and real. But I’m curious about the process that led to this being added to NBC’s streaming service. How did this get a green light? Take me into the room where the decision was made.

Marion Brooks: Well, the idea came on my radar in August 2020, which marked the 65th anniversary of Emmett Till’s kidnapping and murder. There was a commemorative event at Burr Oak Cemetery where Till is buried. Rev. Wheeler Parker, Till’s cousin – who was there the night Emmett Till was kidnapped – hosted the event. I didn’t attend, but I saw the video from it, and they pulled file photos. It’s the first time I learned that Rich Samuels, a former reporter at the station, had done a story on Till in 1985. He wrote the piece, and the late Anna Vassar produced it. They did a fantastic job, and Wheeler praised him effusively and generously. Rich interviewed so many people who are no longer here and even boldly confronted one of the killers trying – unsuccessfully – to get him to talk. And I thought, “We need to revisit this story and bring it to today and back into our consciousness.” That was my idea. I conceived it. I wrote it. I researched it. I did all of the interviews. I created it. I had a choice of doing a documentary or a TV story. The Roku channel is our streaming channel, and we could do a longer story there. So I pitched it to the digital team. They were all in and all over it. We incorporated some of Samuels’ 1985 footage into this documentary.

What is it about this saga that intrigues you?

This is an important story, and people need to be aware of it. I didn’t know it had fallen out of the public eye. That is my area of reporting. I’m drawn to social and criminal justice. I like taking a deeper dive. The Devil’s in the details, and the nuances are in the minutiae. It’s critical for people to understand what America was like in 1955.

What is its purpose…its mission?

The mission is always to educate. Always. Always. Always. History does fall away if you don’t keep bringing it out. I’m really big about context against the background of what was going on at that time. People have their own perceptions, but context helps to paint the whole picture. Ultimately, the role of a journalist is to educate and inform.

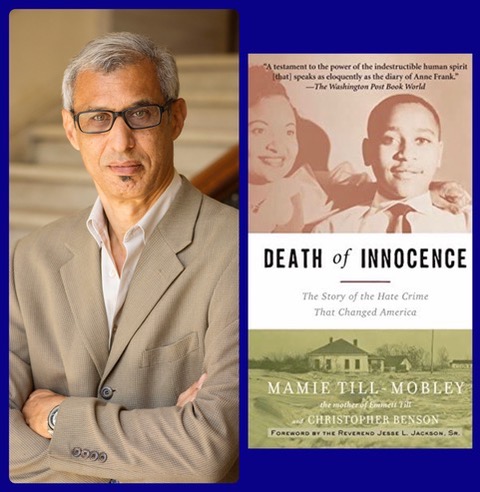

Marion as narrator and host, you kept the tone even and measured allowing the family to express outrage and describe the horror from their respective prisms. Christopher Benson, a professor at Northwestern University who is the co-author with the late Mamie Till Mobley of the book Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America, was prominently featured and had a profound perspective. The dramatic photos were vital in complementing the narrative. Given the nature of this horrific crime, your tone could have been heightened and outraged so it was good that you were balanced. How do you respond to that observation?

I tried to present the facts. But I do try to be measured and neutral. One of the things I thought important to do was to illustrate all that happened to Emmett Till happened in a very short time span including the trial. They wanted a speedy trial to put it to bed. I thought it was an interesting piece of history that people didn’t know or understand that everything happened – from murder to exoneration – in all of 80 days. That’s part of the context.

You also did a masterful job of capturing the taut atmosphere at the trial – the fear in the courtroom and the courage of those who testified knowing that their lives were on the line. But, as the documentary attests: They were willing to die to get justice for Emmett Till. Against this atmosphere of fear, what was the climate in the lead-up to Emmett Till’s horrific murder? And what is its nexus to the civil rights movement?

In the documentary, Benson gives a timeline on the climate in Mississippi at the time. There was a lot happening. Historically, the decision in the Brown v. Board of Education was handed down on May 17, 1954. On May 31, 1955, the court ordered the states to end segregation “with all deliberate speed.” On May 7, 1955, Rev. George Lee, a field secretary for the NAACP, was trying to register citizens to vote in Belzona, Mississippi when he was murdered. Days before Emmett arrived in Mississippi, Lamar Smith, a farmer, and civil rights activist was killed on the lawn in front of the Brookhaven, Mississippi courthouse. A few months later in December 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat and said that Emmett Till’s murder inspired her. The documentary reveals that Myrlie Evers (widow of Edgar Evers), recalled how her husband was so upset by the Emmett Till saga that he was moved to tears. Many believe Till’s lynching energized the civil rights movement.

Mamie even joined the NAACP’s speakers circuit and became a fundraising favorite because she connected to the audience as a mother. Performing this role for no charge – and being unemployed — Mamie asked for money to cover her time and expenses. This request created a fissure and Mamie’s relationship with the NAACP fizzled. Mamie was invited to participate in the March on Washington. But in the spirit of protecting her, Mamie’s mother never told her about this invite — certainly a missed opportunity to revive the story and Emmett Till’s memory before a sympathetic and fired-up crowd.

Similar to today’s political climate, off-shoot stories seemed to swirl around the Emmett Till tragedy. Years after the trial, there was a whispering campaign instigated by Mississippi Senator James O. Eastland. It was about Emmett’s soldier father Louis Till who served in World War II. He was accused of murdering two white women and raping another white woman. He was court-martialed, arrested and found guilty, resulting in his hanging in 1945. In white supremacist circles, this was used as a wedge to justify Emmett’s murder.

What most impressed you/depressed you about the Emmett Till story?

(With a sense of pained outrage.) Emmett Till was 14 years old. FOURTEEN! He had just turned 14 on July 25. He was a boy. He wasn’t a strapping, huge man. HE WAS A BOY!

What role did the media play in both murders?

In both cases, the media was all over it and both got international coverage. Everyone – not just Blacks — saw the injustice against George Floyd. We were well aware of the many, many, many instances. Floyd was caught on camera. It was so irrefutably terrible. So entirely wrong. The whole country saw it. You couldn’t look away. You couldn’t deny that this was an injustice. Similarly, the advent of television occurred during the time Emmett Till was murdered. The story penetrated the news and the world saw it and was horrified. For both tragedies, the news was beamed worldwide.

It’s been 66 years since Emmett Till was brutally taken. And yet, the case was recently closed without charges being brought — despite decades of investigations. In fact, Kevin Cross, President and General Manager of NBCUniversal Local Chicago said: “Emmett Till’s family never found justice. The investigation is closed now. At NBC Chicago, we recognize the importance to keep this story alive and reflect on how far we’ve come and how much more work needs to be done as a community.”

So, in light of this, how do you respond?

The Leflore County grand jury didn’t bring any charges in 1955. The state could have indicted and federal charges could have been brought up on civil rights violations. But that was during the Hoover era and they didn’t have the will.

Justice won’t come from the legal community but this doesn’t mean Emmett Till won’t have a legacy. This is all part of this legacy…. in his short life and in the memory his mother kept alive. He helped bring about a reckoning. He should have grown up, gotten married, and had children. But like so many African-American men, they end up becoming martyrs. It’s our responsibility – journalists, educators, authors, historians — to tell these stories and keep the truth out there. We can still honor his legacy by keeping it alive. That way, his death isn’t in vain.

You say it’s important to tell these stories. Are there any other Emmett Till-related stories being planned?

Yes. NBC 5 has other Emmett Till pieces in the works including a co-production with Collaboraction, a local theater company. The production, titled, “Trial in the Delta,” whose script Collaboraction owns, will bring the adaptation of the trial to the stage. It will air on an NBC platform in the coming months.

Ultimately, what do you want viewers to unpack from this documentary?

I want viewers to know exactly what happened to Emmett Till and understand the context around what happened to him. You can’t discount what happens to our people, and it’s essential for people to remember what happened and know the truth. Hopefully, when the public can make connections, this may produce the spark that will spur action. These are the things that shouldn’t happen anymore. If Mamie Till Mobley hadn’t consented to have this photo in Jet Magazine, we might never have known about Emmett Till. Understanding the history is critical.

We at NBC5 Chicago are committed to keeping the story alive and getting people thinking and talking about it. I hope people will watch the documentary and tell people about it. Rich Samuels inspired me with his comprehensive telling of the story. We took Rich’s work and carried it forward in this original documentary. Hopefully, this documentary will inspire others in their community. There are plenty of injustices that we don’t know about, and hopefully, another journalist, historian, educator, or scholar will uncover and expose these injustices.

Marion, departing a little, you are a veteran at NBC5 and come into our homes every weekday. Would you share a few little tidbits that the public may not know about you? First question: If you hadn’t become a TV anchor, what would you have become?

Oh, definitely, a lawyer.

And who’s your favorite artist?

Sade.

What’s your favorite movie?

I love a movie from the 1940s – Gaslight. It is, unquestionably, my favorite.

And finally, Marion, you’ve been at NBC5 Chicago since 1998. You’ve won countless awards and reported on thousands of stories. In your body of work, where does this documentary rank?

Right at the top…right at the top.

Thank you, Marion.

Melody M. McDowell is a seasoned writer and veteran publicist. She is a freelance writer. Her public relations firm, MELODY’service has been in business for 40 years. She once served as the personal publicist for Dr. Mae Jemison, the first woman of color to launch into space.

Melody is a proud member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority and served as its publicist for eight years, including in 2008, its Centennial year. Melody lives in Markham, Illinois — a city she has grown to love after transplanting from Chicago. Melody also loves cats.