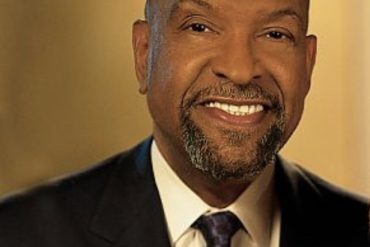

Bruce Harrison sat at a table in the mahogany-paneled bar of Chicago’s Union League Club. He spoke softly, occasionally pausing to take a sip from a glass of moscato.

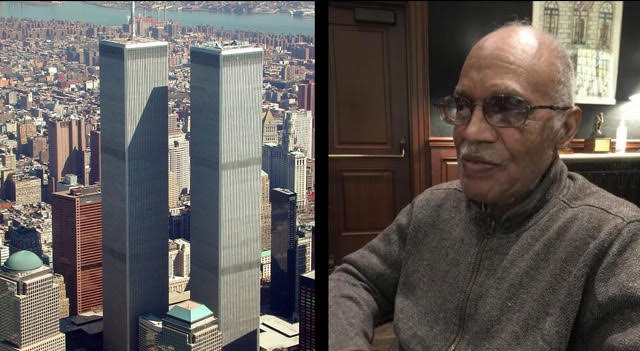

With the 20th anniversary of the 9-11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center approaching, Harrison, still military fit at age 92, reflected on the time he spent as one of a seven-person team of architect-designers on the Minoru Yamasaki masterpiece. It was the professional highlight of his long and full life.

In the summer of 1965, Harrison worked for prominent Chicago architect Mark Kalischer on commissions of luxury homes on Chicago’s North Shore, funeral home for alleged mob boss Frank Granata and public housing for senior citizens.

Kalischer’s two-person shop had received the commission from a Chicago-based restaurant chain for its restaurants nationwide, except in California.

The chain was a fast-food hamburger joint named McDonald’s.

But Harrison, who was 36 at the time, had been offered a position as a designer on the largest architectural commission in the world, the World Trade Center in New York, headed by Japanese American architect Minoru Yamasaki, based in Birmingham, Mich.

How big could a fast-food chain ever become, thought Harrison? By contrast, the World Trade Center would surely stand forever as an invincible monument to architectural prowess.

His choice was simple.

“When Yamasaki got the commission, that was the most famous commission in the world,” Harrison said. “Every architect around the world wanted the job.”

So, in the fall of 1965, Harrison packed his bags and moved to Birmingham, Mich., to join the World Trade Center, design team.

The Early Years

Born into the Great Depression, one week after the stock market crash of Oct. 29, 1929, Harrison grew up in Harvey, Ill., home of the equipment manufacturer Whiting Corporation. His father, William “Bill” Harrison, worked as an auto dispatcher and driver to the Whiting president, Brig. Gen. Thomas S. Hammond. Bill had been Hammond’s chef and driver during World War I. So when Hammond’s son took over the company, Bill drove for him as well.

Born into the Great Depression, one week after the stock market crash of Oct. 29, 1929, Harrison grew up in Harvey, Ill., home of the equipment manufacturer Whiting Corporation. His father, William “Bill” Harrison, worked as an auto dispatcher and driver to the Whiting president, Brig. Gen. Thomas S. Hammond. Bill had been Hammond’s chef and driver during World War I. So when Hammond’s son took over the company, Bill drove for him as well.

When Harrison was a young boy, his parents built a home in an integrated Harvey neighborhood. He attributes his interest in architecture to his childhood memory of helping the builders dig the hole for the foundation and basement of his family home.

At Harvey’s Thornton Township High School, where Harrison was a star running back and linebacker, he took architectural and drawing courses, becoming an accomplished draftsman. Harrison continued his architectural training for one year on a football scholarship at Thornton Community College until he was drafted during the Korean War.

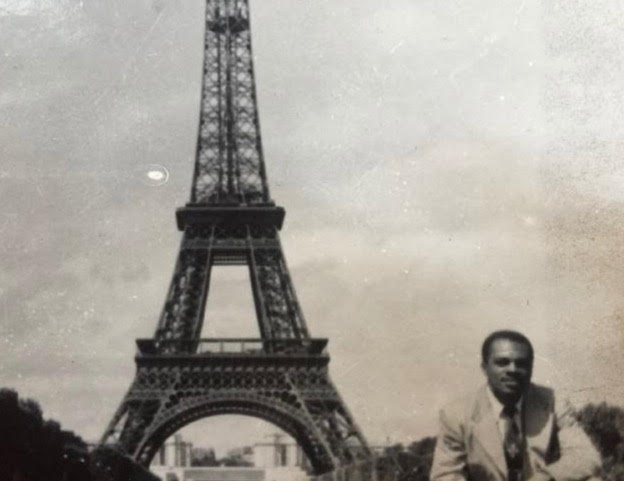

Europe

In the Air Force, Harrison’s architectural training proved to be a gift. He was sent to Europe instead of Korea and was assigned to the U.S. Air Force headquarters in Wiesbaden, Germany. In 1952 he was sent to work in the offices of Nahoff Architectural Studio, a German firm commissioned to design airports in Europe before and during World War II.

Harrison said he presumed the group of German architects with whom he worked side-by-side at one long drafting table were all former Nazis. He used to tease them about losing the war.

“They all were very nice,’’ Harrison said, peering over his glasses knowingly. “We got along fine.”

After a year, a civilian from the Joint Construction Agency, JCA, based in Paris, visited Wiesbaden to retrieve some drawings. He admired Harrison’s work and soon invited him to join the three-person JCA office in Paris.

Harrison’s two years in Paris were a heady time. At JCA, Harrison was a drafter and designer for U.S. military facilities and airports in Europe.

Although Harrison never met Richard Wright, James Baldwin, or Josephine Baker in Paris, he was aware of their presence and was swept up in the romance and culture of the post-war City of Lights.

Harrison, the No. 1 running back in Illinois while in college, played football for NATO in Paris. Here again, he was the No. 1 running back. NATO played against other U.S. military teams in Europe and American celebrities who visited Paris, such as Clark Gable, Marilyn Monroe, and other celebrities who attended its games.

“We had a hell of a good team,” Harrison said. “Two of the guys on the team were Chicago Bears players who were fulfilling their military duty,” including linebacker Joe Fortunato.

Harrison said he considered staying in Paris to study architecture. But Chicago was the premier architectural city globally, and the tug of family ties proved too strong.

He would never return to Paris.

Chicago

Back in Chicago in 1955, Harrison enrolled at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where he resumed his architectural studies. He moved into an apartment at 6445 St. Lawrence Ave.

Mamie Till and her son Emmett lived a few doors down the block. Harrison would see Emmett playing in the neighborhood.

Later that summer, Harrison would learn that his young neighbor had been tortured and murdered by American terrorists while visiting relatives in Money, Miss.

In 1956 Harrison received the University of Illinois General Engineering Grand Award of Excellence. Three years later, he won first prize in a Forest Park Foundation design competition for his design of a senior citizen home in Peoria, Ill. His professor had entered him into a national competition without his knowledge. When the judges asked the professor for the name of the First-Place winner, the instructor confessed to a shocking jury that Harrison was still a student.

Harrison graduated from the University of Illinois at the top of his Architectural Design class in 1961.

After graduation, he would benefit from his father’s relationship with the Hammonds. One of the Hammonds was a partner at the venerable Chicago architectural firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

At Skidmore, Harrison worked under such well-known Chicago architects as Walter Netsch, the U.S. Air Force Academy designer, Chicago’s Inland Steel Building, the University of Illinois Chicago Circle Campus, and Bruce Graham, the designer of Chicago’s Sears Tower, Daley Center and John Hancock Building.

Harrison worked closely with Netsch at Skidmore, particularly on the UIC campus. As a result, Netsch promoted him to the senior designer after seven months. Harrison worked there until he joined Kalischer in 1963.

When the time came for him to inform Kalischer about the offer from Yamasaki, Kalischer hated to see him go, Harrison said. But the older man understood it would be hard to turn down an opportunity to work on the World Trade Center.

Yamasaki…

In 1965, Harrison arrived at the Minoru Yamasaki office in Birmingham, Mich., but not to an apartment there. Harrison had to live in Detroit.

“Birmingham was ranked the No. 1 town of that size in the country,” Harrison said. “I couldn’t find a place to live in Birmingham because it had restrictive covenants that didn’t let Blacks live in the city.”

“Don’t feel bad,” Yamasaki told him, who at the time was one of the most famous people in Michigan and held the biggest architectural commission in the world. “I can’t live in Birmingham either.”

“Racially, he could really understand me,” said Harrison, who would be the only Black person in the office.

Yamasaki, called “Yama,” was a Mid-Century Modernist, yet he did not adopt the Brutalist and Revivalist styles of the time, said Kip Serota, a designer on Harrison’s trade center team. He was criticized for his use of ornamentation and his decorative designs were dismissed as “too lacy.”

Yamasaki was enamored with the Doge’s Palace in Venice, the Taj Mahal and traditional Japanese gardens, according to a 2002 New York Times Magazine retrospective. And it was Yamasaki’s use of decorative effects that caused his buildings to stand out among the geometric, utilitarian, glass-and-steel structures of his peers.

“[Yamasaki] had a different aesthetic,” Serota said. “He wanted to do what the common man related to and liked, and his buildings were widely copied.”

In the spring of 1962, the Times wrote, the Port Authority of New York sent Yamasaki an unsolicited letter inviting him to join the design competition for the World Trade Center. The budget would be $280 million.

Designing the World Trade Center’s Plaza and Lower Tiers…

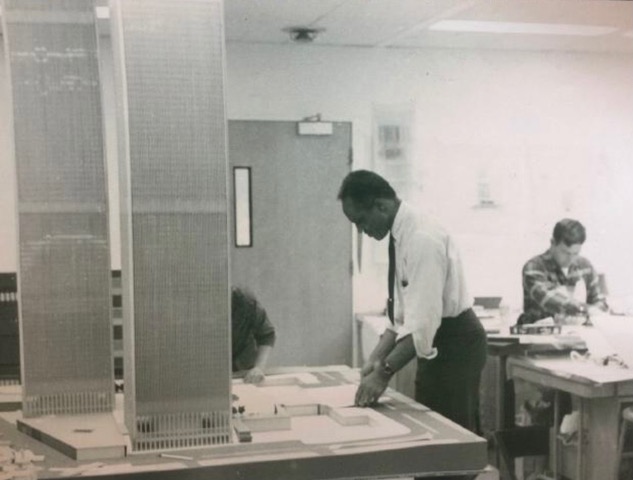

Harrison joined the Yamasaki firm after the trade center project was already underway. He worked there from 1965 to 1967 on a seven-person team comprised of an international group of architects.

“Yamasaki already had a world-renowned international reputation when the trade center project came into the office,” Serota said. “Young architects from wealthy families all over the world flocked to the Birmingham office.

“They came through and worked for almost nothing, got their resumes stamped and went off to start their own offices in their home countries, using Yamasaki’s name as a springboard,” Serota said. “We had the son of the mayor of Rome and the son of a Venezuelan ex-dictator.”

“Bruce wasn’t one of the privileged people,” Serota said. “He was a very good guy.”

Harrison said his team members “respected” that he was from Chicago, the birthplace of the skyscraper.

“The group dynamic was very positive,” he said.

Harrison’s team worked on the plaza and the lower levels of the trade center. In all, there were seven lower levels. The two levels below the plaza were shopping centers. The bottom level was a subway station, the largest in New York. The parking levels were in between.

It was exciting yet exhausting work. Sometimes the team would work all night to prepare for a visit from the New York owners or to meet deadlines, Harrison said.

“We all worked pretty closely together and when certain stages were approved by the Port Authority, we would go out and celebrate,” he said, lighting up at the memory of the Motown celebrations.

Project manager Aaron Schreier, now deceased, coordinated with New York.

“What those guys did was unimaginable,” said Schreier’s son David, now a lawyer in New York. “These guys were very smart men and what they were doing was insane.”

The infectiousness, enormity and excitement of the project trickled down to young David, a first-grader at the time, who boasted at show-and-tell that his father was building the tallest building in the world.

The teacher sent him to the principal’s office for lying, David said, and the principal called his mother.

“David’s not a liar,” Mrs. Schreier told the principal. “He’s just got a big mouth.”

Epilogue, 9-11

Harrison stayed with Yamasaki for almost two years, leaving in May of 1967 to obtain a graduate degree in architecture from the University of Michigan. After that, he stayed in Ann Arbor teaching architecture and consulting on projects for clients such as Bechtel Engineering while working on a Ph.D. in Psychology.

While there, he met his wife, Linda. The couple married in 1970, had two daughters, and divorced in 1975.

Back in Chicago, Harrison went from building buildings to buying them, becoming a real estate investor.

His work on the World Trade Center was an important period of his life, and for decades it remained a pleasant memory, almost a dream.

But as “a cathedral of commerce and capitalism,” as the Times called it, the World Trade Center was an attractive target to terrorists who opposed everything it represented.

At midday, on Feb. 26, 1993, terrorists detonated an estimated 1,000 pounds of explosives, packed into a rented van on the second parking level, killing six people. The resulting crater was “half the size of a football field,” the Times reported.

Harrison was “devastated” by the destruction.

“They said at that time they would be back,” he said.

And return, they did. Then, on Sept. 11, 2001, Harrison watched as the towers collapsed.

“I was glued to the TV all day–all week,” he said. “I was thinking of all the work and time spent on the towers—thinking of Yama and all of us who worked on it.”

Harrison looked upwards and then down again as if appraising the ghosts of the long-lost towers.

“I feel privileged to have been involved.”