David Smallwood was a quiet guy and always the last person in staff meetings to speak. He was a great listener. He was a writer’s writer and an editor’s editor. He worked quietly and wouldn’t answer the phone when he was writing. When writing, he closed his office door as he sipped on a pot of tea. He taped his interviews and transcribed them. Then he wrote his stories.

His friend, Derrick Baker, said, “The lifelong journalist, editor, observer, and commentator painted pictures with words; he used language to connect people; he used media to tell stories, motivate readers, entice supporters, educate sponsors to inspire the uninspired and bridge relationships that didn’t even exist before his writings.” That’s a perfect description of David at this best.

Sunday afternoon is my quiet writing time listening to my favorite jazz. Today is extremely somber. I usually talk to David to discuss topics of the day. I miss him terribly already as I constantly cry, thinking of his funeral on Wednesday, June 23rd. David passed on June 11, the same day the city was fully opened from the pandemic by the Mayor. David passed of Covid-19 and rare bone cancer. He took the vaccine. He passed before Juneteenth became a holiday. He died before the major columnists took the buy-out at the Chicago Tribune. These are the things we would have talked about on a Sunday afternoon. I might have told him all of these years we have been writing about “critical race” issues. He would have laughed.

N’DIGO – Day 1

I started N’DIGO in 1989 after being sick and tired of the mainstream press omitting Black life from its pages. I was sick of the crime stories, the constant diet of negatives, and the attack on Black public officials. I saw racism in the white mainstream media and wanted to change the narrative and images of Black people.

David and I worked together at the City Colleges of Chicago. He was the Communications Director at Olive Harvey, and I was Vice-Chancellor at the central office. He was one of the first people I spoke to about my newspaper idea. We met, and as usual, he was quiet as he listened to this new concept.

One Saturday morning, I had a meeting with journalists, photographers, graphic artists, writers, activists, and others. I told them about my paper idea. David was experienced and gave credence to the concept. After the meeting, when everybody was gone, he asked if I was serious. I replied, “Yes, I am. ” He said, “I am with you,” and he meant it. His words were golden. He never wavered. He understood the purpose and mission. We couldn’t just complain when we could do something.

David was mentored by Lu Palmer, the founder of Black X-Press, where he was a student reporter. Lu, too, was concerned with the marginalization of Black thought and opinions. It was the same reason that I started NDIGO.

David worked at the Chicago Sun-Times as a copy boy, wire room clerk, library clerk, and reporter. He was Associate Editor at Dollars and Sense Magazine (defunct). In addition, he was the Entertainment and Associate Editor for Jet Magazine. He also worked at The Chicago Reporter for a year.

David knew the craft of writing. He knew the technical aspects of writing for newspapers, word counts, headlines, and the like. He could take us to press. He was a newspaperman, always in search of a good story. He knew the mechanics of producing a print product beyond writing. It requires a team in sync.

Together, we developed a great team of writers who sometimes wrote for significant outlets under assumed names. I wanted to change the narrative on Black life in Chicago with words, photography, and perspective. I wanted emerging writers as well as the veterans who could not write “freely.” It was time for “new” news about Black folk. It was time for a new image and time for a change in the media. We were Black Lives Matter before they were born. We were about “critical race” before it became critical. We were civil rights people who lived change. We changed the narrative. Our motto became, “we tell stories, untold, mistold that need to be retold.” We did it. David made it happen consistently. David was “Grammarly” before they went to market. Our stylebook capitalized the “B” in Black before the New York Times. It was our introductory editorial.

When his wife Louise was delivering their first child, Danielle, we took bets in the office that the baby would arrive on a Tuesday – paper night. As it happened, David worked the night and went to the hospital to visit his newborn. Unfortunately, he fell out on Wednesday afternoon. He wouldn’t let anyone help with planning for the baby’s birth date.

We begin. He never left. He and I became great friends. He was my muse. Every idea I had, I talked to him about it first. Sometimes he just nodded and said, “when”? Sometimes he said to do it this way, not that way. Sometimes he said it wouldn’t work. But, he was primarily encouraging and patient, observant and careful, with a smart-ass remark coupled with a sweet demeanor.

We worked diligently with extreme focus. David loved finding new writers and coaching them. He loved the creative process. He worked hand in hand with our graphic artists, Steven Johnson, fresh out of school, and the seasoned Darnell Pulphus to produce a quality, beautiful product. Like a soldier, he brought up the rear. The rule was don’t send the paper out until David sees it. It didn’t matter who wrote it. It had to pass David’s scrutiny. His edits made it better. He changed the words, perhaps but never the meaning. Sometimes he would say, what you mean, it’s not what you said. He enhanced and improved. He didn’t argue. He just did it. He was the last one to see the paper. He was an editor’s editor with the final say – the boss.

Writer’s Stories

Our political writer, Bob Starks, was famous for routinely calling on Monday nights or early Tuesday mornings to say stop the press. He had a hot, can’t wait, must print breaking news story every single week. Bob missed Friday noon deadlines. I would go off on Bob for being late unplanned, and always unscripted yet David handled him differently. David would tell Bob to hurry up and submit his story, and he would do what he could to get it in. He was stern, quiet, and firm.

David told Bob the presses were waiting for him. Bob’s story was always well done, with political intelligence and insights. But his stories had to be typed. His reports were submitted in a beautiful calligraphy hand. I dismissed Bob and wanted to fire him and would not take his calls between Friday and Tuesday morning. David had to handle Bob on deadline. Eventually, Bob’s stories were refused in his handwriting. David always worked it out. We never stopped the press, but Bob thought we did. David was diplomatic, and Bob kept writing and eventually got his articles typed by a student intern.

Derrick Baker, one of our cover story writers, was David’s dear friend. They worked at Dollars and Sense Magazine together. Derrick presented an excellent idea. He wanted a column providing an urban Black male perspective on Black life. “The Way I See It” was over the top. Sometimes Bob, Derrick, and I wrote about the same thing, unknowingly, and David made editorial adjustments.

The late Barbara Samuels was our fashion editor. Twice a year, she had dedicated issues for fall and spring fashion. She was most particular about photos and “fashion descriptions.” She knew how she wanted her layout. She knew how she wanted her cover. She came in the afternoon to begin work and usually disturbed our regular newspaper rhythm. Who was in charge – David or Barbara? They usually pulled an all-nighter as David challenged her words, and she taught David a thing or two about fashion. One morning I came to work, and there they were having coffee, explaining they had stayed up all night with the paper. David gave me fashion tips, and Barbara guarded her words. Smile.

And then there was our gossip column writer, Wanda Wright. No one ever knew what Wanda would write as she got scoops from everywhere. David had to watch and edit her carefully. We had great conversations on gossip and news, and sometimes I just knew the angry phone calls would come. David would say as long as she is telling the truth and can prove her stories, we are okay. They went at it, often. She always had the juicy copy, sometimes too salacious to print.

Come Tuesday…

Tuesdays were production night. David asked for a couch for his office and sometimes slept on it as we prepared for the press. He read every story. I usually left him at the office, sometimes awakened in the middle of the night with a trivial comment or question. He would often call to tell me when the paper had been submitted to the printer. This was our usual flow. A call at three o’clock in the morning was the norm, and I am sure it was done to irritate me.

September 11, 2001, was a horrible day. First, it was paper day. Second, downtown Chicago was emptied after planes crashed into New York’s World Trade Center that morning. Third, we were under attack; what do we do?

Our offices were located in the Sun-Times building, 401 North Wabash. The building is now Trump Tower. I called everybody together, uncertain of whether to go home or change the paper. The planes crashed at 8:45 am. We met around 10 am. The paper was just about ready to go to press. We collectively decided to redo the paper entirely. Everybody had to work. All hands-on-deck. David assigned everybody a task as we watched the news and wrote. We worked with precision on a tough day and pulled together with David’s leadership. We kept it moving, producing a paper on September 11. It was a fete for a small newspaper.

David observed and listened. He was quite the interviewer. He checked the facts, crossing the t’s and dotted the i’s. He made it better. He improved it. He never let me make a mistake. If I wanted to profile someone on the cover, who shouldn’t be, he caught it. He knew the meaning of words. So many of the people we featured would never have such coverage before or after, and we had to get it right. He knew the beauty of words because he was a wordsmith. He knew the power of words; he knew we could bring about change. I wanted empowerment for our brand. We had an insight that others in the media did not.

He best described himself as an “established print journalist, author, editor, content generator and media consultant in the Chicago area. I have well over half a million of my own words in print under my byline in newspapers, magazines, and books,” he wrote,” and have edited about two million words of other writers that have seen the printed page and appeared online.”

His words ring true and most accurate in describing his quiet soul. He was born February 1, 1955, to Annie Mae Smallwood and Frank Cook. He is a graduate of Dixon Elementary School and Lindblom High School. He was awarded a 4-year National Achievement Scholarship from the Sun-Times to the University of Illinois, where he received his Bachelor of Arts Degree in journalism.

The Publisher’s Page…

I wanted a page in the paper to provide perspective on current issues. I was following the footsteps of Mike Royko and Vernon Jarrett. David was thinking about Lu Palmer. I couldn’t get the right person to pen the article. David challenged me to write it myself. We will call it the Publisher’s Page.

He made my writing better, sharper, and even profound. He was a master writer and caused me to rise to the occasion. He could always interpret my thoughts and knew what I intended. He turned sloppy into excellence, indecisiveness into confidence, and he turned my academic research style writing into pop culture journalism.

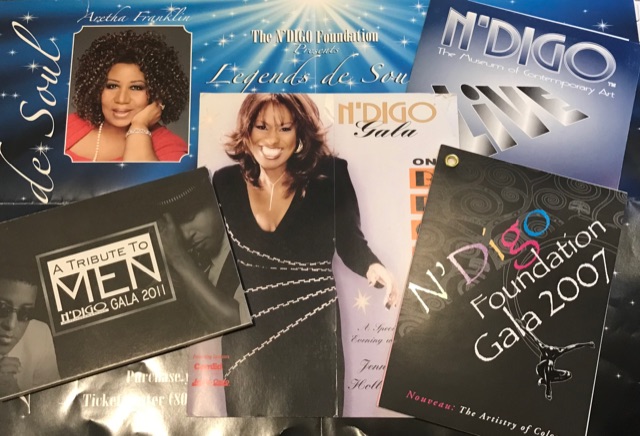

The N’DIGO Gala…

I started the N’DIGO GALA, in 1995 and we held a fabulous black-tie event annually for 20 years. David worked with the honorees and the scholars behind the scenes, directing in his quiet way. He kept the excited students together. The students were stellar, and eventually, we dedicated an entire edition to students, featuring them with photos and interviews. David created great moments for the youth; they were in the paper and on stage at the Chicago Symphony Center.

N’DIGO Legacy Black Luxe 110

One day, I said David, we need to write a book. So, we stopped printing the paper in 2017. When Newsweek stopped printing, I read the tea leaves for small newspapers. Print media was shrinking, and the advertising game was changing.

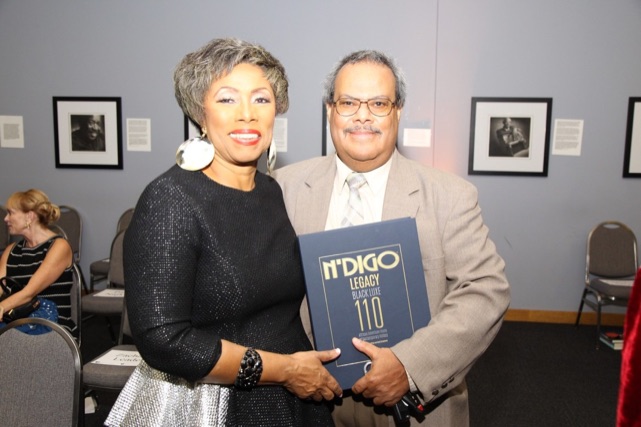

There was history in N’DIGO’s file cabinets. We began writing articles digitally. I said, “it’s time for us to do a book that will be a beautiful history book.” Together, we co-authored N’DIGO Legacy: Black Luxe 110. It is a compilation of N’DIGO cover stories of Chicagoans who made an impact. It was supposed to be 100 stories, but grew to 103 and finished at 110. I wrote. He wrote and edited. I wrote. He edited every story with updates and preface. We had a wonderful rhythm and after a year, we had a book.

The book was edited six times by different editors. The evening we introduced the book in 2017, I told people I was the mother of NDIGO and David was the father. N’DIGO was our “child.’ It was with pride and joy that we presented the book to those who were profiled in N’DIGO Legacy: Black Luxe 110 at a beautiful luxury jewelry store on North Michigan Avenue.

We both were honored as a part of Chicago Public Library Carl Sandburg’s authors. It was a great moment as we were recognized. We gave Chicago an authentic Black history.

David loved teaching. He taught by example. Two of our writers, Zondra Hughes and Jenice Drake, became editors under David’s tutelage. David groomed writers.

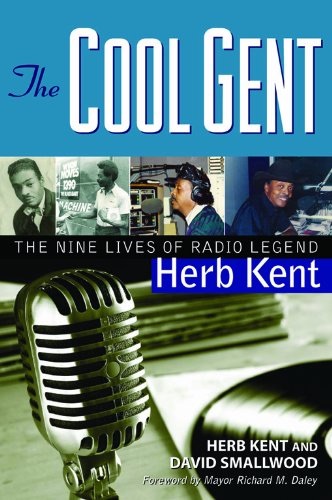

David admired the late Herb Kent, the long-time, famous Chicago disc jockey. He had Kent write articles. Herb knew every entertainer from his era and had so many stories to tell. Herb playing a record was a make-or-break scenario for an artist. Once, Herb called me to say; I don’t want to mess up your paper. I am intrigued by David’s idea, but I can’t write. So I said, “But David can. All you have to do is tell him the stories, and he will produce the column.” It was a very successful column with Herb’s uniqueness and particular style of storytelling. David took Herb from radio to print.

Eventually, David and Herb co-authored The Cool Gent: The Nine Lives of Radio Legend Herb Kent. With research, David found that Herb was the longest-reigning disc jockey in the world. He proceeded to get Herb a Guinness Book of Record Award and presented, to him the same day the book was released.

A Pro…

Nothing was hard. We just gave it to David, and with ease, he fixed it, even when he stayed all night at the office. His office hours were irregular, long before stay at home became popular. He worked his timetable, but he never missed a beat.

David called me one day to say I can’t be the editor anymore. He said, “I am sick and can’t write for now.” I said okay, but you will always be the editor. He said write carefully and remember short paragraphs. Then one day, he called and said, “I’m back. Send me articles for edit.” Another day he called to say I am requesting a writing assignment. I gave him a story on the innocence of Father Michael Pfleger. It was an investigative story by an anonymous person. His last article appeared on April 14. He rose to the occasion brilliantly telling a difficult story. I did half of the work and he did the writing and together we bought it together.

At the time he became ill, David was working on another story. It goes unfinished because he wasn’t ready to file it. He will always be my editor, the editor of N’DIGO. He left a wonderful imprint and legacy on Chicago media.

David wrote, “Whatever I can do for you is what you actually need.” I am lonely without his comments and edits. I miss our conversation to discuss various angles. Unfinished. He will live in the future. His works rest at hhttps://ndigo.com under the archive icon.

A generation of writers will miss him. He leaves a hole in Chicago’s media landscape. His words were always thoughtful, accurate, and mindful. He was a great storyteller, a dedicated journalist. Unfortunately, he suffered from a rare form of cancer, mainly affecting Black males, multiple myeloma, and Covid.

David is survived by his wife Louise Fort Smallwood and their three daughters, Clarissa, Danielle, Emerin, and two sons Christopher and Damon (Mother Latisha Darey). His legacy will also be remembered by twelve grandchildren, a host of nieces, nephews, cousins, and a legion of friends.

Services will be held:

Visitation: Tuesday, June 22. From 6 to 8 pm

Funeral Service: Wednesday, June 23. From 1 to 2. With a repast afterward from 4 to 6 pm

Leak and Sons Funeral Homes, 18400 South Pulaski, Country Club Hills, Illinois.

june 23rd 2021, i am listening to wvon 1690 am radio with perri small,and hermene Hartman is on the show. Great Info.