Although he passed into eternal life the same day as the more nationally known giant of the Civil Rights movement John Lewis, the Rev. CT Vivian is especially revered in Chicago for his yeoman support of us locals in opening up the construction trades here.

A key advisor to Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the Rev. Vivian died at the age of 95 on Friday, July 17, the same day as Congressman John Lewis (D-Georgia), age 80, another lion of the movement.

“CT” as his friends called him, met MLK after the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott and helped organize the first Freedom Rides, which triggered federal intervention against racial segregation in the Jim Crow South.

Many may remember when TV news showed him waving a finger at Sheriff Jim Clark of Selma, Alabama, at which point the Sheriff punched him, cameras rolling, for the world to see.

This fracas more-or-less turned a local voter registration drive into a national crusade. CT was one of the first to lead restaurant sit-ins and was jailed for his efforts to get African Americans the right to vote.

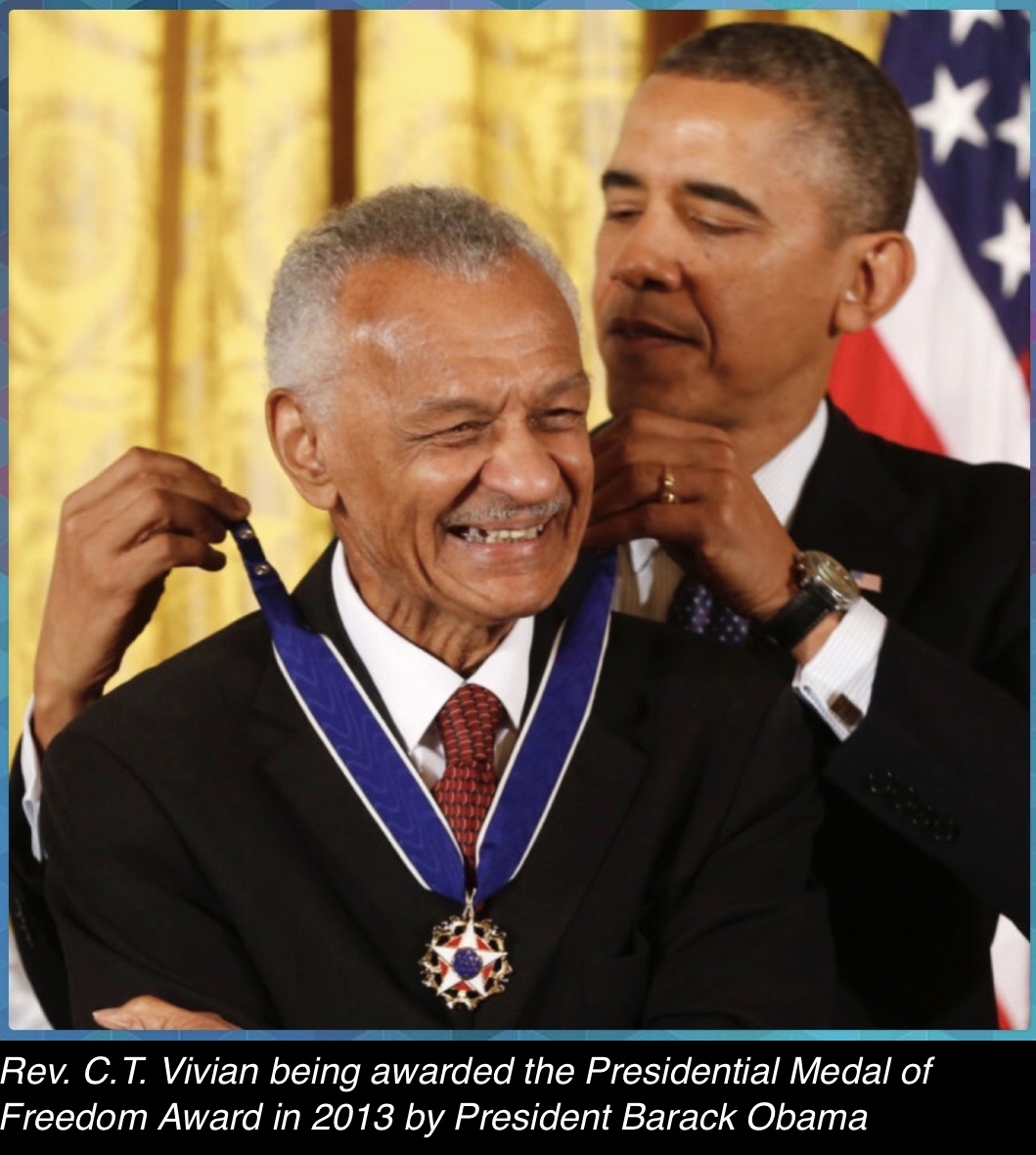

Vivian continued to work with SCLC after MLK’s assassination in 1968. His life’s work would prompt President Barack Obama to award CT Vivian the Medal of Freedom in 2013.

Construction Reform In Chicago

Yet few notices of CT’s death have pointed to the extraordinary leadership he demonstrated here in Chicago during the late 1960s and early 70s. It was Rev. Vivian who convened the effort to challenge racism in the area’s construction industry.

It’s no exaggeration to say that hardly any Black, Hispanic or female union-scale construction workers entering the market after 1971 would have their job if it were not for CT Vivian.

It was CT who convened and created here the Coalition for United Community Action, an assembly of 60 organizations aimed at social and economic advancement for Black people.

The Coalition targeted the Chicago construction trade unions and the AGC (the association of predominantly white-owned general contractors) that negotiated union agreements.) The Coalition’s twin goals were to get more Blacks into the trade unions and get Black contractors into federally-assisted construction projects.

CT’s biggest accomplishment was managing the agendas, priorities and personalities of what was known as the 12 Main. Primary among them were the three LSD: The Conservative Vice Lords, The Black P Stone Nation and The Black Disciples. It was the first and only time that these highly competitive “teen nations” worked together to achieve positive outcomes. Imagine Jeff Fort, Bobby Gore, and Larry Hoover meeting with CT and the other 8.

Why involve organizations commonly referred to as “street gangs?” Because this was the rough-and-tumble Chicago construction industry, not some school board, or genteel, white-collar service sector.

LSD was our troops. We sent as many as 400 out to a construction site to outnumber and – if need be – out-muscle the union hard-hats. CT Vivian’s nonviolent, patient, persistent leadership somehow made it work.

Other members of the 12 were Calvin Morris (Operation Breadbasket), Sally Johnson (Allies for Better Communities), David Reed (Valley Community Organization), Meredith Gilbert (LPPAC), Robert Lucas (Black Liberation Alliance), Fran Womack (The Coalition), Robert Taylor (Welfare Rights Organization), AI Dunlap (The Coalition), Curtis Burrell (KOCO) and yours truly, Paul King, Jr. of the West Side Builders .

This group met almost daily, often as early as 6 a.m., and its members never disclosed the active construction site that was to be targeted for closure that day. CT Vivian was the Catalyst and Convenor.

Shutting It Down!

On July 23, 1969, CT led the first construction shutdown – a HUD-financed project on West Douglas Blvd. It would be the first of $80 million in idled projects to follow.

Once we got everyone’s attention, it was CT’s fearless negotiating style that came into play. He was not loud, just persistent in driving a point home. He gave each of us a voice and a role to play, for he possessed a paternal passion for leadership development.

Another big asset was his ability to shift gears, bantering with white union leaders on one side, then abruptly taking us to challenge the white general contractors. We knew they were united against us…but also that they really didn’t trust each other.

Lastly, CT’s seminary and church sermon preparation put him in good stead in challenging Mayor Richard J. Daley, who chaired subsequent formal negotiations between the unions, the AGC, and our Coalition. He was concise, even-tempered and patient.

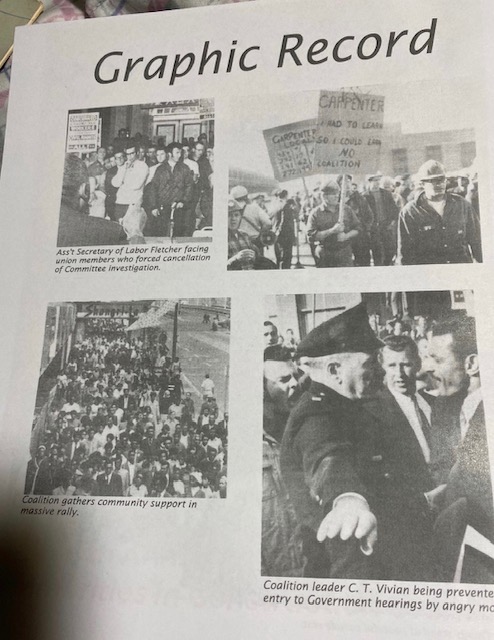

When CT testified at hearings held by the U.S. Department of Labor here in Chicago, he came armed with statistical data supporting our claims. Much of that information was researched and developed by the Chicago Urban League.

The CUL was not in the Coalition because some of our tactics were offensive to CUL supporters. But we worked confidentially and cooperatively…and would have been dead in the water without CUL to back us up.

CT later testified in Washington D.C. and submitted written testimony to the Senate Labor Committee. His focus was Black jobs, but he also turned me loose to advocate for Black contractors.

So how could a Civil Rights minister develop the prescience and genius to go up against an industry that accounts for one out every six jobs in the country?

Troublemakers!

Professor Erik Gellman does us a favor with his recent book Troublemakers – Chicago Freedom Struggles though the Lens of Art Shay. Gellman quotes Rev. Vivian with this terse explanation of what it’s about, then and now: “Because culture has closed (young Blacks) out, they needed to find a way to get in and …. rebuild their own community.”

Gellman explains that our Coalition “sought to pressure the Office of Federal Contract Compliance to hold accountable firms that received these federal dollars but did not practice “affirmative action.”

As CUCA’s protests spread, Chicago representatives of a dozen federal agencies responded by forming the Federal Ad hoc Committee Concerning the Building Trades, whose research confirmed Blacks’ blatant exclusion from the building trades except three.

Nine unionized industries had labor shortages, it found, but they nonetheless continued to discriminate. To many observers inside and outside the CUCA, a revolutionary restructuring of institutional racism in employment seemed possible. “In the summer of 1969,” one federal official remarked, “the Black community in Chicago was better organized than anywhere in the country.”

Chicago Defender editor John Sengstacke agreed, declaring there was “more compact unity behind (CUCA) on this issue than there was behind Martin Luther King in the struggle for integrated housing in Chicago.”

Professor Gellman provides a scholarly, well researched testimony to the brilliance and wisdom of CT Vivian. Gellman continues “In the summer and fall of 1969, they (CUCA) deployed to dozens of construction sites across Chicago, where they shut down several hundred million dollars’ worth of federally funded construction projects.”

Photographer Shay captured one of many confrontations as hundreds of young Black men showed up to take over a construction site. They coerced white workers and foremen to leave the site, making threats, but avoiding violence.

Citing President Johnson’s’ 1965 Executive Order 11246, they declared that all 19 of Chicago’s building trades and its principal training facility, the Washburne Trade School, maintained racially exclusive barriers to unions and jobs.

Gellman has a TRIFECTA here! Accurate description of what actually took place, how he is able to capture the pulse of what was discussed, the challenges and the victories is a research masterpiece.

The photographs of Art Shay are off the chart. To see one of the Black P Stone nation reading James Baldwin is one thing, but to see that phenom in a book is a pleasant surprise. Gellman does a masterful job with his notes. For those interested in further study and lessons learned, Attention Black Lives Matter: Troublemakers is a good place to start.

For Additional Reference Material, the Chicago History Museum is the place to go. The contact is Julie Wrobleski . She is in charge of a collection of documents provided by yours truly that are available to investigate and assess the contributions of CT Vivian and the Coalition he led.

Closer to home and hearth, I wrote a book Reflections On Affirmative Action In Construction – a copy of which I especially treasure because CT signed the title page as follows: “to Paul King, a tireless worker and a friend I never hope not to have.”

And one other thing: In November 2010, CT was initiated into ALPHA PHI ALPHA Fraternity, the first Black Fraternity, founded in 1906, of which I am a life member. Into that same line of Atlanta initiates was another icon, the Rev. Joseph Lowrey, along with a very special hero of mine, my son Tim King. At Tim’s Urban Prep Charter Schools, young Black men continue to, in CT’s words, “find a way to get in.”

Rest in peace, CT Vivian, for your work lives on.

Paul King is a construction industry consultant and member of the Business Leadership Council.