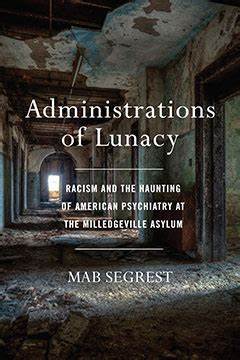

ADMINISTRATIONS OF LUNACY: Racism and the Haunting of American Psychiatry at the Milledgeville Asylum

By Mab Segrest

The New Press

Publication Date: April 14, 2020

Price: $28.99 hardcover; 416 pages

In her new book, Administrations of Lunacy, author and social activist Mab Segrest has dug deep into the chilling history of the Georgia State Lunatic, Idiot, and Epileptic Asylum – otherwise known as “Milledgeville” for its location – to discover how modern psychiatric practice was forged in the traumas of slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow.

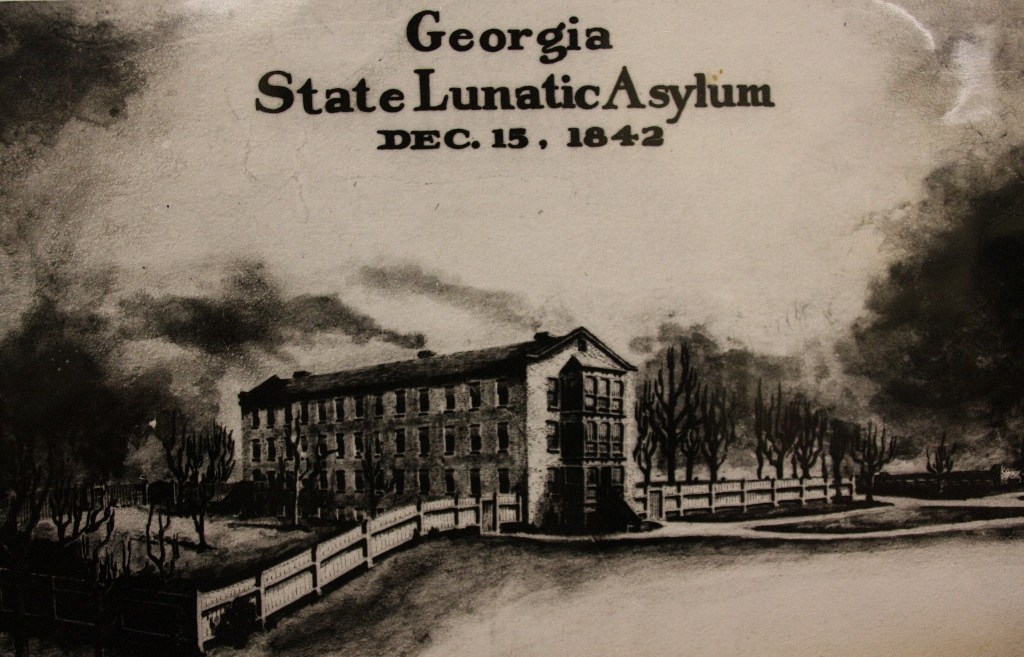

The Milledgeville asylum opened in December 1842 and 100 years later, it had become the largest insane asylum in the world, peaking with over 13,000 patients. Segrest tells the story of this iconic and infamous southern institution, a history that was all but erased from popular memory and within the psychiatric profession.

Connecting the institution’s history to the modern era, Segrest uncovers the factors that helped set the stage for the eugenic theories of the 20th century and for the persistent racial ideologies that continue to have devastating consequences in our own times.

She examines such issues as how theories and practices of psychiatry recognizable today originated in U.S. asylums, promulgated by people who defended slavery, profited from the removal of native peoples, and supported sterilization of people considered “unfit” and why this historical context is critical to understanding issues of diagnoses and treatment today.

The book connects a vital thread between past and present and reveals the tangled racial roots of psychiatry in America. Spelman College professor Beverly Guy-Sheftall says, “Segrest’s research foregrounds the shameful connections between white supremacy, Cherokee removal, slavery, patriarchy, and the psychiatric profession over the past century and a half in the South.”

Mab Segrest was born in 1949 in Birmingham, Alabama and grew up in Tuskegee, where her family on both sides had lived for over a century. Her childhood experience in Alabama’s apartheid culture shaped her future work as an activist, writer and scholar. Her books include Memoir of a Race Traitor. Segrest, who earned a PhD in English from Duke University, made the following comments about her new work.

In your first book, Memoir of a Race Traitor, you discussed your experiences combatting racism in the South. In what way is that book connected to your new book?

Mab Segrest: Let me begin by explaining what I mean by “settler colonists” and then you’ll see the connection between the two books. Centuries ago, in Africa and Asia, Europeans usually conducted their business from fortifications and limited their emphasis to trade, given the geographic, political and climatic considerations of those vast continents. But the Americas, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa became settler colonies, in which the British came to conquer and stayed to make their homes and their fortunes.

Only in the Americas did European colonists import Africans for slave labor. It is from this combination of settler colonialism and chattel slavery that the particularly vicious character of U.S. racism emerges. In Memoir of a Race Traitor, I trace the impact on generations of my family as they emerged as settler colonists. In Administrations of Lunacy, I show the impact that these violent colonizing processes had on the peoples they conquered and on their own mental stability.

Administrations of Lunacy examines the arc of how racism shaped modern psychiatry in the United States. Talk about your research and conclusions.

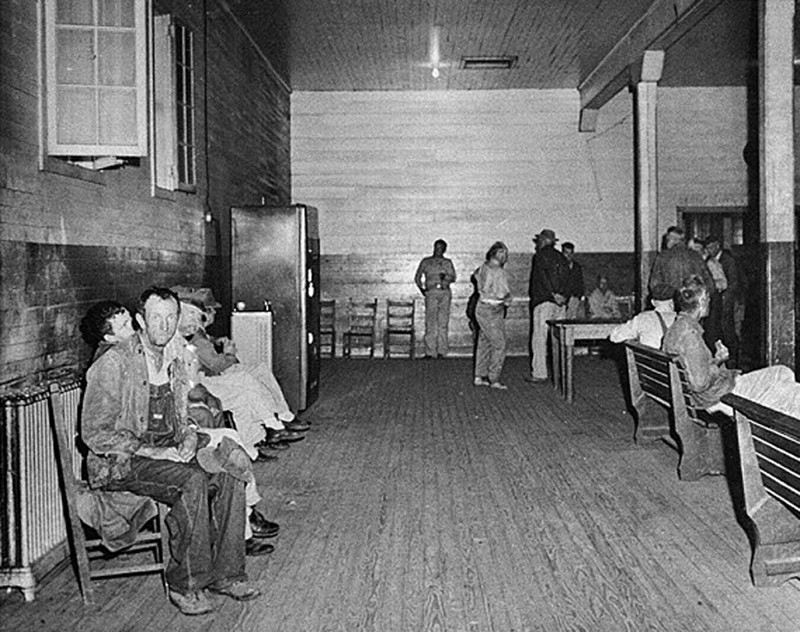

I began my research with a deep curiosity about what I would learn from a close study of an asylum founded in a slave culture such as Georgia’s; that’s not usually the point of view from which asylum psychiatry is studied. I also asked myself how a culture that allowed – and even celebrated – lynching after Emancipation could decide who was and was not sane? In addition, I was very attuned to the brutal health disparities that evolved as Milledgeville became a segregated psychiatric institution after 1867.

In 1867, the institution accepted its first Black patients, who were housed in what was called the colored building. It gave me the chills as I went through all these ledgers, roll after roll of microfiche, to see the first Black patients. There was something about them having been through slavery and the Civil War…and then to end up in the Georgia asylum. It seemed like such an exhausting and perhaps gruesome trajectory.

In 1893, there were 1,146 white patients and 530 black patients. Beyond basic clothing, white female patients got palmetto fans, writing pens, envelopes, spectacles and toothbrushes. Black female patients only got irons.

Based on data in annual reports, I could see how the institution unfairly distributed both its work requirements and its goods by race and gender. I also came to see how antebellum ideas about race and Black people contributed to the rise of eugenics in the United States.

From there, I started thinking about how the releasing of patients from state hospitals for “community care” from the 1950s onward overlapped with the Reagan administration’s economic policies that transferred funds from social welfare to the military and the prison system. This led to a system of mass incarceration replacing “community care” which became “the New Jim Crow.”

From there I was able to answer another larger question: Why are 90 percent of state psychiatric beds in jails and prisons today? In the book, I then ask what is the responsibility of the psychiatric profession in dealing with this travesty? How does this pattern of racism affect the mental health of us all?

How did you become interested in the Milledgeville asylum? What did you expect to find? What kept you working on this book for 15 years?

Three factors converged in what became the most ambitious writing project of my life. First, I learned when I was in my thirties that my great-grandfather had died in Bryce’s Hospital, a mental institution in Alabama, in 1901. Second, like many people my age, I was threatened as a child that I could get “dragged off to Bryce’s” if I was too peculiar.

Third, I loved southern writers of the 1940s and 1950s, like Carson McCullers, Flannery O’Connor, and Tennessee Williams, each of whom used the terrors of their respective hospitals in their stories. All of this made me want to learn more about the concept of “southern insanity.” As I worked, I kept finding additional archival material and that pulled me further into the story. Sooner or later, it was too far to turn back.

In the book, there are detailed accounts of real people, both doctors and patients. Is there a particular story that typifies what you learned or that sticks with you?

The story that moved me the most, and the person who grounds the story at its end, is “Mary Roberts” (a pseudonym). She was committed to the Georgia Sanitarium in 1911 for crying, praying, singing and dancing. The doctors were stumped as to whether she was schizophrenic or manic-depressive. But an examination of her medical records shows that she had lost nine of 11 pregnancies in what was an epidemic in Black infant mortality in the early 20th century.

To the irritation of the doctors, she continued her spiritual practices, remaining “exalted on the ward” until, we assume, she died there. I learned from her the importance of understanding cultural context in diagnosis and treatment, and how a person such as Mary in such destitute circumstances can maintain herself and spirit in spite of her environment. When the doctors asked her to deny that the voices she heard were her dead brothers and sisters, she replied, “They are not living, but they are real.” That sticks with me.

The examination of the hospital’s history and the origins of American psychiatric practices are told through the prism of race. Why?

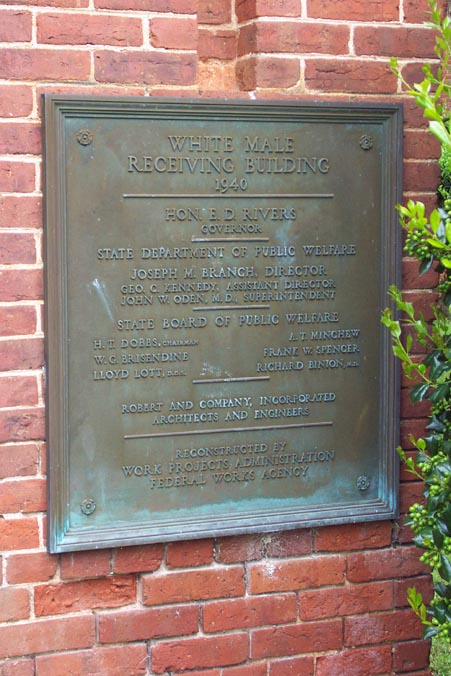

The more I dealt with the material and absorbed it, the more I saw that the through line is race. Why is that surprising? It’s founded in 1842, antebellum era. There were 17 major plantations in Baldwin County before the war, and two-thirds of the legislators who came to the capitol in Milledgeville were slave owners. And from that capitol, the legislature and the governor oversaw both Indian removal and the bringing of slaves. To start there, and to tell the asylum story from there, felt like a new perspective on psychiatry.

What about psychiatric care today – have we achieved equity and justice? Where are we failing?

I focus on two crises in psychiatric care today — treatment and diagnosis. Regarding treatment, remarkably, 90 percent of state psychiatric beds today are in jails and prisons. That is the opposite of equitable and just.

The failure here was the inability of states to provide “community care” in towns and cities when the big and shamefully failing psychiatric institutions emptied out. By the 1980s, austerity budgets redirected money at the state and federal levels to police and the military — thus creating the conditions for psychiatric beds in prisons and jails.

Regarding the crisis of diagnosis, I trace the evolution of diagnostic categories over the 170 years of Georgia’s hospital, particularly the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association begun in 1952 and now in its fifth edition. Over the past two centuries, the worst aspect of the dominant system of diagnosis was the focus on the body as only biology. This bio-medical model did not present patients’ experiences as part of a complex physical and political environment with which the mind and body together always interact.

By extracting history from the explanations of people’s suffering, this state version of medicine did not have to account for the damages of white supremacy, sexism, and poverty in the process that I call “settler colonialism.” Thus, the people most victimized by settler colonial history are blamed for their suffering because they are from “degenerate” populations, not because they have been enslaved, displaced, beaten by husbands, damaged by civil war, lynched – the whole dramatic panoply of southern and American history.

What’s the most surprising thing you found in your research?

How compelling I found the patients to be, how much they still journey with me, and how deep the story was.

What’s next for you? Are you writing another book?

Right now, having worked so long on this book, I want to put my energy into getting it into the world and into the hands of people for whom it will mean a lot. As everyone else today, I am deeply concerned about the pandemic and all too aware of the ways that the history I trace in Administrations of Lunacy helped to land us in this situation today and could help illuminate our options.

Administrations of Lunacy is being published in the midst of a global pandemic. What can your book teach us now as we confront COVID-19?

Public health is one of the heroes of the book, while public policies based on racist delusions that endanger everybody, are one of its villains. In an era when the President declares viruses “foreign” and refuses to institute the most basic preventive domestic measures against the coronavirus epidemic, these categories will strike readers as frighteningly familiar.

Here’s an example from the late 19th century. Asylum Superintendent T.O. Powell explained that African Americans’ rise in insanity and TB happened because Emancipation eliminated the slave system’s healthful effects, which is a remarkably ahistorical claim. Anything that happened to Black people after Emancipation was their fault because they should have stayed slaves, basically. The asylum population grew, with African Americans in increasingly crowded spaces that quickened the spread of TB, which is airborne.

As a result of Powell’s lack of the latest scientific information and his profound bias against Black people, epidemics not only of TB, but also of pellagra and hookworms, proliferated within his institution as he castigated whole categories of people as “unfit.”

On the side of public health, African Americans in Atlanta in the early 20th century declared “germs have no color line” and tracked TB through neighborhoods, traced contacts, and educated their people on prevention and treatment. Surely today we would choose the second set of practices over the first?