The next time you hear a comedian spit a four-letter word from the stage, you may want to consider thanking Lenny Bruce for the entertainment.

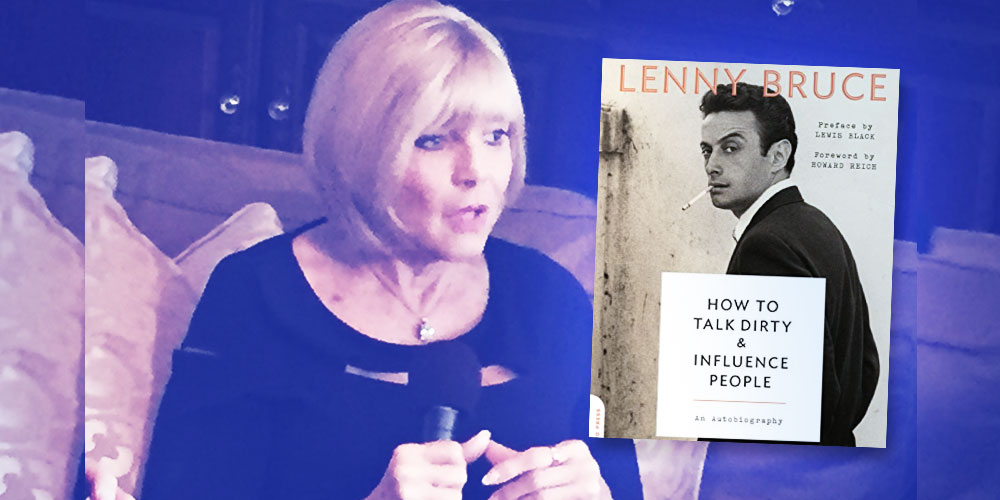

To paraphrase the title of his posthumously released 1967 autobiography How To Talk Dirty And Influence People, the late comic is still talking dirty and influencing folks more than 50 years after his death through a new production about his life.

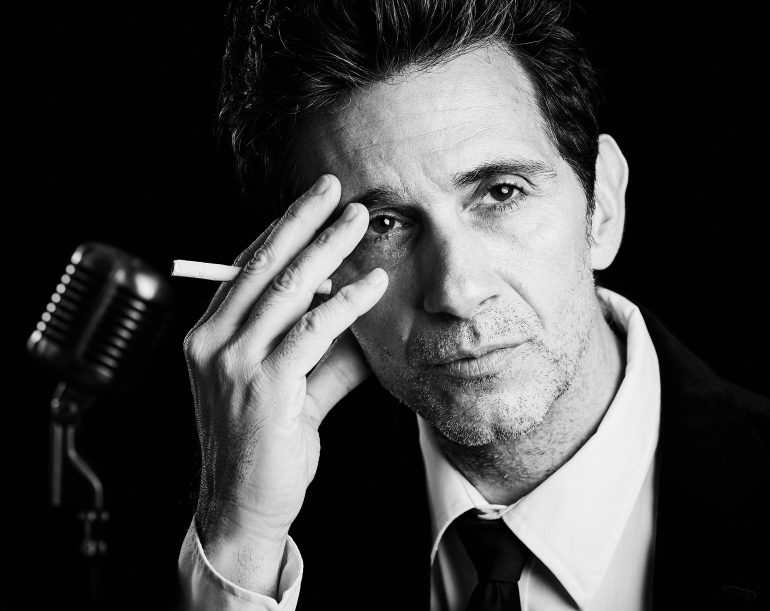

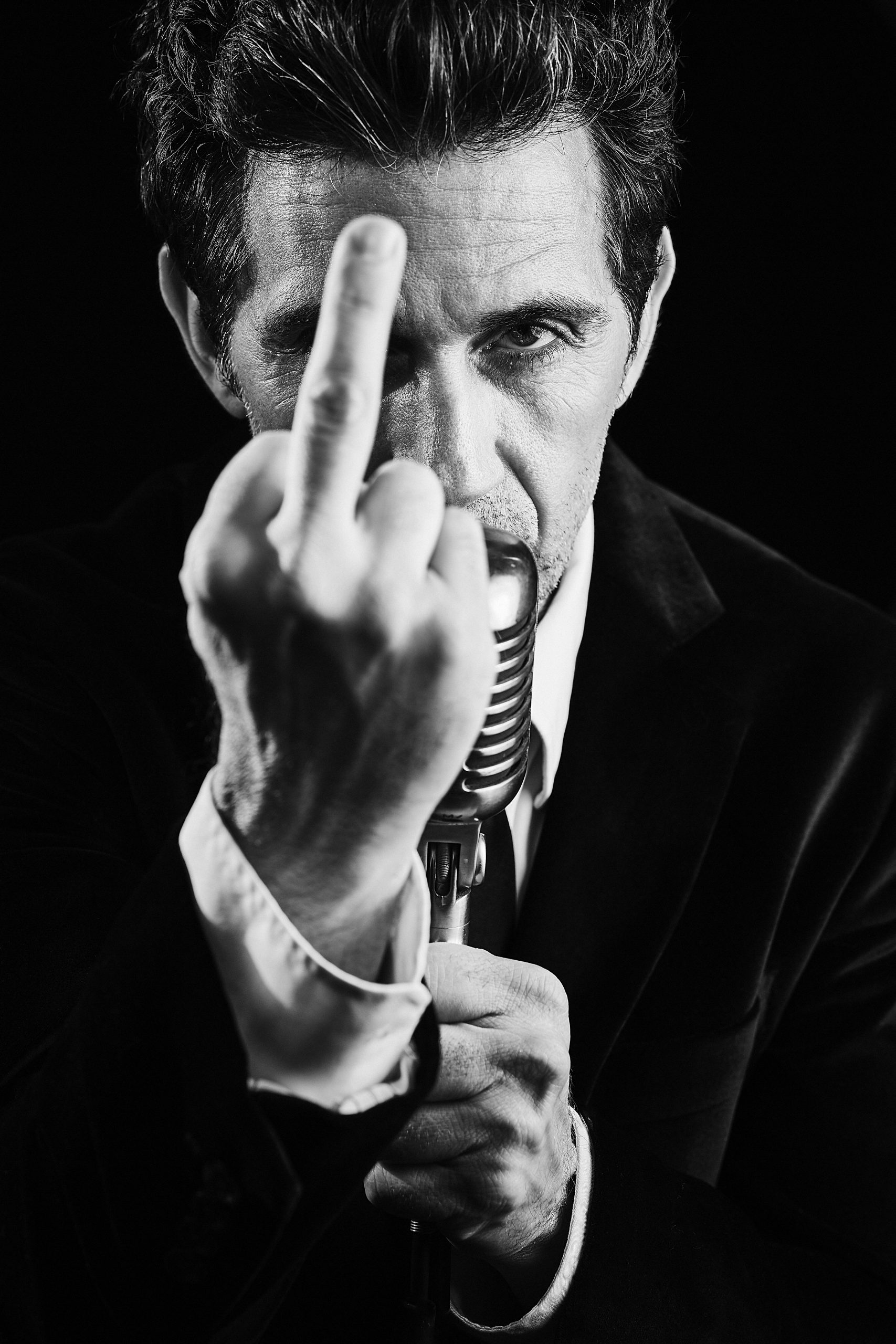

For those not familiar with this comedic legend, veteran TV and film actor Ronnie Marmo re-enacts Bruce’s short, tragic life (1925-1966) in a one-man show he wrote called I’m Not a Comedian…I’m Lenny Bruce.

The show, which is playing through February 16 at the Royal George Theatre, is directed by Chicago native, actor Joe Mantegna.

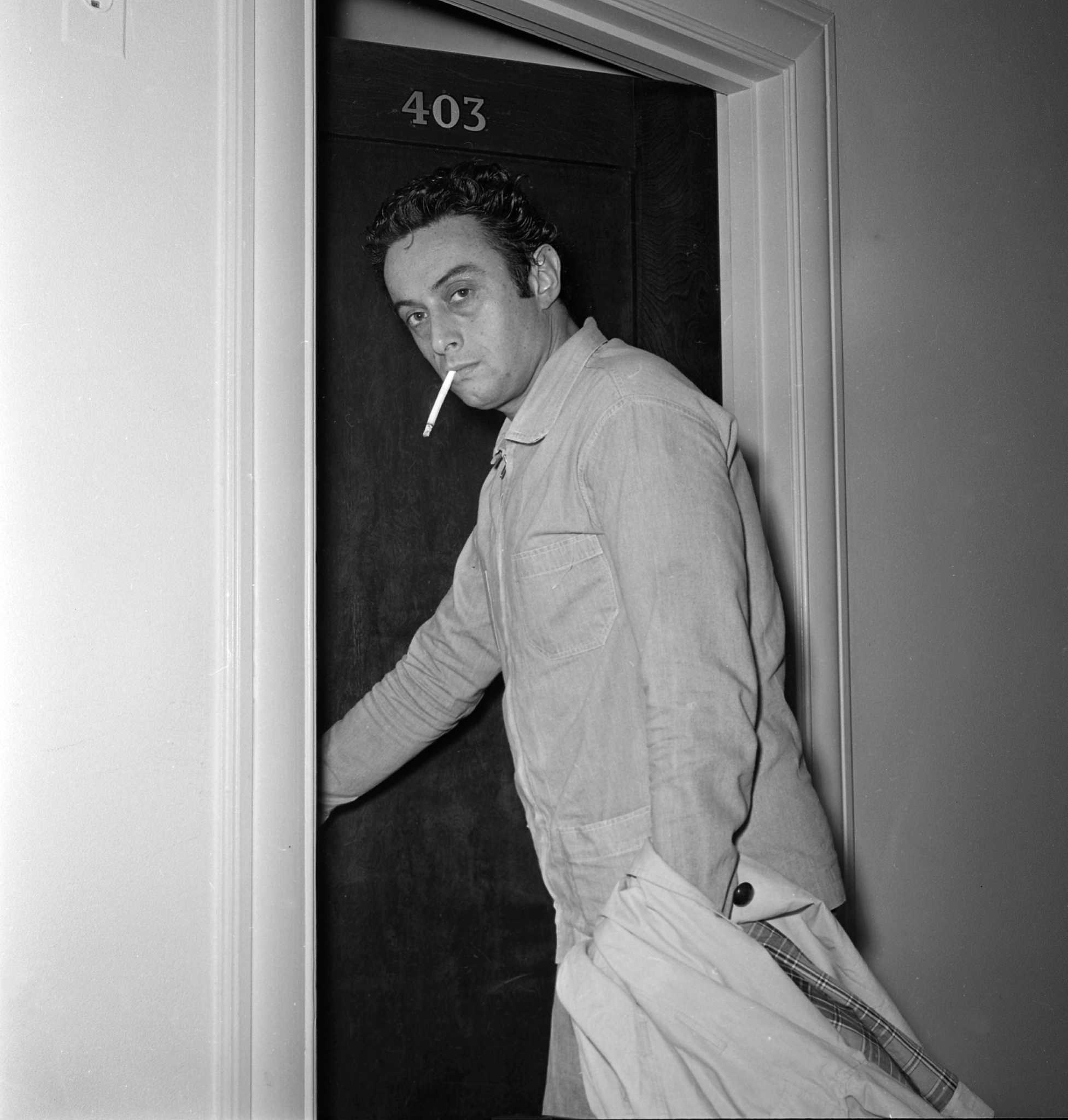

More social critic than funnyman, Bruce rose to fame from the early 1950s to the mid-1960s, sharpening his acerbic wit on the nightclub circuit and later in larger venues like Carnegie Hall.

Flaunting his characteristic spoken-word style, described as resembling the cadence of a jazz musician, Bruce skewered the establishment, frequently making religious leaders the target of his ire. He was fearless in his appraisal of society’s sacred cows. Race, religion, politics, sex – no subject proved off limits to him.

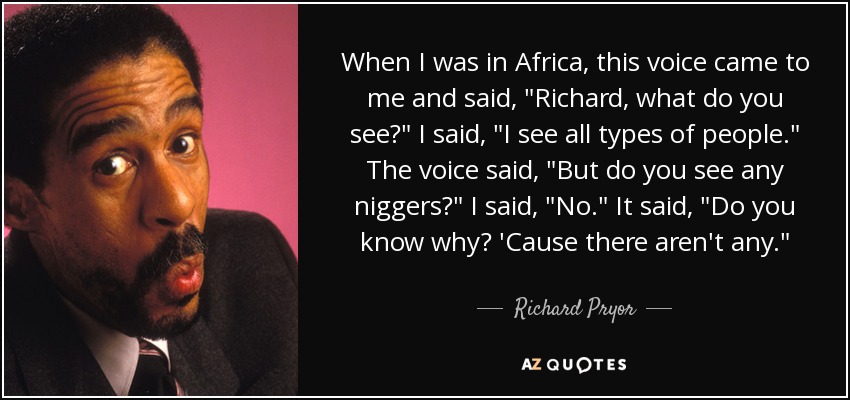

Dick Gregory, the comic and Civil Rights activist, regarded Bruce among the top three in his Mount Rushmore of comedians, which also included Mark Twain and Richard Pryor. Gregory appreciated Bruce not only as a champion of free speech, but specifically for what his stance meant to those working in the Civil Rights Movement.

“My dad was advocating for Lenny (and) for Malcolm, for Martin…to be able to say what they wanted to say…and not be killed for it. Or not make it criminal for them to say their truth,” said Gregory’s son Christian.

No doubt the comedy scene would present a very different climate today had Bruce not suffered for his art. Beginning in 1961, he was plagued by numerous arrests at the hands of authorities accusing him of onstage obscenity.

In retrospect, his fight for free speech furthered the First Amendment debate and arguably defined our present cultural standards. But it did so at great financial and emotional toll on Bruce.

Refused entry into the United Kingdom and banned in many major U.S. cities, his prospects dwindled to such an extent that by 1965, the only town he could book a gig in was San Francisco.

The night I attended Marmo’s performance at the Royal George Theatre, I met 87-year-old Lionel Cohen from Gary, Indiana, who’d witnessed Bruce’s biting humor firsthand – if memory serves him correctly – at the London House in Chicago, circa 1960.

Admittedly, Cohen said, he showed up to the Royal George fully expecting to hear jokes, but then quickly “realized the seriousness of it” once Marmo began setting the stage.

The play opens with Marmo sitting buck naked on the toilet portraying Bruce after he’s just died in his Hollywood Hills home from a drug overdose. As a deceased Lenny, Marmo contemplates Bruce’s downfall while masterfully infusing the lighter moments, aided by some of his more famous skits.

Those include most notably the “blah, blah, blah” and “nigger” routines, the latter being a personal favorite of Dick Gregory’s. As someone deeply hurt by the term while growing up in segregated St. Louis, he found kinship in Bruce’s shared mission to (in Gregory’s words) “defang” the slur.

“Lenny could’ve simply tweaked his routine a little bit to not agitate,” Christian Gregory said. “He would’ve gone on to live a very comfortable life. But he chose not to, for principle. We don’t have enough people like him.”

N’DIGO chatted with Marmo recently to get his take on Bruce and the production.

N’DIGO: Why do you think it’s important to tell Lenny Bruce’s story?

Ronnie Marmo: I feel like the PC (politically correct) culture we’re in right now, the time we’re in, I feel like we’re regressing. People are so afraid, except for Dave Chappelle. Outside of him, the rest of the world, the rest of the country, seems afraid.

But I’m not going to do that. I’m not going to allow this PC culture to completely take away what I like, what I want to do. And I feel like Lenny has become the voice of so many. I’ve been doing this show for two years.

This was my 240th performance, and I can’t tell you how many people come up and say, “Thank you. We needed his voice. Thanks for speaking for us,” which is why I do all the bits, even the scary bit that I do, you know, the n-word and all that. I wanted to do all of it.

It didn’t bother me.

You got it, right?

Well, the word has never bothered me. Not really. I’ve been called it once, but it doesn’t affect me because it’s really the other person.

Giving it the power. No, it’s them completely.

Yeah, exactly.

I have had zero resistance to the word, zero. But it was scary to do. I was nervous, I’m not going to lie. But it’s turned out okay. Everyone seems to get it, and I appreciate it.

I did this performance in New York and there was this young Black woman; she’s 33. I’m doing the n-word bit, and during the bit, she gets up, she’s clapping, she’s applauding, she’s hooting and hollering.

Usually, people just kind of get quiet. Some Black people, they laugh. But she was crazy! And I was like, “Oh, my God,” so I literally went to her table and I’m like, “I love you. I love you. I’m in love with you.”

And then she later explained why she thinks it’s funny. She’s a camp counselor to inner-city kids who’ve never been to the theater. And I said, “Hey, why don’t you bring them all down as my guests.”

There was a dozen of them, all young African Americans, 15 years old, 16. So she brings them. I do the show. I do the bit. And after the show, I say to one of the kids, “So what do you think of the show?” And she’s deep, this kid. She’s 16 and a poet. She’s deep.

I ask, “What about the n-word? What did you think about it?” because I always ask. She goes, “Well, I got Lenny. I loved it. I have no problem with it. I appreciate him. But here’s the thing: That’s our word, and I don’t want to share that word with white people.”

And so here is my friend Tia, who’s crazy. She says, “Oh, my God. I’ve been trying to figure out how I felt for 30 years. You’ve just summed it up!” But then you have someone like Richard Pryor.

I don’t know if you remember that great moment when he went to Africa and came back saying, “I’ve been wrong. I’m never calling a Black man the n-word again. Ever.” He’s like, “I don’t want to use the word because we aren’t that.”

It’s really interesting. What I love about this show and, specifically, that bit, is that there’s so much to talk about, and this conversation is real. It’s not like you go see the play, go home, and that’s the end of it. This thing goes on.

You performed another play about Lenny Bruce earlier called Lenny Bruce Is Back (and Boy Is He Pissed). Talk about that and how it’s evolved to the character that you’re portraying today.

Charlie Brill is a comic who was around back then. He brought me this play and said, “Sam Bobrick wrote a play for me, but I’m too old to learn all these lines. Why don’t you do it? You remind me of Lenny.” When I read the play I was really intimidated because I thought, “Well, I know who Lenny Bruce was, but all his friends are still alive. They’re going to come.”

I was freaking out, but Charlie eventually talked me into it. Once I really started to do a deep dive into Lenny, I was like, “Oh, my God, I love this guy and I get it.”

There are so many things as an actor that you hope happen. It’s hard to manifest sometimes, but like his love for his mom, my love for my mom, his love for his daughter, my love for my daughters – so many things. He never found recovery. I did; I’ve been in recovery a long time.

So, there were so many like things about our relationship, between Lenny and I, that I fell in love. Well, I went on to do the play, fell in love with (portraying) Lenny, got great reviews, but then realized that the play was just scratching the surface.

I wanted to tell all of it because in that play we weren’t doing his bits. The playwright didn’t have the rights to the bits, so we were just talking about the material. It was much safer. But then I set off to write my own version, which is what you saw here. And I wanted to show all of it – the good, the bad, the scary, all of it.

How did you pitch this to Lenny’s daughter, Kitty? What was that process?

You know, it was funny. We had this relationship where she had heard about me and, of course, I knew about her. But we never met. Then over time, I eventually flew from L.A. to Pennsylvania to meet and take her to lunch. I said, “I just wanted you to see my face. I want you to know who I am.”

And we kind of fell in love, you know? It took years and years to get her blessing. It didn’t happen overnight. But she was here last night. She wrote me a long text and at the end, she said, “The best thing I ever did was to get out of the way and just trust.”

Ultimately, that was like a 10-year journey to get that trust. She knows I’m a good guy, authentic. I clearly love her dad. You could probably tell from the performance, but I didn’t want to do another bitter, angry interpretation of Lenny Bruce. I wanted to tell all of it.

Conducting your research, what was the most surprising thing you found out about him? Is there some obscure fact that we wouldn’t necessarily know?

I’d say 30 percent of this play is just personal information that you’ll never find on Google, maybe more. Most people think of Lenny as the foul- mouthed, bitter comic who was very unhappy.

What I discovered was his love for his mother, his love for his daughter, and his love for his ex-wife, Kitty’s mother Honey. What a charming, gentle, sensitive, funny man he was. But nobody ever portrays him that way. What I discovered was his human side.

How did he evolve from being a relatively benign type of comedian? What morphed in his life that made him want to do the type of comedy he ultimately ended up doing?

I can’t answer that perfectly. When he started, he was doing imitations only. He was doing James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart. He was great at imitations. Then one day, he was doing a show at some dive with a jazz band. He turned around and just started telling stories to the band about his life. And they were laughing.

Then he turned around to the audience and started talking. He was one of the first people to do “blue” material and personal material. Redd Foxx and these guys were doing some underground stuff. But Lenny just found his voice. He wanted to tell the truth.

Rumor has it, from his attorney that I spoke to, that it wasn’t even the curse words that got Lenny in trouble. The (government) got really mad when he did the Kennedy assassination routine. They were like, “Go arrest this guy right now.”

So, he offended everybody. There’s always that one rebel, that person who changes things, and that was him. I think he outsmarted them. Like, for instance, when I did the bit on the charades, trying to communicate that there were cops all over the room.

He would do that, and they would get so mad because he wasn’t cursing; he would put them on a string all night. And then at the end, he’d say the word (cocksucker), and then off he goes to jail.

How did you decide which skits to include? And, also, are you tailoring them if you’re in a city like Chicago, where he got arrested?

I listened to everything I could get my hands on and I thought, “This doesn’t hold up.” He had this one bit called How to Relax Your Colored Friends at Parties that he did with a jazz musician. It’s very funny and brilliant, but there are too many references that I thought nobody would get.

I went through all his bits. The ones I thought were either funny or really poignant I picked. It gave me the ability to take all the fat out, so it’s kind of like just all good comedy.

This is going to sound slightly arrogant, but a lot of people say if you find Lenny through me, as opposed to stumbling upon him on the Internet, you’ll like him much more. You’ll find him through me and then go research him because you already have context.

But if you just stumble upon Lenny, you might miss it because there’s a lot of him trying to figure out what his voice was. There was a lot of mumbling.

Anything particularly challenging in portraying the role?

Sure. We already mentioned the n-word, which makes me nervous every night. But I also understand that Lenny had good intentions. And I understood his bit.

The challenging stuff is just being able to, for 90 minutes, give my whole everything. I give over my soul every single time. I haven’t phoned in five minutes in 240 performances because the minute I do that, I’m going to stop doing this. The hardest thing is being able to just be moment to moment and fight for Lenny every night because that’s what I feel like I’m doing.