“S’up, Dog? What up doe!”

A fairly new documentary, Talking Black in America, tells the story of African-American English through interviews with linguistic scholars and conversations with everyday native speakers in an effort to better understand the historical, cultural and societal importance of African-American speech.

The documentary is the brainchild of its executive producer Dr. Walt Wolfram, a Doctor of Linguistics since 1969 and a distinguished professor at NC State University who has been studying Black speech for almost 55 years.

The film, Talking Black in America: The Story of African American Language, was produced by the Language and Life Project at NC State University, which Wolfram founded.

Talking Black in America explores how language and speech manifest in the everyday lives and experiences of African-American English speakers.

“The creativity and resilience of people living through oppression, segregation and the fight for equality, and the powerful identity forged by a shared heritage, are all expressed in the ways African Americans communicate,” Wolfram says.

“Yet, the status of African-American speech has been controversial for more than a half-century now, suffering from persistent public misunderstanding, linguistic profiling, and language-based discrimination. We wanted to address that and, on a fundamental level, make clear that understanding African-American speech is absolutely critical to understanding the way we Americans talk today.”

Talking Black in America follows the unique circumstances of the descendants of American slaves as they have used language as legacy, identity, and triumph over adversity.

Over three years, Wolfram and his team of researchers traveled the nation talking to people in cities such as Chicago, Detroit, New York, Charleston, Oakland, Atlanta, Detroit, even the Caribbean, for the documentary.

“We also went to rural Mississippi because a lot of African-American speech in Northern cities is derived from the South,” Wolfram says. “So if we’re going to look at Detroit and Chicago, then we have to look at the rural South” because millions of African Americans left Southern states like Mississippi for Northern, Midwestern and Western cities during the Great Migration in the 20th Century.

To view the Talking Black in America trailer, click here.

The film features conversations with Rev. Jeremiah Wright, DJ Nabs, Professor Griff, Quest M.C.O.D.Y., Dahlia the Poet, and Nicky Sunshine, among many others. Wolfram notes that at one point in the documentary, rapper Quest M.C.O.D.Y. observes, “There are probably more people that would have been English majors or writers in hip-hop than there is in any other genre. Just from the usage of words, metaphors, similes, double entendres, triple entendres.”

“Clearly, Wolfram says, “the verbal ability of rappers and hip hop artists is a testament to the high level of verbal skill and artistic expression mastered by these performers. There is also the linguistic dexterity of everyday speakers in American society; these are skills that are learned routinely as a part of growing up in the African-American community.”

Wolfram calls Talking Black in America the first and only project of its kind. “Nobody has ever done a documentary focused solely on African-American English, which is ironic because it’s the most controversial, the most studied and the most prominent non-mainstream dialect in American English,” he says.

(Talking Black in America is available on DVD. Click here to purchase. )

The documentary was completed in 2017. Since then, it has aired on PBS stations across the country and Wolfram has toured it extensively, with screenings and discussions afterward on college campuses nationwide, including at Northeastern University of Illinois earlier this year.

Wolfram plans to expand upon the topic of African-American speech through a four-part miniseries sequel to Talking Black in America that he’s currently working on.

“I’ve been doing research on this theme for 50 years. I’ve written three or four books about it. To me, it’s like the culmination of a journey,” he says. “We’ve researched these communities, and now it’s time to give back to the communities and the public. It’s not enough if half a dozen scholars know and the general public doesn’t.”

Who And Why?

Wolfram has done much more than just study Black speech. He’s a pioneer in the field of linguistics and has published more than 20 books and 300 articles. Earlier this year, he was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, joining a roster of notable figures including Margaret Mead, Nelson Mandela, and Alexander Graham Bell.

You may also have noticed by now from the pictures in this article that the dude is white. In the following combination of interviews that Wolfram gave to the Planet Word website and to Matt Shipman at NC State’s blog The Abstract, Wolfram explains more about how his documentary and how a white guy got into the area of exploring soul talk.

Question: Talking Black in America focuses on African-American speech, why it has been so important in shaping American English, and how it has been, well, vilified in many cases. You’ve been studying African-American speech for more than 50 years – what made you decide to make this film?

Dr. Walt Wolfram: Despite extensive research on African-American speech, public information about the varieties of African-American English is woefully inadequate. In fact, misinformation and myths about the nature of African-American speech are so pervasive in our society that it is akin to a modern geophysicist maintaining that the planet Earth is flat.

As a researcher, I firmly believe in the democratization of knowledge; if a researcher has knowledge, then it is worth sharing, especially with the communities that fuel our research and a public in need of authentic knowledge to counter malignant misconceptions.

What misconceptions do people have about African-American English?

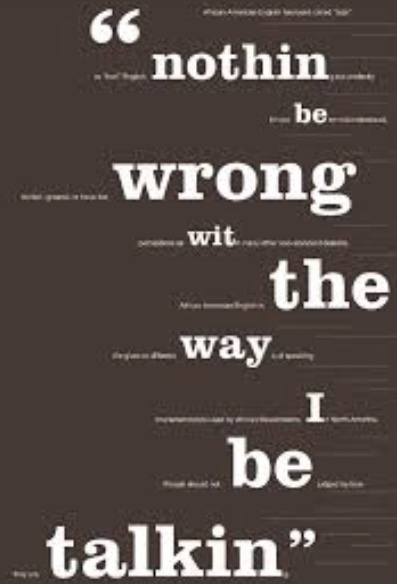

The impression that African-American language is just imperfect English or a “collection of speech errors” is probably the most widely-held misconception. To the contrary, it is highly systematic, patterned and functional.

African-American English is a unique, legitimate linguistic system that is worthy of our respect and admiration rather than ridicule and dismissal. And it has contributed more to the development of contemporary American English than any other dialect of English – in both everyday interaction and in the performance of English. The English language would be a much less vibrant and dynamic language without its distinctive contribution.

“African-American speech” is a sweeping, generalizing term, is it not?

One of the myths that has plagued the study of African-American speech is the assumption that there is a common speech pattern shared by African Americans throughout the United States regardless of where they are regionally situated.

There is as much regional, social, educational, stylistic, and individual diversity in African-American speech as there is in any of the dialects of European Americans in the United States in different regions and among different social groups. The dialects exhibit highly structured patterns that demonstrate a linguistic legacy rooted in the past and present experiences of African Americans in our society.

The history of African-American speech shows its orderly progression from a contact-based variety of English that developed in West Africa and the Caribbean during the Middle Passage to its systematic development in the rural South and its contemporary development in segregated urban enclaves of the North.

You started studying African-American speech in the Brewster-Douglass Housing Projects of Detroit in 1965. What drew you to that field of study?

As a child of immigrant parents in urban Philadelphia who spoke limited English, I developed an inclination for observing the use of language in society; it was critical for navigating my own path as a linguistic alien. My marginalized linguistic status heightened my sensitivity to the social significance of language and I studied languages and linguistics in my undergraduate and graduate school education.

But it was really the social side of language that most intrigued me, and I became one of the pioneers in a newly developing field of “sociolinguistics” in the 1960s. At the same time, my urban socialization made me quite comfortable negotiating densely populated urban areas that included a range of social classes and ethnic groups. Conducting fieldwork in Detroit – even during the Detroit riots – seemed like a natural extension of my background experience and socialization.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but how did you – a white guy from Pennsylvania – convince the African-American community in Detroit to work with you on your research?

That’s a good question, and there is no easy answer given the racialization of our society. However, a couple circumstances were on my side. First, my own experiences in a working-class community in an urban area was an asset for working in a city like Detroit.

Second, my background in athletics gave me some credibility. As an all-city basketball and football player in Philadelphia who played these sports in college, I had some street cred. With teenagers, I’d hang out on the basketball court, play in pick-up games, and then ask them for an interview.

In fact, one of my favorite, admittedly self-aggrandizing, quotes about establishing fieldwork rapport comes from a teenaged interviewee from East Harlem, who said, “I seen you shootin’ all them balls in and see how you can dribble and all, I thought you played pro basketball.” That kind of perception was helpful in the youth community where athletic ability was social capital.

Finally, I have always felt that honest sincerity, authenticity and humility help transcend social barriers if given a chance. I like people and love engaging them. Actually, I have always felt more comfortable interacting with ordinary people in working-class communities than I have with erudite scholars in academic settings.

That’s where I come from and it remains an important part of who I am; in fact, I consider myself an “accidental academic” who would have been just as comfortable as a community worker or athletic coach as I am as an academic.

At the same time, I fully realize that a single person cannot do justice to the topic of African-American speech. An engaged group of the top black and white scholars on African-American speech serve as associate producers for the film, so this documentary is truly a collaborative team effort.

Why is it important for people to understand where speech patterns come from or how they shape the way we communicate with each other?

Speech patterns are as integral to culture, history and society as any physical, cultural or historical artifact. These patterns reflect the past, present and future of African Americans in society. Unfortunately, language is typically invisible or erased when we examine the cultural heritage of African Americans.

Language is central to understanding communities, culture and communicative traditions, so how can we understand the experience of African Americans without understanding the unique, historical and contemporary development of African American language?

(For more information on Dr. Wolfram and the Talking Black In America project, click on the website here)