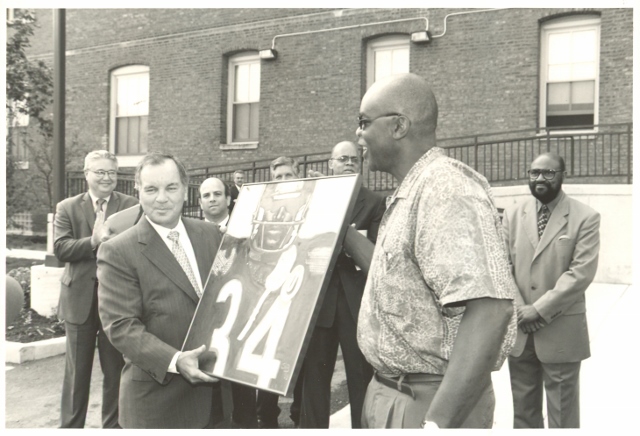

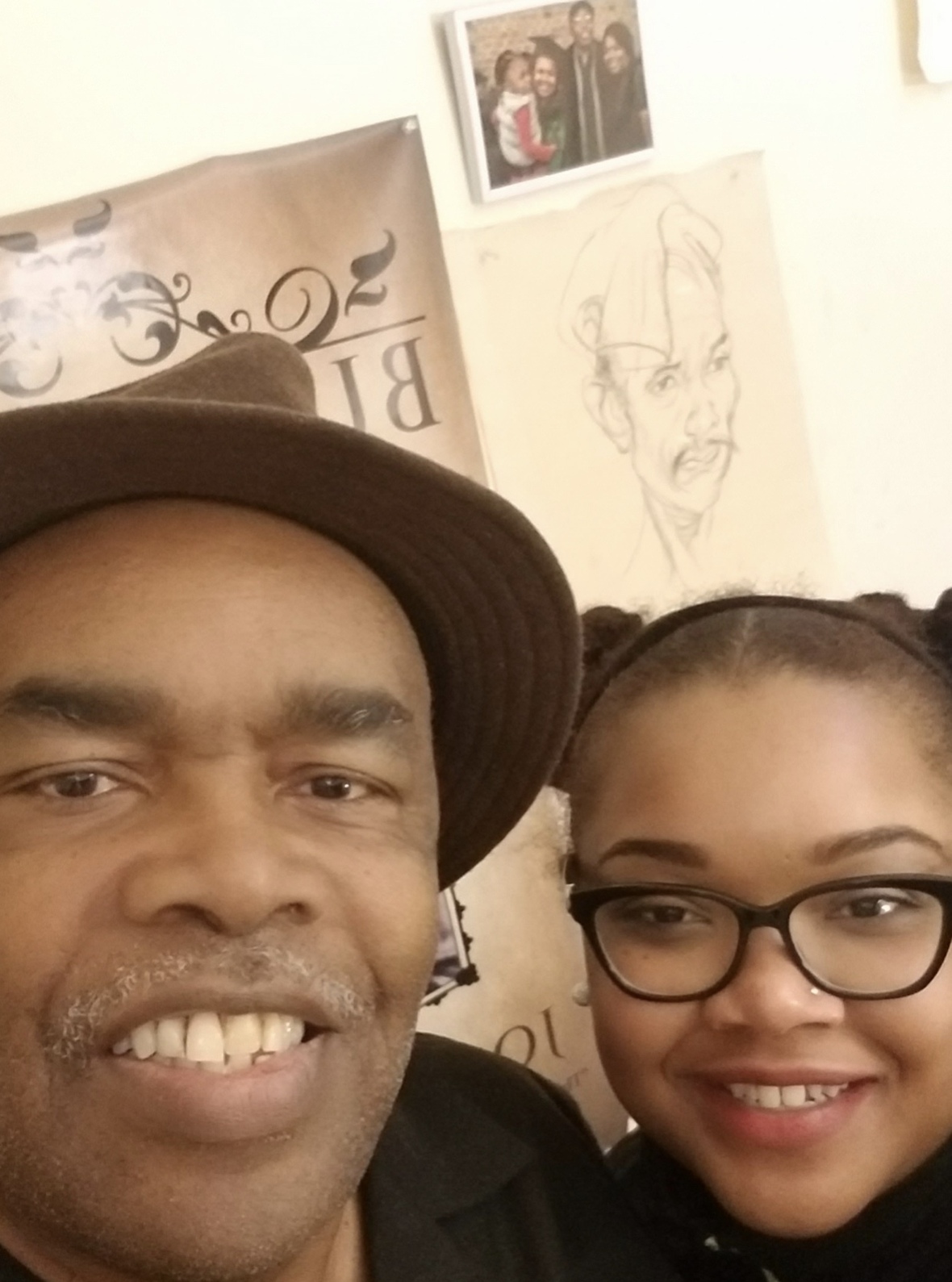

John Sibley is an author of eight books and an artist with over 100 paintings to his credit who counts Walter Payton, Mayor Richard Daley, Mike Tyson, basketball player John Salley and the South Side Community Art Center as some of the collectors of his art work.

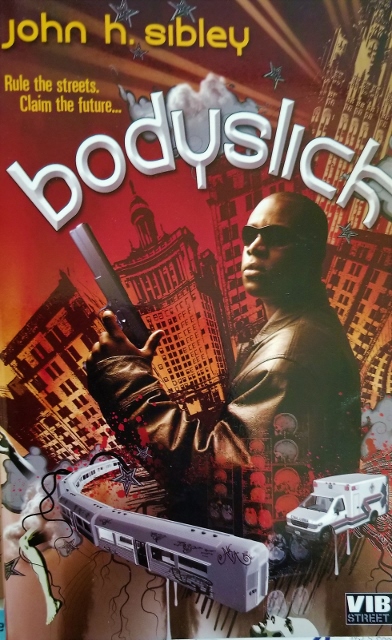

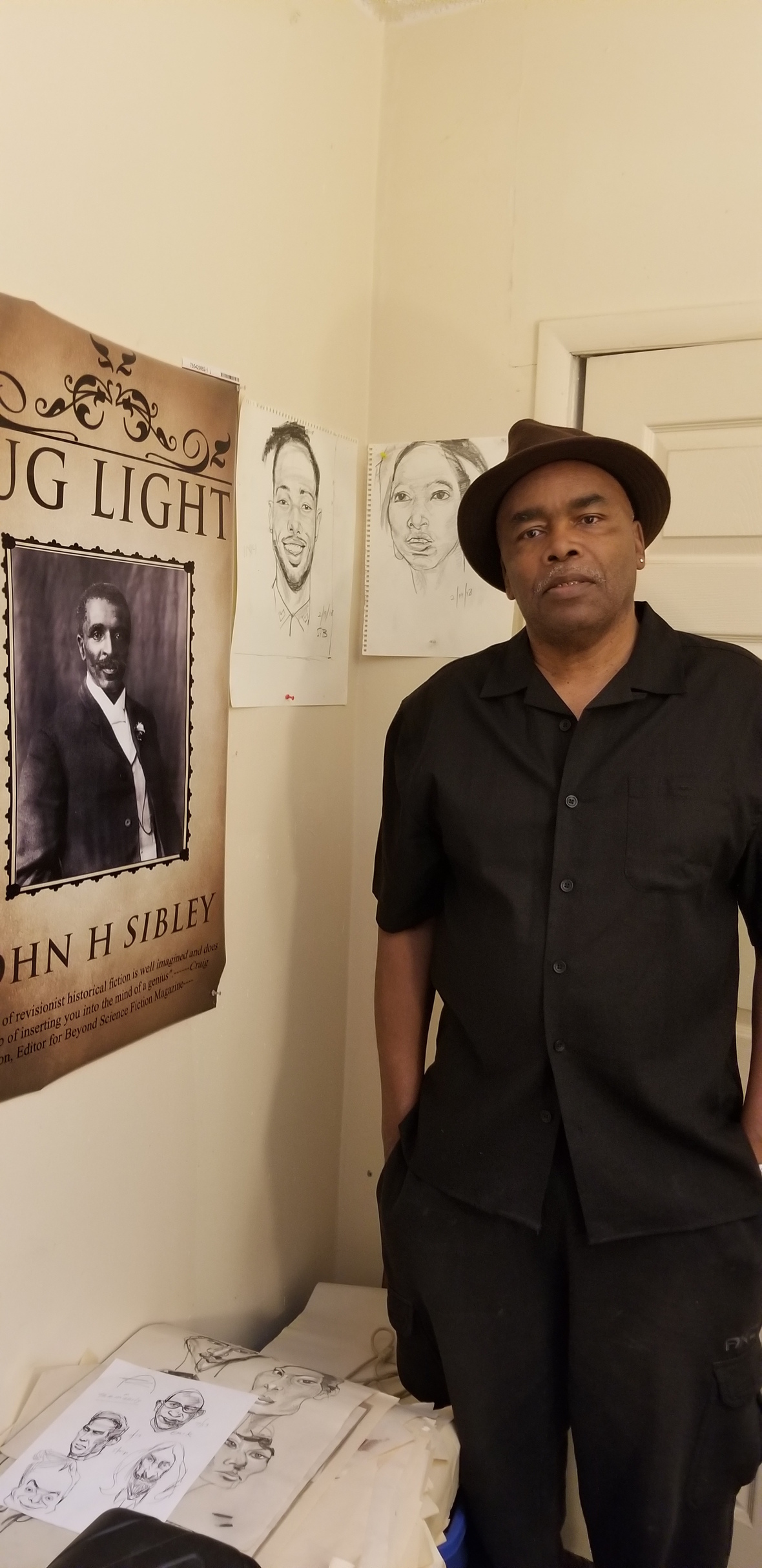

Sibley’s first book, Bodyslick, is a sci-fi novel about harvesting body parts in the Black community, among other things. His latest tome is called Riding The A-Train With Einstein. Sibley is also a Vietnam vet, an advocate for the homeless, and a bit of a Renaissance man.

We chatted recently with John about his life and work.

N’DIGO: Background, please.

John Sibley: I grew up on Chicago’s West Side, South Side and in Robbins, Illinois. Graduated from Eisenhower High School and raised in a blue-collar household. My father was a factory foreman and my mother a classic 1950’s housewife.

We lived in the LeClaire Courts projects on the Southwest Side. My father played boogie woogie on his Grand Steinway piano and was offered a gig with the Count Basie band, but he opted to marry my mother and raise a family.

We moved to Robbins because it was close to his job. He was a foreman at a plastics company. The poverty I saw in those Black West and South side communities shaped and molded how I looked at the world. I started to view Black communities with a more political consciousness. I started to view them as if they were colonies.

I moved to Aurora later in life because of a job opportunity – I worked 27 years in the private sector as a supervisor for an acoustic company. It was not a creative job, but nuts and bolts. My hands were like sandpaper. There is honor in work. Only in recent modern history have we become specialists.

In prior centuries, an artist could do a lot more than paint. They were architects, alchemists, engineers and scientists. All of my life accomplishments in art and writing are a product of the diversity of my life. Every job I have had. Every encounter with death. The pain of being homeless in the world. All of it contributed to my evolution as an artist and author.

Are you equal parts author and artist, or what would you say the ratio is?

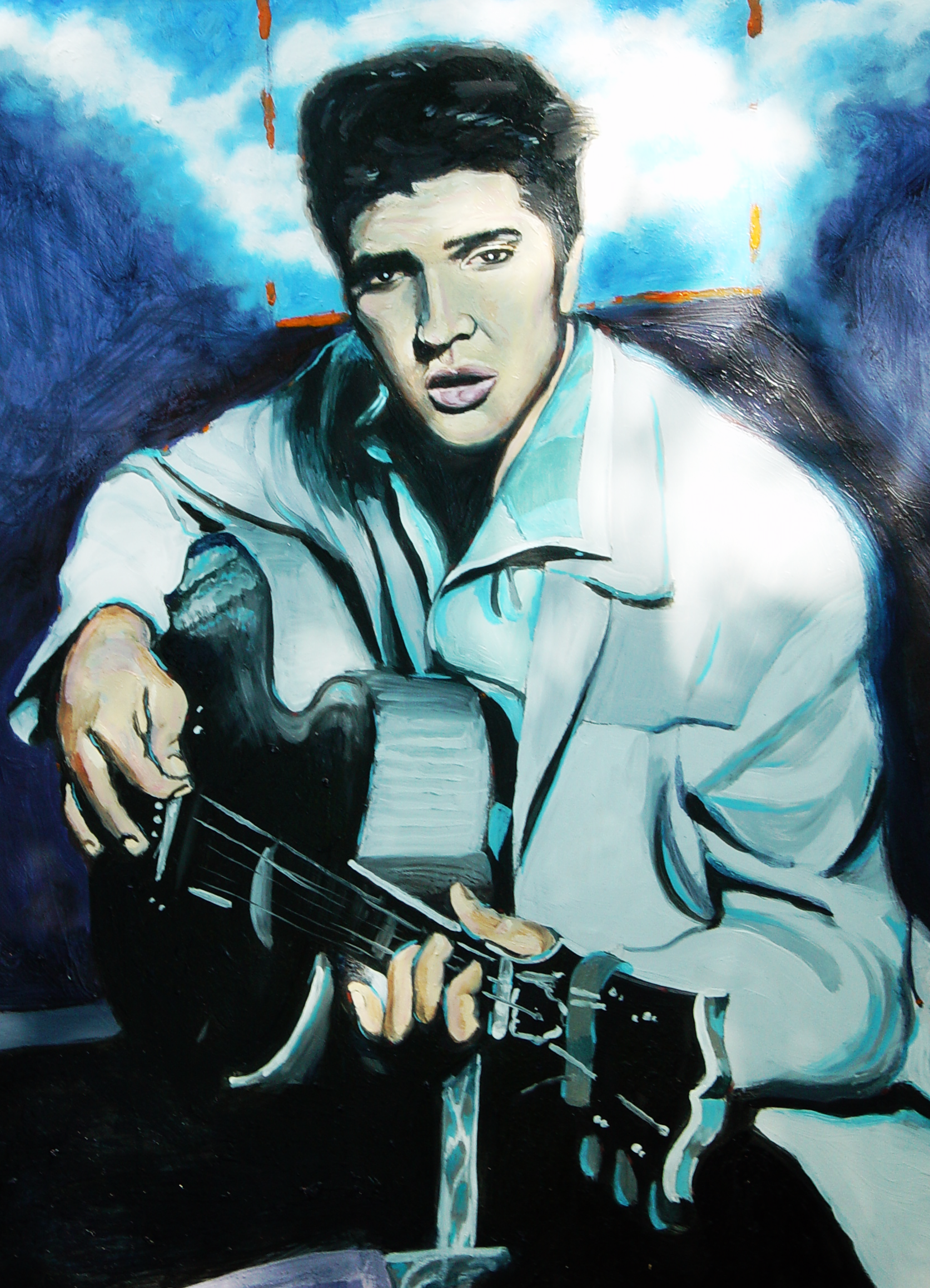

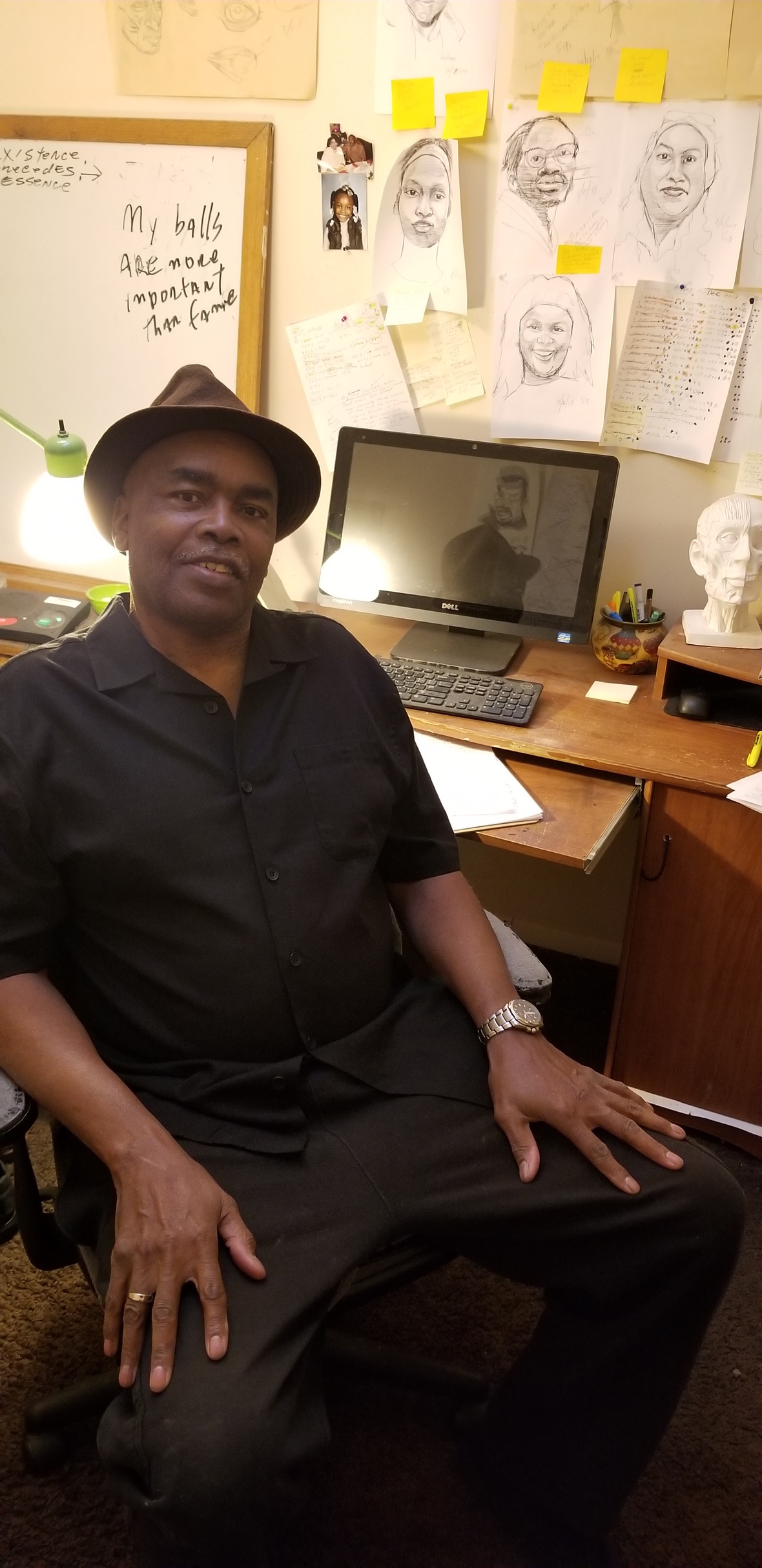

I would say 40/60 as an artist. My painting and drawing are based on a diverse range of eclectic sources. I write books because I am constantly trying to find rational and philosophical answers to questions that have obsessed me my entire life.

Writing is more cerebral than painting. It is also more accessible because all you need is a pen. You can write down a thought-experiment, but you can’t paint it. For instance: what if Abraham Lincoln had not picked racist Andrew Johnson as his vice president; would Black people have more wealth in 2019? You can’t paint that thought.

What inspires you? What do you like to write about and what are the subjects of your artwork?

Life. Just jogging in Washington Park inspires me. I gaze up thinking that this tiny blue, green-pea shaped planet would not exist without our G-type star (the sun) and if it stopped rotating on its axis at a thousand miles per hour, for just one second, all life on this planet would be destroyed. That is why I believe in a Creator that creates ex nihilo, out of nothing. I am seeking universal truth.

Where and how in your childhood did the artistic side of you germinate?

I used to visit my cousin Levi on the West Side. He was my mentor, my inspiration. Levi, despite his poverty, had a powerful influence on me becoming an artist. He used to show me his anatomical drawings of flawless nudes, his calligraphy, his poems that conveyed the extraordinary richness and inventiveness of his artistic genius. His drawings were a mixture of surrealism, African motifs, and European formalism.

His drawings were like a holistic union between pencil and paper. He would grimace while drawing, like BB King playing his guitar. The movement of his pencil on paper was like an extension of his soul.

Because of his poverty, he would rely on bedsheets, window shades, rice paper from Chinese cleaners and cardboard, so that happenstance objects would be transformed into works of art. It was no different than a slave in the 1840s making music by whistling and beating two sticks on the ground – whatever might be at hand. Levi was no different. His art rose from the things of everyday life.

Years later, I think out of frustration and not being able to pursue his art career, he turned to crime. He was busted for armed robbery, years later became blind, and died in 2017. Levi taught me how to straddle the borders of highbrow and lowbrow culture in art and popular culture.

You went to Nam. How did that experience shape your art and your life, your worldview?

As a Vietnam-era United States Air Force vet, traveling to Southeast Asia and especially at Osan and Suwon Air Force Bases in Korea (I liked it so much I did two tours there) radically changed my cultural/political views.

Off duty, I would go off base and paint with the Korean artists in their studios. Most of them were painting portraits from photos of G.I.’s loved ones to send back home. They were brilliant technicians. They had mastered western “realism” painting techniques.

I would also paint murals in clubs that we went to off base in Suwon. The brotherhood I shared with other soldiers, especially Black ones, is something I will always cherish. Something I missed when I got discharged.

Asian culture is quite rhythmic. I was amazed at how Asian women danced with so much rhythm and syncopation to Marvin Gaye’s Mercy Mercy Me at off-base clubs, where you could drink American beer and select from the menu: dog meat, baked water bugs, and fried tarantulas and kimchee.

You went to college after the military, the Art Institute, no less. What were your life plans in getting a Fine Arts degree?

I studied at the American Academy of Art in Chicago before I enlisted in the Air Force. After my discharge, I studied drawing at Kennedy-King College, then transferred my credits to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

I was shocked when I studied there because it seemed like all the students from the wealthy, affluent suburbs embraced minimalism, conceptualism, installation art, and abstract expressionism as an easy way to say, “I am a artist” without any drawing skills. Mediocrity can no doubt be found in any art form, but its presence is rampant in the world of art.

I don’t encourage students to major in fine art. We live in a STEM driven culture. You can actually learn to draw and paint on your own or study under a professional. You should never major in art alone. Minor in art and major in business, law, technology or engineering.

How’d you make a living after you graduated?

I dropped out of art school and didn’t go back to school for a decade after I got a job years later at an acoustic company that I worked at for 27 years as a supervisor. I graduated, but I never gave up my passion for art and literature. The only reason I went back to school is because my company paid for it. I was the first in my family to get a degree, but I think I would be just as successful without it.

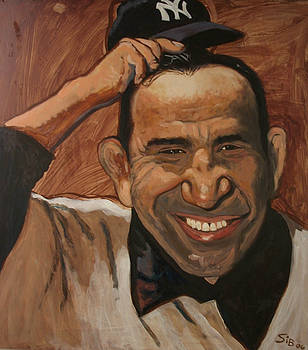

At some low point in my life, I earned my money on the streets as an itinerant street artist. I enjoyed it because a street artist only has a few minutes to capture a likeness in caricature.

It is a great way to sharpen your drawing skills and it is also performance art. More than any other kind of artistic event, it allows the audience to confront and see the creative act. The opportunity to watch the portrait artist create is obviously what draws the audience to this art form. I like doing it even now. It gets me out of the studio and into the “real” world.

You “accidentally” became a homelessness advocate and wrote a book about that. How’d that come about?

I dropped out of art school after I got busted for a crime I didn’t do. I was married at the time and that conviction turned my world upside down. It was one of the reasons I ended up homeless for six months on Chicago’s mean streets.

I wrote a book about the experience called Being and Homelessness; Notes from an Underground Artist. It was published in 2012 and a second edition printed in 2017. Here’s an excerpt from it:

“My idealism about the American Dream became a nightmare on a cold Chicago December night in the late 1970s when I was arrested for armed robbery. I didn’t commit the crime. I was walking south on 119th and Vincennes when three police cars pulled up, surrounding me and blocking my path.

“Hold up your hands and don’t move!” A white officer searched me, handcuffed me, and then made me get into the squad car.

“I haven’t done anything. What’s this about?” It took about eight minutes as they drove to an undisclosed location. They pulled me out of the car and dragged me in front of a middle-aged blond, white woman.

“Is he the one that robbed you of ten dollars?”

“Yes… he is the one.”

I had $75 on me that I was taking to my estranged wife for Christmas. It was surreal to me. I am an Air Force veteran. I served honorably during the Vietnam war. I could have died defending democracy. In my naïve world, this was a classic case of mistaken identity.

I looked like some Black guy in a fatigue coat who had robbed her. I felt so strongly about the mistaken ID charges being dropped that when I went to court I did not have a lawyer. I was incredibly naïve about the legal system at that time.

The judge gave me a continuance and I hired a lawyer. He told me that because of my poverty (I was a student at SAIC), it would be better to plead guilty and get a light sentence. I pleaded guilty and got two years probation and a felony record that scarred me for life. Even today I wonder what would have happened if I had not pleaded guilty?”

During that period, I became homeless for a while and that period of homelessness made me very pragmatic about how this capitalist system works: it’s a barbaric Darwinian world where the have-nots get devoured by the haves. An estimated 600,000 Americans are homeless every night – 30 percent of them are veterans and almost 50 percent are Black.

Homelessness taught me how fragile, fleeting, and impermanent life can be. But my main message in my book, as a homeless advocate, is that no matter what the circumstances, with faith and determination, you can still live a decent life and pursue your creative goals.

What are some of your favorite artworks done by you?

My favorites are:

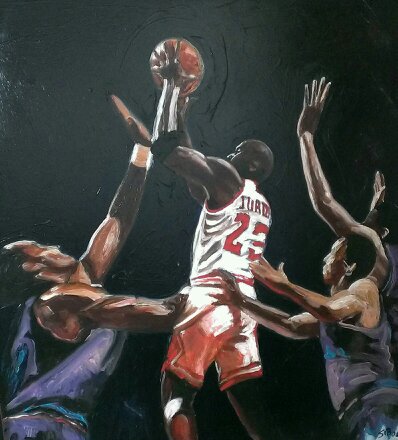

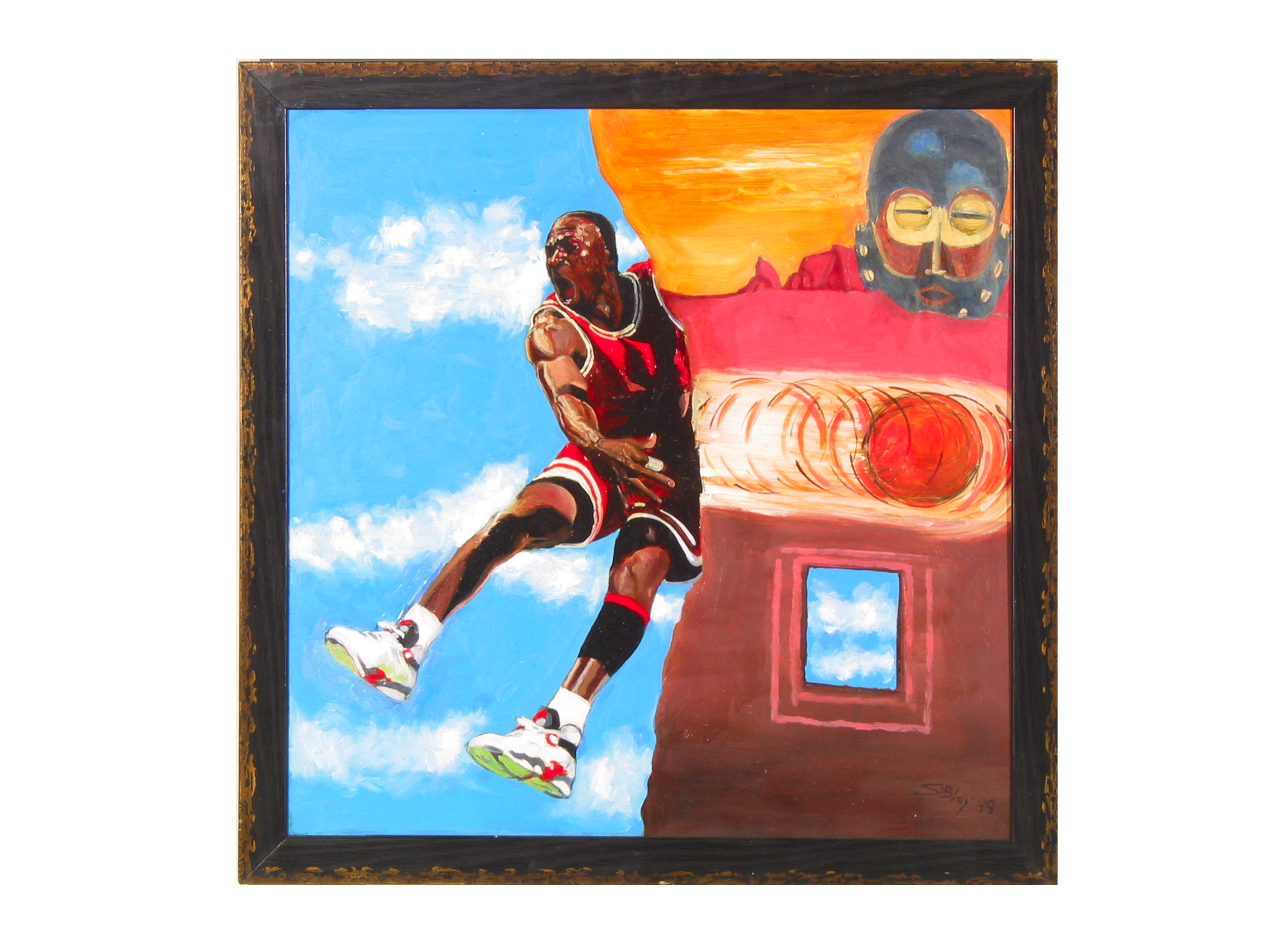

1. Michael’s Universe

2. Third World Man

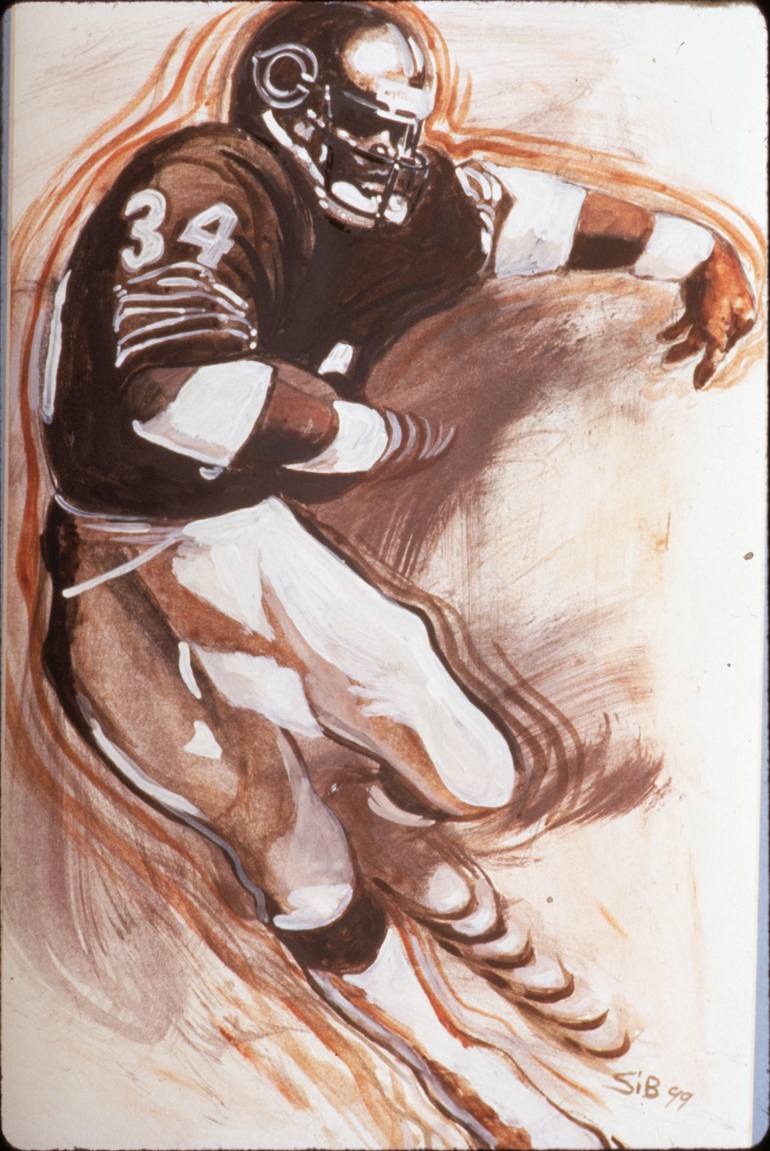

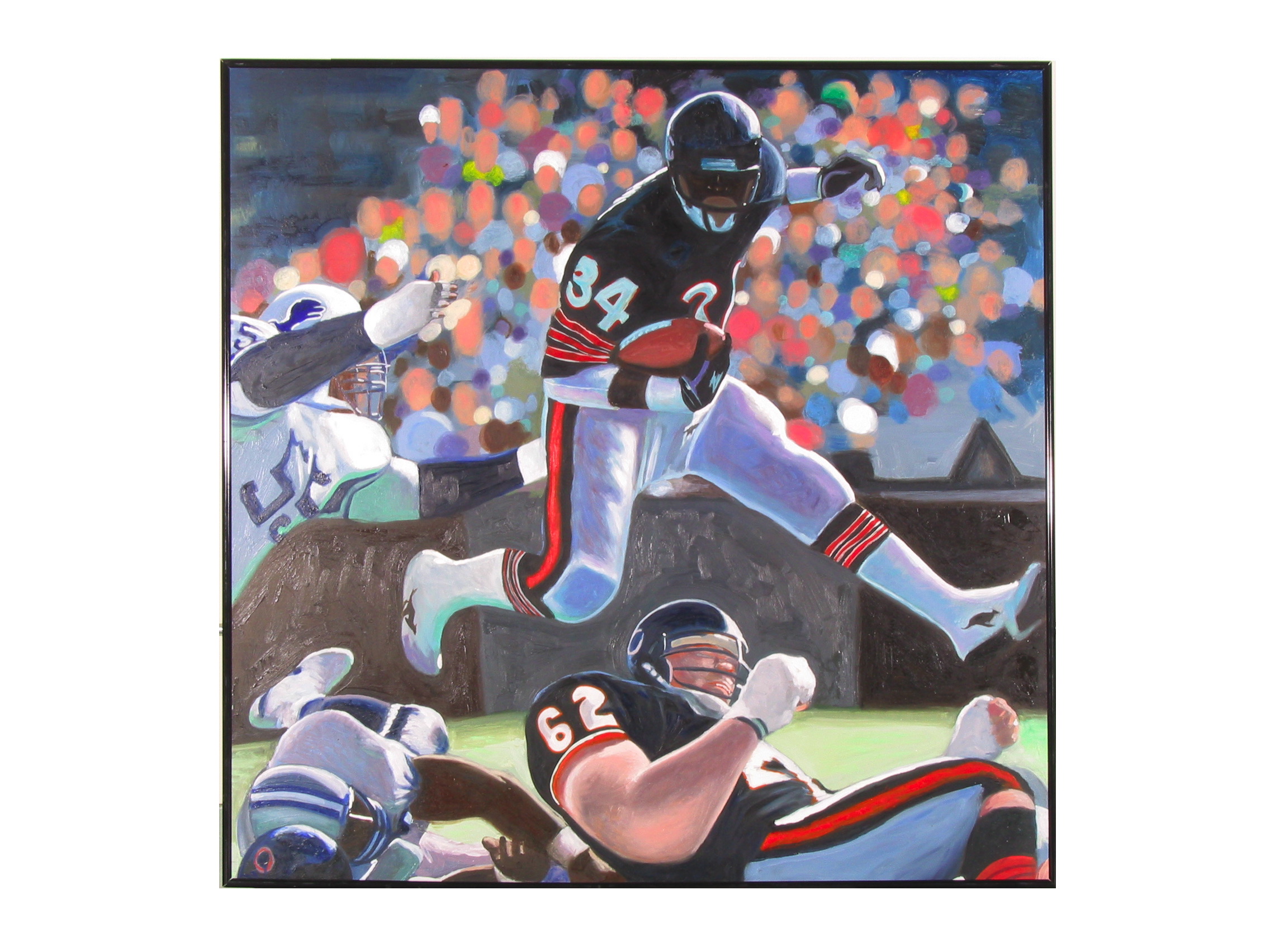

3. Sweetness

4. Travon Morte

5. String Theory

6. Trane

Who influenced you artistically?

As I stated earlier, my cousin Levi was my biggest influence in art, along with Nicolai Fechin, Caravaggio, Romare Bearden, Charles White, and Henry Ossawa Tanner. In literature, it’s Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Frantz Fanon, Cheikh Anta Diop, Robert Beck (Iceberg Slim), Chester Himes, Ralph Ellison, Robert Silverberg, Phillip K. Dick, and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Personally, who do you like to read and whose art do you like?

When I was younger I read all of Donald Goins’ Iceberg Slim books. I have Faulkner to John A. Williams. I like Salvador Dali’s surreal vision, but especially his understanding of anatomy, line, form and color. I also like Norman Rockwell, who critics consider kitsch, and Bernie Fuchs the illustrator and Andrew Wyeth, to name a few.

As an artist and author, why have you stayed in Chicago instead of being on one of the coasts?

I love Chicago. I think Chicago’s lakefront is the best in the world. Chicago is home of the electrified blues. When I was a boy, my Uncle Miles would take me to Maxwell Street with him every Sunday. At its peak “Jew Town”, as they called it, attracted 20,000 visitors each Sunday and helped furnish a living for a thousand vendors.

At an early age, I realized the vibrant beauty of Chicago and Maxwell Street. I used to do caricatures on Maxwell Street on Sundays, not just for the money, but to be drenched in the spontaneous energy of the wah,wah, wang of the blues guitarists.

Bottom line, I’m here because Chicago is my home. It doesn’t matter where you live, if you somehow re-invent the wheel, the world will eventually knock at your door.

What’s the future for you? What’s on the drawing board?

I am hoping in 2020 to have a retrospective of my work and also have a book signing. I don’t have a venue yet. I am also going to work on a coffeetable book showcasing all my art. The future is to keep creating and be humble. The Creator has a master plan.

How can people access your work?

You can check out all my books at: amazon.com/author/johnsibley. My online gallery can be found at: http://www.saatchiart.com/johnsibley and http://www.artmajeur.com/johnsibley.

The contrasts in life and justice are often hard to understand. John and I were classmates in high school. Two years after he and I graduated, another friend of mine and I were involved in a stupid act that did include stealing a car. We were arrested in a South Suburb of Chicago. My friend was in the military, so the police wanted to let him go, but when he said we did it together and would not take his “free pass” out the door, the charge for both of us was reduced to Misdemeanor Petty Theft. I served a year of Probation with Cook County, but since it was charged as a misdemeanor, the conviction never seriously affected my life after that. For years, my gratitude was solely focused in my friend. But as I grew older, I realized that had i or my friend been African American, the likelihood of the “free pass” would have probably been zero and I would have a felony conviction on my record and probably would have spent time in jail. To see that John was wrongly convicted of a Felony he did not commit sadly does not surprise me, so it just made it all the more poignant to read his story and reflect on the opportunities (read “white privilege”) that I could follow because the law was bent on my behalf and my being white was an essential factor in that.

Thank you for sharing that Tom.