The National Museum of African-American History is in Chicago looking for stuff from your attic and your basement; they’re looking for history.

They are looking for your photo albums and they will digitize them for you. They are looking for your family documents and your home videos.

They will be at the DuSable Museum until September 20; at Evanston Township High School from September 21-28; and at Chicago State University from September 24-28.

The Museum’s Community Curation Program is traveling the country to encourage preservation and intergenerational story telling throughout the African-American community.

Think about your possessions. Think about your things that belonged to a parent or a grandparent that you may have ignored. Collectors realize the value and significance of the materials that you might not hold in high regard and even consider junk.

For example, you might have a ticket to a Jackie Robinson baseball game, or a program from a stage show at the Regal Theater, or a yearbook from high school. You might have pictures from a Motown show.

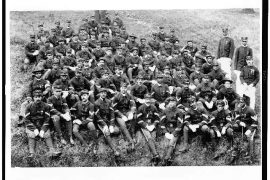

You may have a program from a Bulls game when Michael Jordan played or from the Bears when Walter Payton played. You might have a program from a Civil Rights event that changed history. Maybe you have pictures of your granddad, dad or uncle in his World War II army uniform. Maybe you have photos of yourself dancing on Soul Train.

There is a quiet movement going on in the Black community to hold on to and to record our papers – that means letters, writings, programs, photos, documents, books, memorabilia and the like. We have to tell the story of our authentic selves. There is so much to note about our history that is not always reported in newspapers or magazines.

For the past six months, I have gone through the 28 years of N’DIGO printed papers and have completed the first phase of my donation. That involved giving hard copies of the paper to the Carter Woodson Library and the Chicago Historical Society.

I wrote about it on our ndigo.com website and Facebook and have received several phone calls and emails asking how to do it. I am no expert by any means, but I will share tips on what I have learned from my experience.

I will begin by telling you that it is an overwhelming experience and you really have to think about it before you begin. But just do it. Just start.

1. Decide before you begin to dispose of your materials where you want to donate. You might think of your college, the DuSable Museum, the Carter Woodson Library, the Chicago Historical Society and the like.

After you make that decision, call that institution and have a conversation or meeting on what’s important and how to make the donation. I promise you they will think of things that you won’t.

My father was the first African-American Pepsi-Cola distributor. As a child, I remember the various signs that reflect logo changes of Pepsi. I remember one Saturday, my Dad and I went through years of Pepsi promo material. We tossed the signs. I wish I had those signs today.

2. Get someone to help you. It’s not an easy process. It’s tedious and it is emotional as you remember and relive some situations and remember people who have passed. It is challenging to your memory and reflections.

I know my mother’s pictures, as does most of our family. Her pictures are of entertainers of her era like Count Basie, Joe Louis, Lena Horne and other famous folk who played at the club where she worked. Her stories will long be remembered; we know when and where they were taken.

3. Have a strategy and give yourself time for the project. Schedule your time. Put your piles in order. I found working in four-hour intervals was perfect. Depending on how much stuff you have, it takes considerable time to gather material on your own, before it is ready for actual donation. Stick with it and maintain your schedule. I did my work on Thursday afternoons from 1 to 4.

4. If you are donating pictures, be able to identify by name, year and occasion. If you can’t identify all parties, identify the major people. Describe what the event was.

I have written speeches for people over the years and put on major events. I kept materials like tapes, videos, CDs, etc. in boxes with the event or the person’s name.

When Mrs. Cook from Carter Woodson Library visited with me, I shared with her one of the boxes. I don’t remember what’s in the box, but as I open it, I know what’s there.

We opened the box labeled “Harold Washington” and the first thing we saw was a tape of Harold Washington’s funeral. I coordinated his funeral at Christ Universal Temple. Mrs. Cook said she had never seen the tape before.

5. If you have supportive materials for an event, like a program or invitation, share it. For example, you might have attended your church anniversary or company picnic or a social event or a sorority conference. Note the significance of the occasion and location.

6. As you sort materials, the things you place in the throw-away pile, save and share with the archivist before you toss. What you are tossing might be historically significant.

We have produced 20 N’DIGO Galas and entertainers like Ray Charles, Natalie Cole, and Nancy Wilson, who performed at the Galas, have passed. Their printed invitations are valuable to the N’DIGO Gala Story.

7. Provide insight and stories on events, pictures. Tell stories about your stuff. The insight is valuable. My mother has a photo of her and my dad in New York and they are having dinner, but the look on their faces is very pensive. The waiter had just told them that President Roosevelt had died.

My mother remembers his exact words: “I regret to inform you that our President has died.” I have that pictured labeled “The Day Roosevelt Died.” She remembers where they were at the time. She considers Roosevelt the best President of her lifetime.

8. Determine how you will dispose of your materials. You might box your stuff; the institution might have a particular way of how they want to receive things.

9. Sign off on what you donate and share with your family. Write about what you donated so your family members, employees, and loved ones will recognize your work and where it is recorded.

Think 50 years from now after you and your peers are gone – will researchers be able to recognize your endeavors? Researchers, scholars, teachers, writers, journalists will refer to your materials to denote an era.

10. When you have completed the project, ask how the receiving institution will recognize your donation. Perhaps there will be an exhibit or a party.

And finally, when you are done – and I mean completed and finalized – celebrate yourself because you have recorded your very own history. It is a splendid job at the end!