Every so often I go looking through my files for an old article to see if it’s still relevant. The following column appeared in N’DIGO on June 19, 2003, after a conversation with the late journalist and historian Vernon Jarrett.

Neither one of us could understand celebrating Juneteenth. So, we agreed that he’d write a column on the 13th Amendment for the Chicago Defender and I’d write about the celebration. Vernon died the following year. He never mentioned his birthday was June 19 (1918).

Why Are We Celebrating Juneteenth?

I like holidays and celebrations as much as the next person, but I do not understand the growing popularity of Juneteenth.

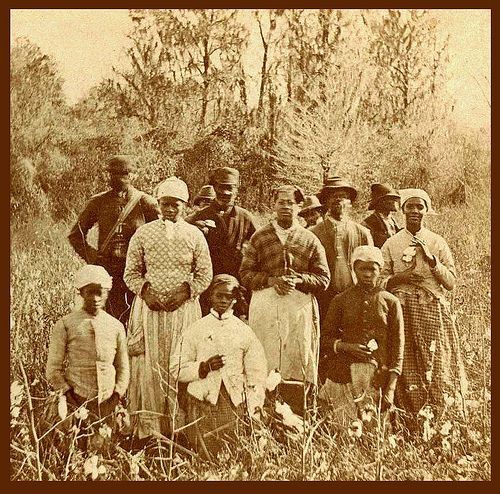

I understand trying to find something about slavery to celebrate and/or romanticize. As an African American, I also understand the need to try and make sense of one of the most diabolical institutions in our nation’s history.

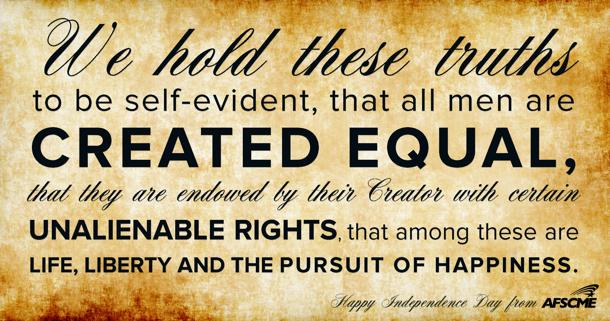

After all, this country was founded on the proposition of freedom. Yet, the framers of the Constitution, United States’ presidents, and churches of almost every denomination supported slavery as an acceptable institution.

I understand that as we move farther away from the vestiges of slavery, there is a need to hang on to it, so that revisionists will not rewrite the history of Africans in America. Juneteenth, however, is just one more travesty of slavery.

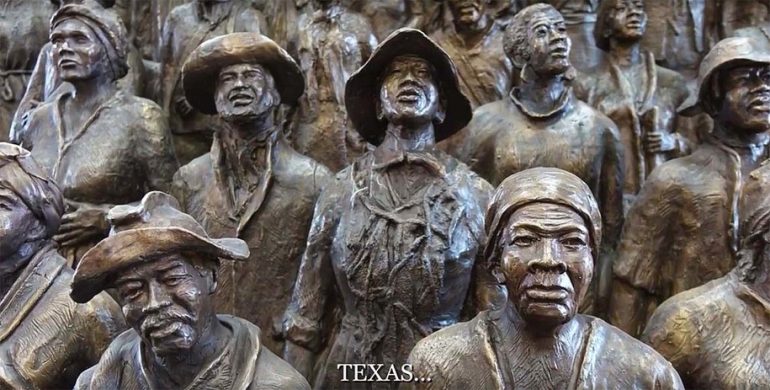

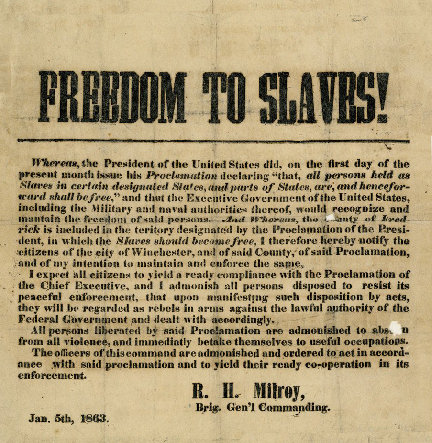

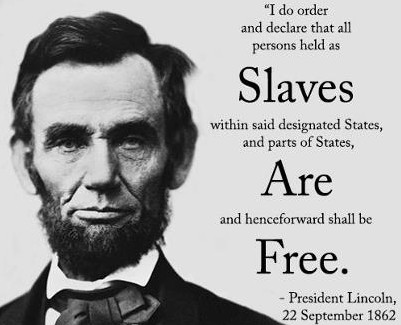

More than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation became law on January 1, 1863, Texas slaves learned they were free. Their owners knew, but withheld the information. There were no radio or television newscasts, or newspapers to read (or social media to look at). Even if there were, it was against the law for blacks to read.

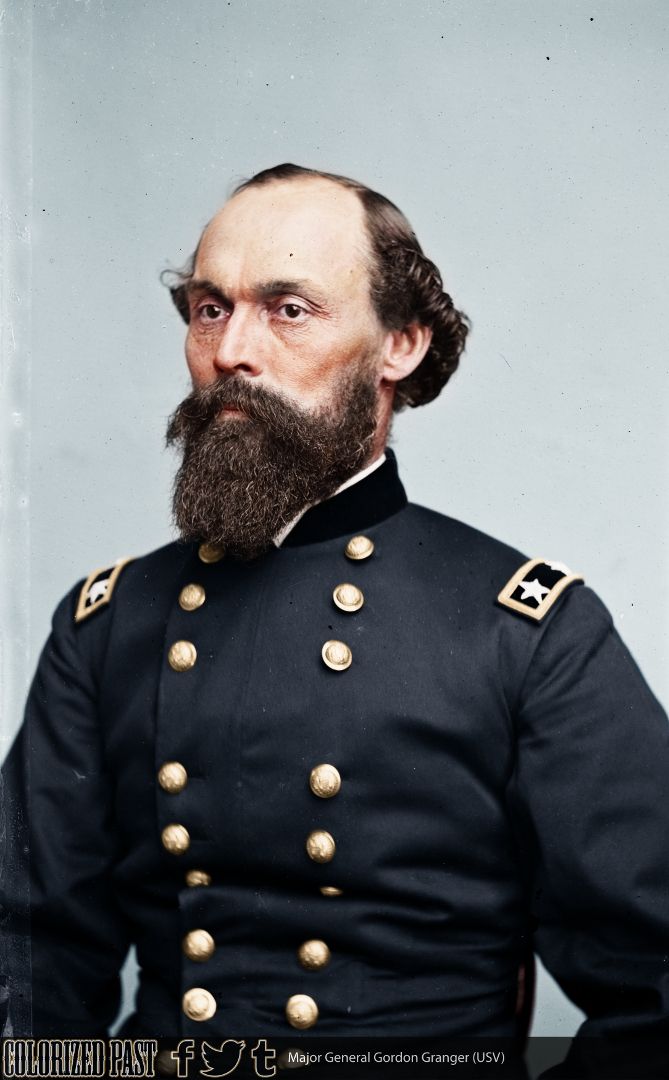

So, it was not until General Gordon Granger – the only name associated with Juneteenth –arrived in Galveston, Texas, (along with 2,000 federal troops) and read General Order Number 3 aloud, that slaves learned they were free.

On June 19, 1865, Granger gathered a crowd in front of the Osterman Building at 22nd and Strand and said, “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and free laborer.”

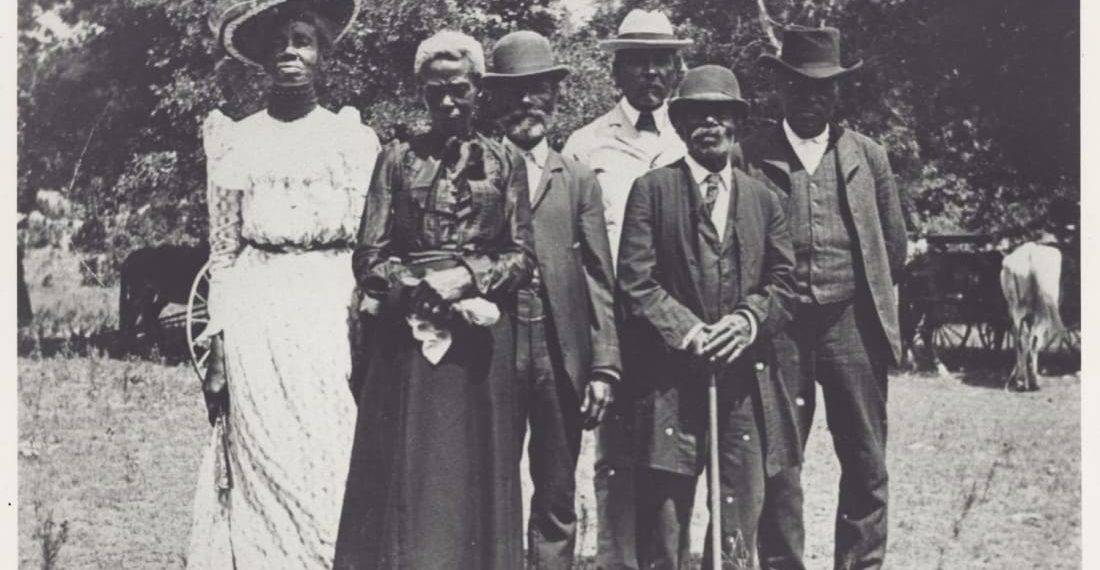

Upon hearing the news, the former slaves immediately erupted into shouts of joy and spontaneous celebrations. Consequently, in Texas, Juneteenth is considered the first recorded African American celebration. Jan. 1, 1980, Juneteenth became an official state holiday thanks to the efforts of Al Edwards, a Texas legislator.

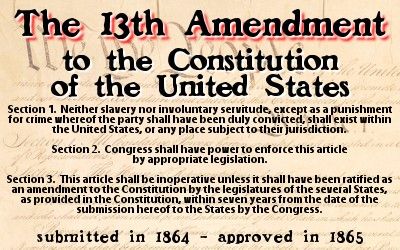

For Texas, the celebration of Juneteenth is appropriate, but it makes no sense for the rest of us. A more fitting cause to celebrate would be the ratification of the 13th Amendment Dec. 18, 1865.

Finally abolishing legalized slavery throughout the United States Section 1 states that, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Section 2 gives Congress the “power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

The 13th Amendment paved the way for Congress the pass the nation’s first Civil Rights Bill, in the summer of 1866, which gave full citizenship to blacks, along with all the rights enjoyed by other Americans. Of course that did not last long because laws could not change the hatred in men’s hearts. It would take another 100 years and the loss of thousands of lives before America would acknowledge the atrocities heaped upon black men and women.

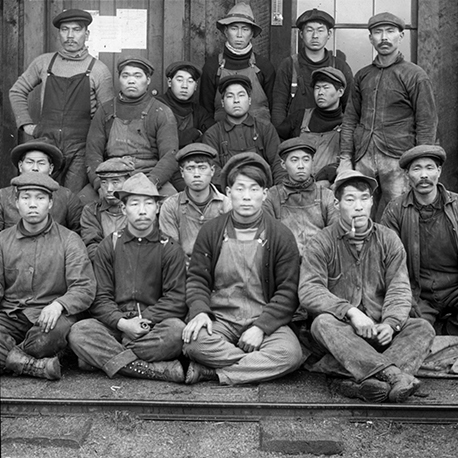

The 13th Amendment also persuaded the United States Supreme Court to extend protection against slavery to other races: “Negro slavery alone was in the mind of the Congress which proposed the thirteenth article, it forbids any other kind of slavery, now or hereafter. If Mexican peonage or the Chinese coolie labor system shall develop slavery of the Mexican or Chinese race within our territory, this amendment may safely be trusted to make it void.”

African Americans have a long history of forcing this country to be better; of fighting to open the doors of opportunity for everyone; of succeeding against the odds. We do not have to manufacture a holiday for recognition. We need only look back at our history to learn that there are a number of events we could celebrate as a nation other than being last.

Yes, America celebrates the Fourth of July, but without us the Declaration of Independence would still be a lie. Now, celebrate that!

Delmarie Cobb is a veteran journalist and political consultant and founder of The Publicity Works public affairs, political consulting and media relations firm, and of Ida’s Legacy, a political action committee dedicated to carrying on the activist ideals of the late journalist, educator, feminist, and anti-lynching civil rights leader Ida B. Wells.