Zora and Langston: A Story of Friendship and Betrayal

By Yuval Taylor

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company (March 26, 2019)

Hardcover: 304 pages, $18.27 (Amazon price)

After weeks of watching, listening and reading about Donald Trump’s travails, I was beginning to identify with Canada Bill Jones, the famed riverboat gambler who memorably uttered: “I know the game is rigged, but it’s the only game in town.” Yes, I’d been spinning in the non-stop vortex of chaotic Trump stuff.

Does this sound familiar? First it was necessary for the Democrats to win the 2018 mid-terms; then we had to wait for impeachment until the Mueller report came out; then ponder if a Special Prosecutor could indict a sitting president; or whether it’s up to Congress to impeach; and now if the White House can invoke “executive privilege” to keep the nasty stuff under wraps; and how the Roberts’ Supreme Court – now with “only a beer” Brett Kavanaugh as a justice – might rule if asked.

What to do? How to escape the Trump whirlpool?

Like a drowning man thrown a lifeline, I grabbed onto a new book by Yuval Taylor titled Zora and Langston: A Story of Friendship and Betrayal.

A work both beautiful and true, Taylor’s carefully researched account of the Harlem Renaissance and two of that Black cultural watershed’s leading lights provided the perfect antidote to my overdose of Trump Trauma.

(Nota bene: To achieve this desired effect, the book should be accompanied by a personal pledge to turn off CNN, only glance at headlines of newspapers, and ignore all forms of political punditry for one glorious week.)

Zora and Langston author Yuval Taylor is a former senior editor at Chicago Review Press. Co-author of Darkest America: Black Minstrelsy from Slavery to Hip-Hop and Faking It: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music, Taylor has also edited three volumes of African-American slave narratives.

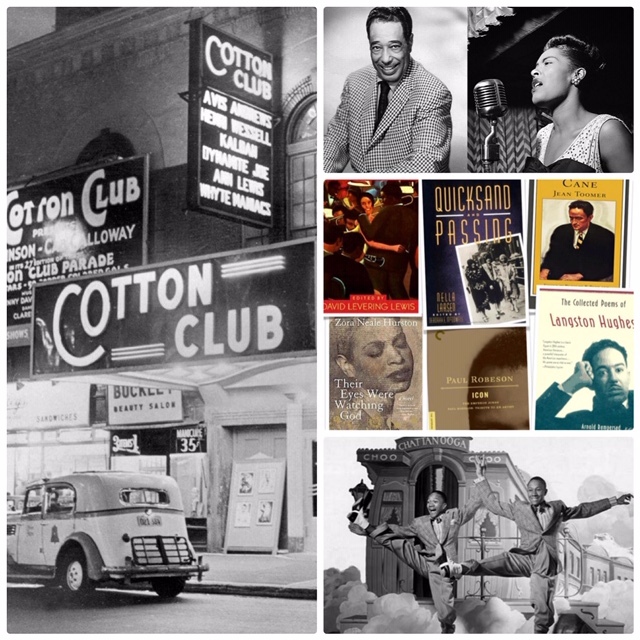

Zora Neal Hurston and Langston Hughes were strategic leaders of the Harlem Renaissance. Much has been written about them and the work of that movement’s luminaries has been widely studied and published.

The Harlem Renaissance was, of course, a confluence of Black intellectual, creative, literary, political, and musical creativity. It began with Black geniuses living and working in Harlem in New York City during the 1920s. They were even lovingly referred to as the “Niggerati” by Harlem Renaissance charter member Wallace Thurman.

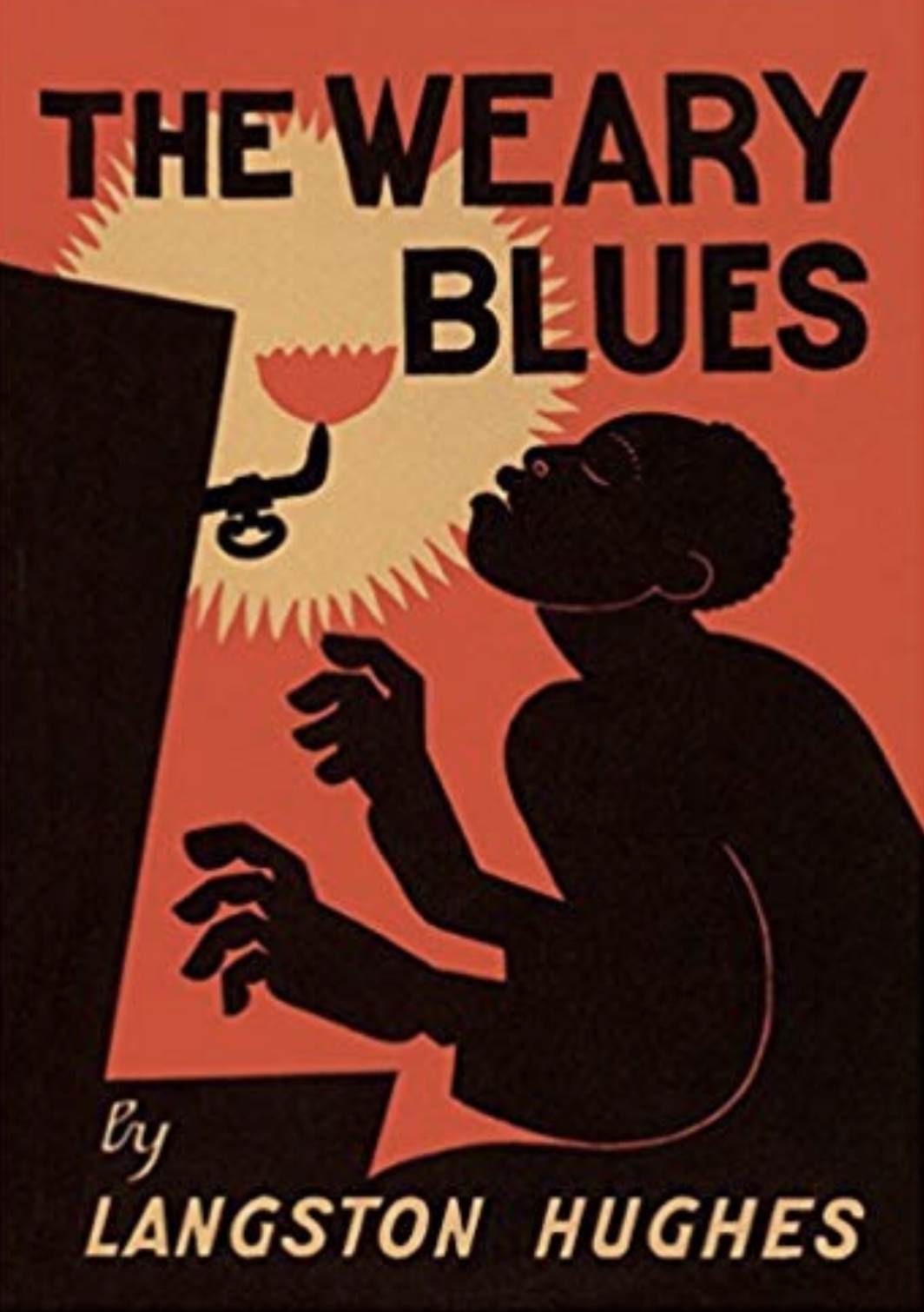

Many Harlem Renaissance members were Afro-centric in their approach. Consider Langston Hughes’ 1925 poem, The Weary Blues. In the book, Taylor quotes Hughes:

“The blues was one of the few unchallenged modes of African-American expression. Spirituals were, in part, derived from Methodist hymns; ragtime owed a great deal to European pianism; jazz came to some extent out of the military band. But the blues owed nothing to white culture.”

August Wilson picked up the Langston Hughes theme in his 1996 documentary The Ground on Which I Stand. He takes issue with the term “of color” when referring to African Americans, as do I.

Wilson says, “We are not ashamed and we do not need you to be ashamed for us. Nor do we need the recognition of our Blackness to be couched in the abstract phrases like ‘artists of color.” Who are you talking about? An Eskimo? A Filipino? A Mexican? A Cambodian? A Nigerian? Are we to suppose that one white person balances out the rest of humanity lumped together as a nondescript ‘people of color?’ We are unique and we are special.”

The Feud

As to the “betrayal” referred to in the title of Taylor’s book: Henry Louis Gates stated that the fissure that took place in January/February 1931 between Hurston and Hughes “was the most notorious literary quarrel in African-American cultural history.”

Zora and Langston had agreed to collaborate on a theatrical play – Mule and Man – with both attempting to shield the effort from the “pre-approval control” demanded by their funding patron Charlotte Osgood Mason.

In October 1930, Zora copyrighted the play under the title De Turkey and De Law in her name alone. After copyrighting it, Zora continued to work on the play, excising as best she could whatever she considered Langston’s contributions.

Hughes heard about this and asked of a colleague, “Is there something about the very word ‘theatre’ that turns people into thieves?”

On January 19, 1931, without consulting Zora, Langston used his version of the play, which he called The Mule-Bone: A Comedy Of Negro Life. He gave Zora credit for her contributions and listed her name on the title page. And he got the play copyrighted despite the fact that the entire play had been copyrighted previously by Zora alone.

The quarrel ended up involving literary agents, lawyers, theatre impresarios, and many attempts at reconciliation. No matter which side you agree with in the custody battle over their theatrical offspring, Hurston appears to have had some character flaws.

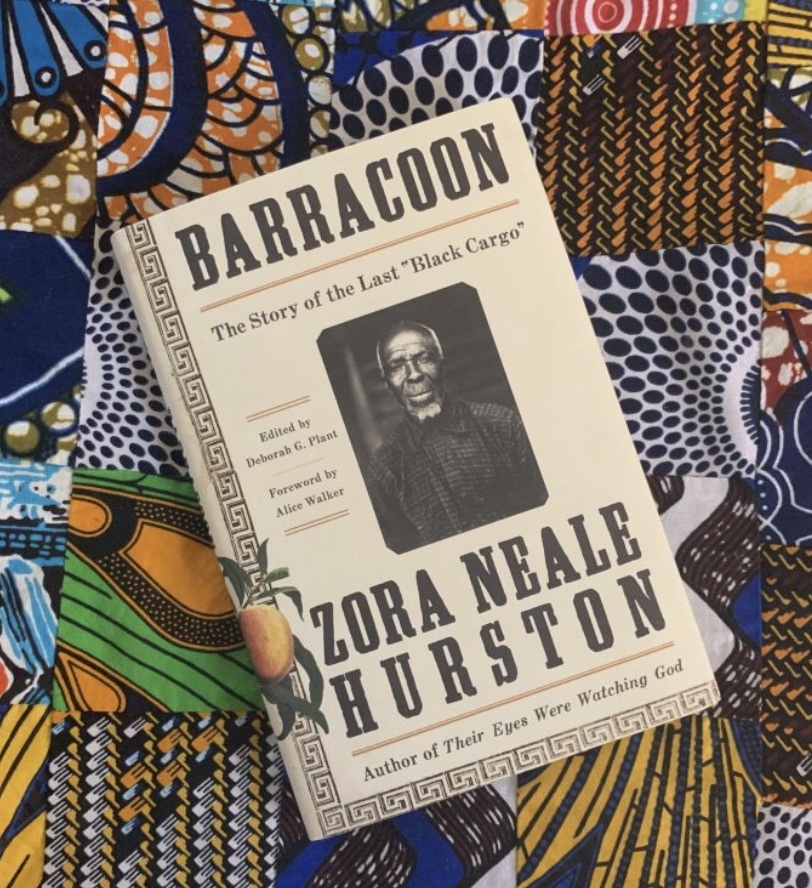

Casey Cey, in his New Yorker review of Baracoon, written by Zora Neale Hurston, points out that she made another slip. Cudjo, the former slave and the book’s main subject, was said to be the last living survivor. Hurston found out that there was a former slave woman, Allie Beren, still alive and ignored this, continuing to refer to the Cudjo as the last and only.

After other acts of self-sabotage, Hurston died in 1960. Alice Walker went looking for Zora’s unmarked grave and when she found it in 1973, she paid for a gravestone. And, to our great benefit, Walker resurrected Hurston’s work for posterity, publishing in MS magazine her article, In Search of Zora Neale Hurston.

Here are a few other take-aways provided by author Yuval Taylor in the book:

• Wealthy white patron-of-the-arts Charlotte Osgood Mason, who insisted that she be referred to as “The Godmother,” subsidized Hurston, Hughes and several other Black artists, spreading around some $75,000 – or about $750,000 in today’s coin.

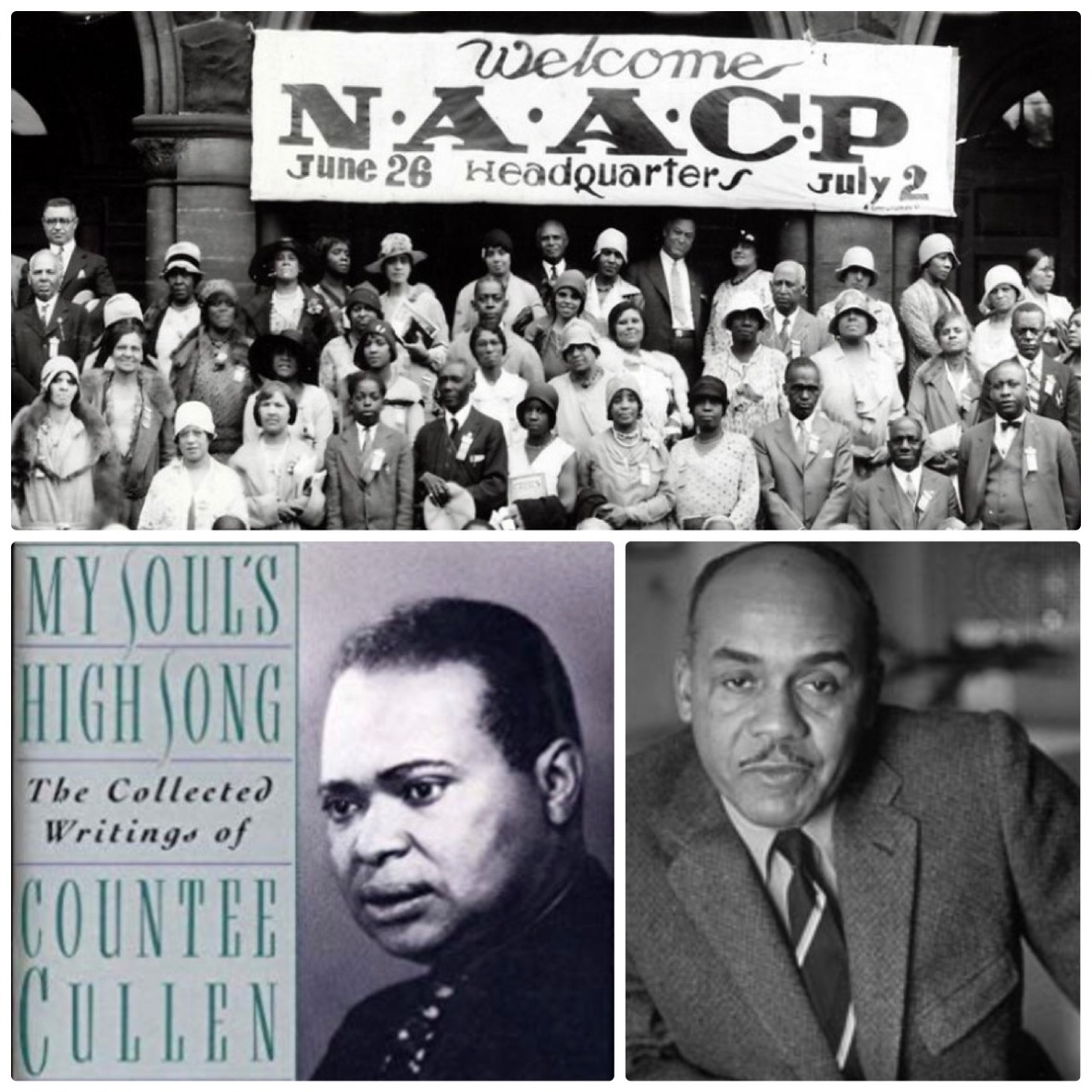

• Harlem Renaissance members included such geniuses as James Weldon Johnson, Dr. WEB Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Alaine Locke, Jean Toomer, Claude McKay, Jessie Faucet, Countee Cullen, Zora Neale Hurston, and Aaron Douglas.

• They helped one another. For example, Alaine Locke introduced Hughes to Charlotte Osgood Mason; Hughes in turn introduced Hurston to Mason – Hughes and Hurston ended up receiving stipends of $200 a month, equivalent to about $2,000 today.

Harlem Renaissance Legacy

The Harlem Renaissance laid the groundwork for many things, including most collegiate African-American Studies programs.

In addition to the art and stylish protest, the Harlem Renaissance movement set in motion enduring processes that continue to benefit Blacks – and the larger society – to this day.

For instance, WEB Du Bois founded the NAACP, the Black organizational powerbase that most recently assisted Democrat Doug Jones in his struggle to become the U.S. Senator from Alabama.

Countee Cullen was the middle school teacher of author James Baldwin, who in turn cast an outsized imprint on current Black thought leader Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Langston Hughes wrote for the Chicago Defender for 20 years, influencing Black housing and employment issues. He also introduced Ralph Ellison, the author of the classic Invisible Man, to Richard Wright, who gave Ellison his first published book review opportunity.

Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright August Wilson was once being steered into becoming a lawyer. But reading Langston Hughes and Ralph Ellison set his mind on fire – or so he told me not too long ago over dinner – and led him to becoming a writer. One can hear Hughes’ rhythms in Wilson’s play Joe Turner’s Come and Gone.

Consider Pulitzer Prize recipient Jackie S. Drury’s achievement in Fairview, a comedy turned confrontation that challenges the white gaze through which Black art is often filtered. The play exudes the art of August Wilson with its mystic power. So, make it Hughes to Wilson to Drury – tic, tac, toe.

Then there’s The Fire This Time. Michael Paulson and Nicolle Herrington further illustrate in the New York Times the connecting link between the Harlem Renaissance and today’s Black playwrights.

Now comes the immense value, practical utility and just plain delight of Yuval Taylor’s new book Zora and Langston. More than ever, I think, it’s critical for Black people to get woke to the importance of these cultural icons.

To that end, here are some other sources of inspiration:

• The Vivian Harsh Society Research Collection, located in the Carter Woodson Library at 95th and South Halsted Streets, has Langston Hughes papers available for study.

• August Wilson’s play Joe Turner’s Come and Gone remains inspirational, with its echoes of Ralph Ellison and Langston Hughes.

The Smithsonian Folkways Recordings CD Every Tone A Testimony includes Claude McCay’s recitation of “If We Must Die” and “The Negro Speaks Of Rivers” recited by Langston Hughes. I guarantee you won’t feel the same after hearing those.

• The DuSable Museum has an unforgettable Harlem Renaissance collection.

• In print or online, one can read the plays of August Wilson and connect the dots to Langston Hughes’ poetry.

But first, check out Yuval Taylor’s Zora and Langston. Hold on tight, because it’s strong enough to pull y’all safe from the Trump vortex!

(N’DIGO contributor Paul King is a construction industry consultant and member of the Business Leadership Council.)