This is graduation time and I want to tell you about my friend Michelle “Mikki” Agins, who is being honored with a Doctorate of Communications degree from Dominican University (formerly Rosary College) in River Forest, Illinois.

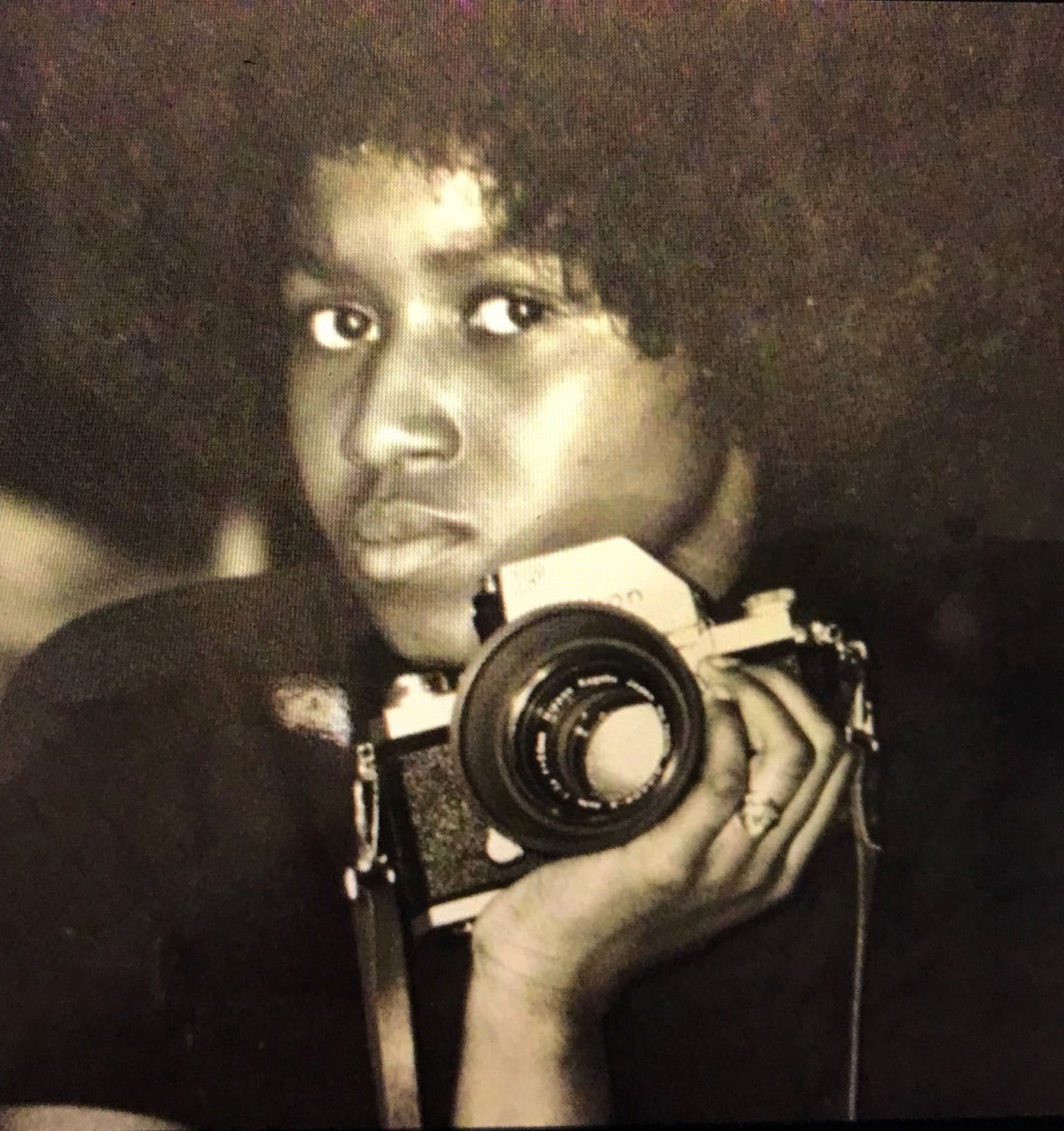

Mikki’s story is one of challenges and how she followed the path to success. When she was eight years old, her grandmother gave her a camera, with no instruction or classes.

Mikki grew up on the South Side of Chicago and discovered that when she was out taking pictures, her status soared. She took pictures of the neighborhood wine connoisseur as he drank his wine leaning against the wall in the alley. She has another of the dope dealers in the neighborhood that is still among her favorites – she titled it “The Transaction.”

People wanted Mikki to take their picture. She was Ms. Candid Camera, traveling the neighborhood learning her craft.

I met Mikki in a most unusual circumstance. My ex-husband, David Wallace, was the Communications Director for the City of Chicago’s Department of Human Services (DHS). He worked with the late Cecil Partee and his buddy Ben Branch. They were quite active and enjoyed their work and were constantly doing boundless things as they traveled the city.

One day after he left work, David had to return to the office for something he forgot. There was Mikki. Mikki was working at DHS waiting to be hired. At that point, she was the unofficial official photographer. She worked with no pay.

When David went back to the office, he saw Mikki camping out in the photo lab; she had a sleeping bag on the floor. Upon being discovered, Mikki confessed that she was living in the darkroom.

She would leave the office at closing time with everyone else and return later to sleep on the floor. She explained to David that she couldn’t go back to her neighborhood and staying at work was just fine. She was downtown in Chicago. She felt safe.

David suggested that she come home with him to meet his wife. He called me to say set another plate for dinner, we are having a guest. Mikki came to dinner and was somewhat unkempt. She was invited to stay with us for the night in the guest bedroom.

Well, that overnight became a couple of years. Mikki was eventually hired at the Department of Human Services. She was quite the photographer, as well as a great cook with a big and pleasant personality. She became a part of our family in every way. She was my little sister.

The Constant Shooter

Mikki was shooting constantly. She ate, breathed and slept photography. She had her camera bags as she shot on sites with John White, John Tweedle and Bob Black after work. They were her mentors and, indeed, she was a work in progress. They were all established professional photographers and worked at the Chicago Sun-Times.

Tweedle was one of the first African-American photographers to work for a major newspapers. He became Dr. Martin Luther King’s photographer when King moved to Chicago for a period. He worked at the city as the official photographer for Mayor Michael Bilandic and he had a studio on 53rd Street.

They were the best photographers in the city. Mikki was happy to travel with them at any hour of the day or night. She wanted to be a photojournalist and was preparing her portfolio constantly. I remember she came home one day crying her eyes out. She had shown her portfolio to her mentor, John Tweedle. He took a look and tore her photos up. She was so hurt. He said they were not her best, go do it again. She did.

She wanted so to work at the Chicago Sun-Times; that was her dream job. There were no women photographers at the Sun-Times, however. But Mikki kept trying, she kept presenting her portfolio for hire.

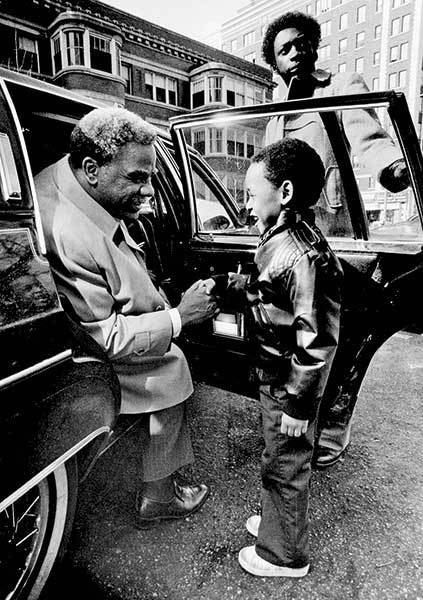

When Harold Washington ran for Mayor of Chicago, she followed him everywhere, shooting the campaign. She worked with no pay, as did the Chicago Defender’s photographer Antonio Dickey. They went everywhere with Harold. After Harold won, they both became City Hall photographers. Mikki broke the mold – she was the first woman hired and was following the footsteps of John Tweedle, who died with his cameras on at City Hall as Michael Bilandic’s photographer.

The Chicago Sun-Times never hired Mikki and whenever they denied her, it was traumatic for her. After the tears and a glass of wine, I said to her, Mikki it’s probably time for you to leave town and look elsewhere. Damn the Sun-Times.

She followed my advice and went to work for the Charlotte Observer in North Carolina. They hired her to be a sports photographer. That was perfect for her. She loves sports. She told Harold Washington about her new job, but he was discouraging, telling her that she had a great job at City Hall and he didn’t want her to leave.

He told she was secure with a great job and suggested she take a leave of absence. Not one to mince words, Mikki told the Harold that he, too, had had a great job in Congress, but he took his shot to run for mayor anyway.

She told him of her dream to be a photojournalist and Harold smiled and said he would write the publisher and editor a letter of recommendation on her behalf. He did; he wrote a glowing letter for her. Mikki moved to Carolina, knowing nobody and happy to be a part of a newspaper staff, finally. Harold died three weeks later.

Off To New York

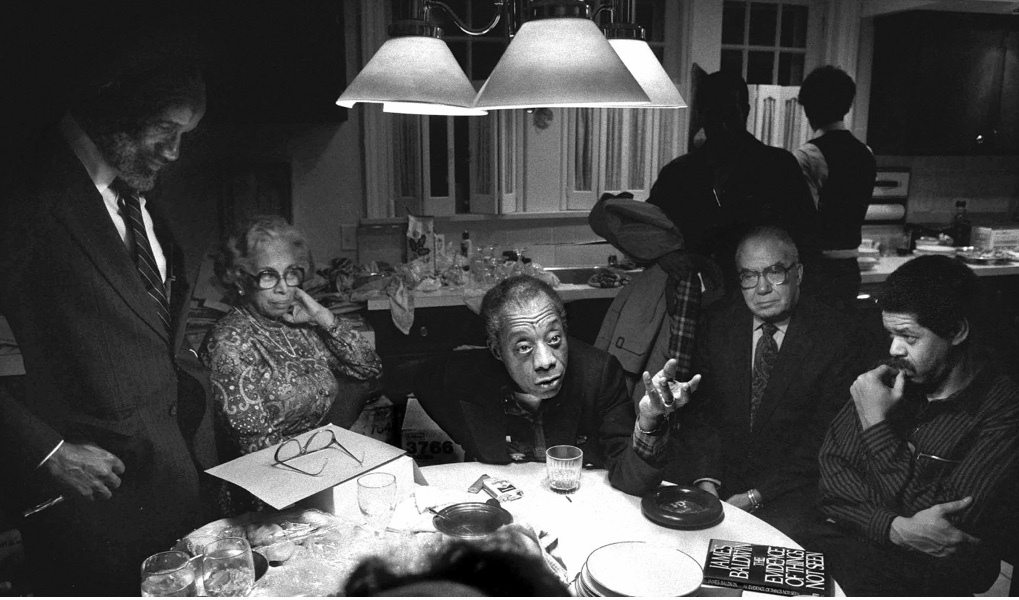

Mikki attended a Black journalists meeting where she learned that the New York Times wanted to hire an African-American photographer. She applied. Her portfolio had expanded from fires; police calls, urban scenes, mayoral photos and sports were all a part of her portfolio by then.

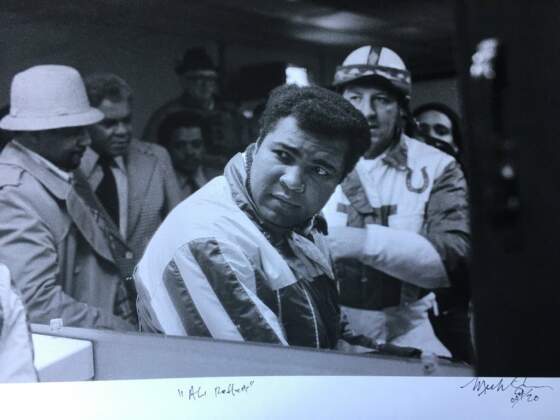

Along the way, she had met Muhammad Ali and he loved her work. She photographed Ali running, playing with the kids, walking and driving. They adored each other and had fun all the time with silly pranks.

Mikki was hired by the New York Times in 1989 as the second African-American woman to be a full time staff photographer. She moved to New York in 1989, the year I started N’DIGO.

She was happy. I kept telling her to trust God and keep on shooting. She was being directed. She was on the national stage, but once again in a strange city, where she knew nobody. She called often as she was adjusting, telling me about the big busy city. I was telling her about starting a newspaper.

Mikki had her challenges in New York, but she was ready. Her first assignment was a race riot. She was threatened, but she was tough; she was from Chicago. She covered a high society affair at Tiffany’s and the police were called by someone saying she was impersonating a photographer. All because she was Black.

But the New York Times backed her forcibly. She began to cover sports and the New York Knicks basketball team became her favorite team. She was one of the first photographers at 911. She called me that morning to say something terrible had happened as she was on her way to work. She saw the airplanes crash into the World Trade Center.

She told me she was covering it, but might not get out alive. She told me where her valuables were. She was among the very first photographers on the scene. She was shooting.

She called back in a couple of hours to say she had white stuff all over her. She had been told to go home and shower to get the substance off. She did and then went right back to the scene on her bike. She called on the hour to update me.

It was a frantic day. I cried all day long. She kept shooting, she was telling me what she was shooting, just in case. I was keeping a log. After I saw it on the news, I was frantic for her. She was crazy, but shooting all the way. She eventually fell out and slept for a couple of days after she kept washing off the “white stuff.”

Mikki followed her dream with a lot of support. She makes friends easily. She is a world-class photojournalist. She is award winning. She has received two Pulitzer Prize nominations and in 2001, Mikki and her New York Times colleagues won the Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting for their series “How Race Is Lived In America”.

This year she won the Joseph A. Sprague Memorial Award in New York. It is the highest honor bestowed by the National Press Photographers Association, and Mikki is the first Black woman to receive it, as she joins fellow honorees Gordon Parks and John White.

Some of her Chicago friends and I were there in March as Mikki accepted the award, as were her New York friends. She received a standing ovation. I cried tears of joy. I saw her dream come true. I called David and said, I wonder what would have happened had you not brought her home, We nurtured Mikki in many ways and I now realize we made a difference in her life. She was an accident that came our way.

The New York Times sent her back here to Chicago to cover the recent mayoral campaign. She was at the victory party for Lori Lightfoot and caught the action of history in the making. She will return to cover the inaugural on May 20.

I told Mikki you have made your very own history and now it’s time to think about books and exhibits. At this point you have captured a very significant history. She has photos of Trump, Bloomberg, Serena, the cabaret scene, openings of Broadway plays, the games. She still mostly favors her Chicago photos, now and then. She showcases them whenever she can.

This week, Ms. Agins returns home to receive a Doctorate of Communications for her work from the college where she experienced racism. I am so proud; I am the beaming big sister. I am proud of her work, but most of all, I am proud of the woman she became as she kept living and following her dream, no matter the obstacle.

David is proud, too, that he discovered her in the darkroom.