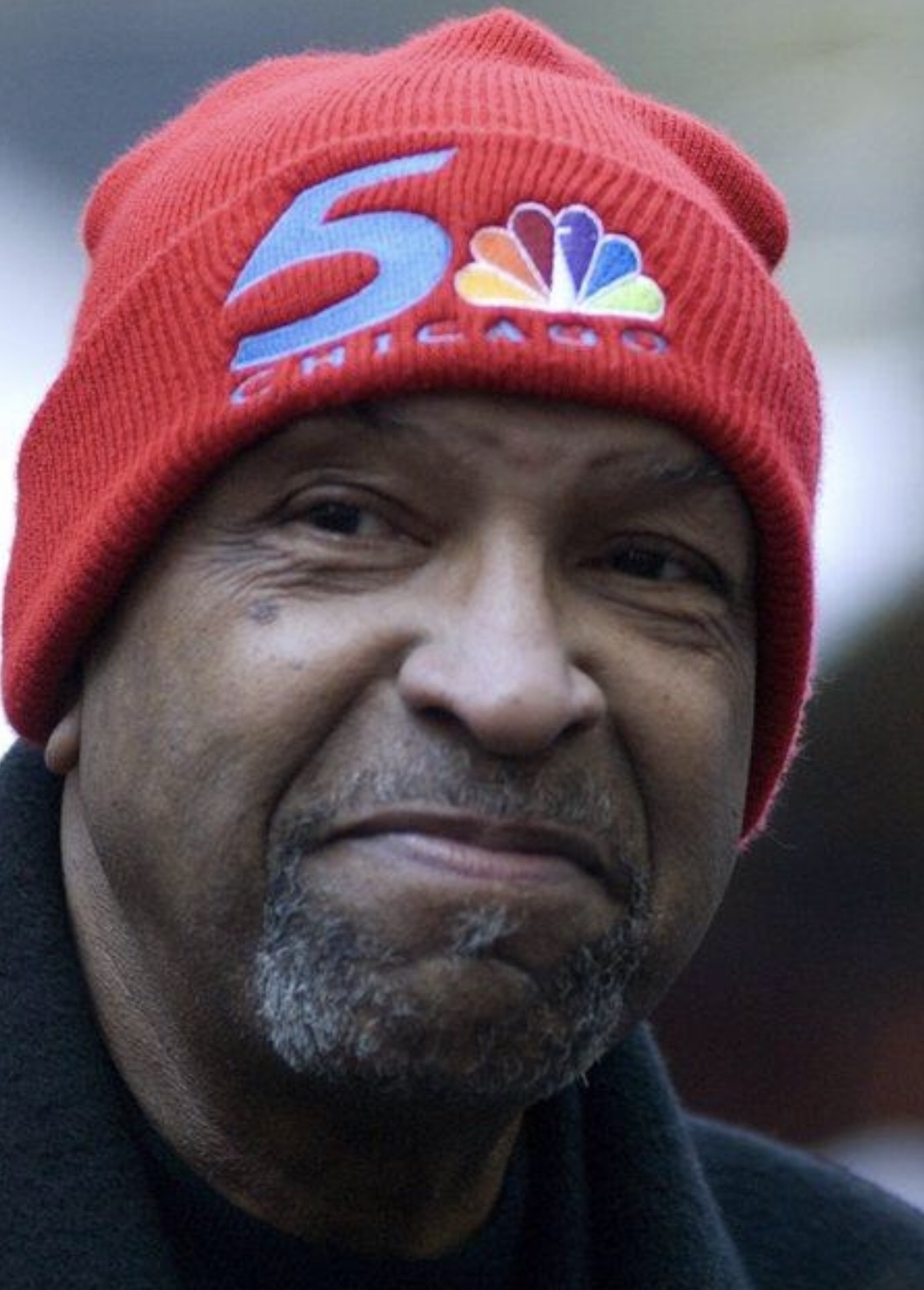

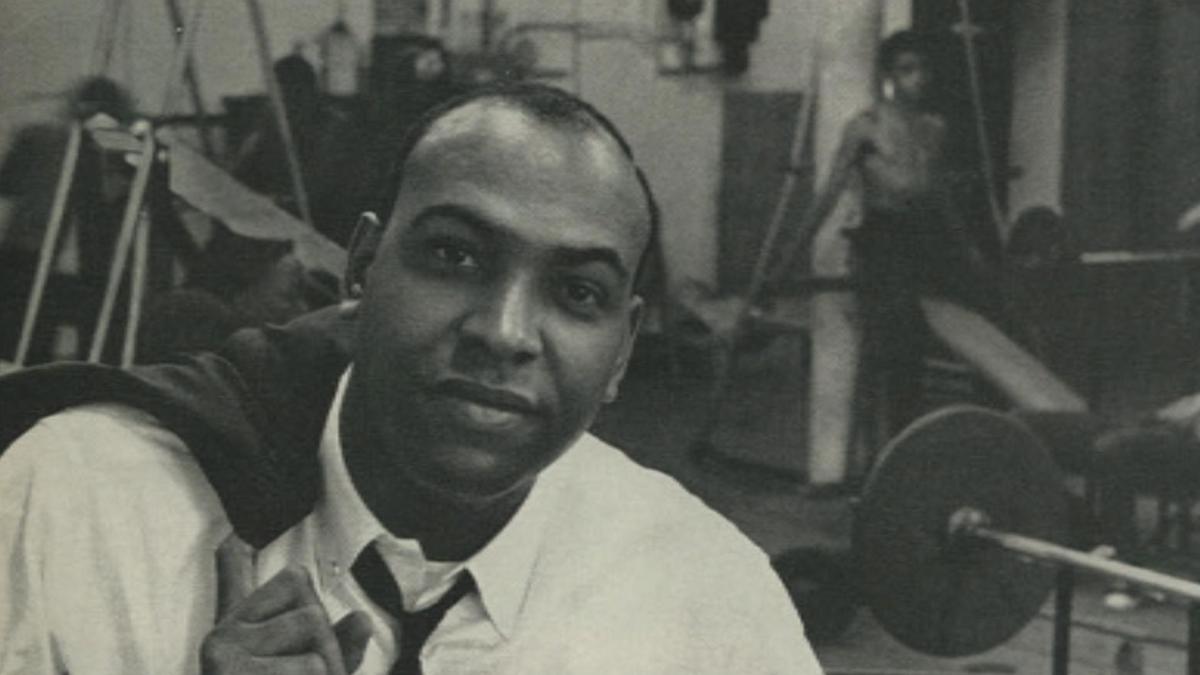

Warner Saunders was a prince of a guy. A tough guy, yet a nice guy. A guy on point and on purpose. A straight-ahead guy. A guy who told it like it was whether you wanted to hear it or not.

The longtime pioneer Chicago newsman was a Black man who told the Black story and was inclusive in his approach before it was popular and everybody loved him. Warner was hip and always on. Warner was an untrained, unorthodox journalist representing the community who became one of the best broadcasters in the business.

He recognized racism and attacked it when it arose. He called it “from the streets to the suites,” meaning he knew how to listen to the drumbeats of the streets as well as the business-speak of corporate boardrooms. He knew the people from the gangbanger to the mayor to the CEO. And he did, he really did. His resources were vast, his network broad.

(January 30, 1935 – October 9, 2018)

Warner was a good Catholic; he would proudly tell you that he went to school at Corpus Christi and played basketball and graduated from Xavier University in Louisiana. He held a master’s degree from Northeastern Illinois University. He taught school and he and his students once threw textbooks out of the window because there was not a line or picture in the book about Black people.

Warner was a fixture at the Better Boys Foundation on the West Side, where he was the Executive Director and developed programs to get the boys off the streets. He worked with the gang members and transformed many of them.

Warner was the kingpin of the West Side for all that mattered. In 1968, after Dr. Martin Luther King’s murder when the West Side went up in flames, Warner walked the streets to bring calm. He walked the streets alone, but worked with everybody successfully, from politicians and policemen to the angry rioters.

At that time, the TV news channels finally recognized they did not have Black reporters or programs addressing the Black community. An opportunity arose.

ABC-TV, Channel 7 in Chicago, started a public affairs program called For Blacks Only, which was hosted by the late newspaper columnist Vernon Jarrett and the popular radio disc jockey Holmes “Daddy-O” Daylie. The broadcast dealt with Black subject matter exclusively.

But Daddy-O soon realized that he did not like TV so he stayed with radio and was succeeded as co-host by Warner Saunders. A new career began. Warner was wonderful and the show was part-time, but weekly. He seized the TV opportunity.

Common Ground

After a while, CBS-TV, Channel 2 in Chicago, came a-calling with a new show called Common Ground and a new department for the station called Community Affairs. This was a benchmark and where and when I met Warner up close and personal. We were the hires of a new guy in town who wanted to rock Chicago’s TV world. Neil Derrough had new ideas and he wanted new people on his team. He eventually went to CNN and ran Ted Turner’s new venture.

Warner and I both were in pioneer territory. I was his producer at Common Ground and that was my entrée into media. I was also his assistant in the new Community Affairs department. We were both thrilled for a great opportunity.

Common Ground was the longest running program of its kind on Chicago TV, originally airing in a 90-minute time slot. It was the original spot for The Irv Kupcinet Show, but Kup had left CBS and gone to WTTW.

We were determined NOT to do a public affairs program, but a newsworthy one instead. We were not going to be “Negroes” on TV. We were determined to bring about a change, and we did as we participated at the executive level and with our very own show.

I was creative and had at least a million ideas a day. The first thing we did was determine our mindset. Warner said to me, we have to produce a great show so that we can win an “Emmy” because that’s the only way we will stay here. I agreed.

We were off and running and sure enough we produced award-winning shows with uniqueness and firebrand programming. We were hot and must-see TV late on Saturday nights. In the span of his career, Warner won 20 Emmys.

CBS was in its golden years. Walter Jacobson and Bill Kurtis anchored the news and they were the best in town. I got to work with them and fed them information and met with Lee Phillips and Bruce DuMont on occasion for the noon show. I visited their offices often looking for authors and talking ideas and Lee was always good for fashion tips. They, too, were about doing news shows rather than mundane public affairs. We all had the same idea. The station was hot and number one.

Warner and I argued much, too much. I wanted this, he wanted that. I thought we should have this one, he wanted that one. We were looking for controversy, innovation, and newness, cutting-edge stuff. We wanted controversy that appealed to all and engaged our audience.

Warner was a tremendous interviewer and always had his eye on the news department. In the beginning, I was staying up nights writing questions for the guests and if he didn’t ask them I was furious. He might say the question wasn’t relevant or pertinent or something like the conversation took a different turn. One time I didn’t provide questions at all and he was furious.

I smartly responded you are not using them anyway, so what. We eventually found our compromise and rather than give Warner 20 questions, I’d give him 10. We began to talk about our guests and subjects together and eventually found our own common ground. We were an interesting unmatched team.

We got the groove of and for each other and sailed upward as we both were learning a new industry and starting new careers. There were a couple of times when I stayed in the studio or the editing room all night to complete a program. What I realize now that I didn’t then is that we had a healthy version of “creative tension” – which is always good for a final product, but sometimes a hell of a process.

We had real power at the station. The news department asked our opinion and even better, the executives asked for our input. We were successful in groundbreaking decisions. The station liked innovation and they were not afraid to try something new.

We hired a lady named Edwina Moore. She was very dark, with beautiful black skin, and had a very short natural. Her look became controversial. We also hired Renee Pouissant. She was lighter skin, mid-brown, also with a short natural. But Chicago wasn’t ready for Black women with short naturals on television news. They were both excellent and Renee went on to become an anchorwoman in Washington.

We were behind the scenes in support. Both women were very talented and excellent on air. They also hired Van Gordon Sauter for the news. He had a different kind of set. He wore suspenders, shirt, and tie, with no suit or sports jacket and had a parrot in the background over his shoulder. He rolled up his sleeves and talked to you about the happenings of the day, straight ahead. It was strange and very eccentric.

The station got serious feedback on all the newbies. In meetings Warner was quite verbal to say, Sauter looks like a nut with his parrot, yet you question Moore’s natural look and skin tones. Really now. Moore eventually left the market. We realized we were fighting racism in TV in a variety of ways, from guests to looks to stories.

Warner and I talked a lot about clothes and appearance since we knew we had to dress like fashion plates for work every day because you never ever knew where the day would take you. He started calling me “Loretta Young.” I called him “GQ.”

We parted ways but remained friends and he was always there for me. He was watching what I was doing and I was watching him, too. I became a full-time educator at the City Colleges of Chicago and eventually climbed the academic ladder to become Vice Chancellor. I used to call him to say this is your “producer” and he would call me to say this is your “boss.”

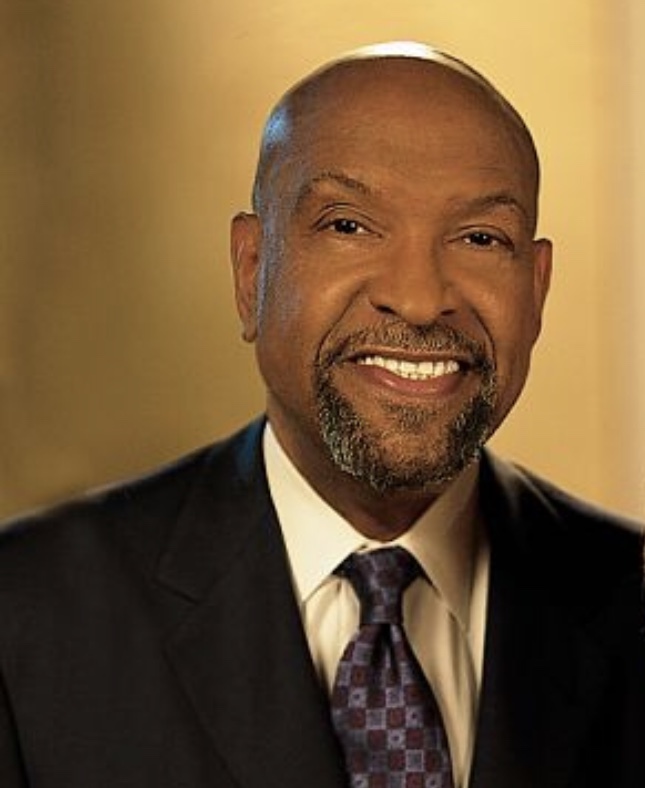

Warner eventually left CBS to become a general assignment reporter at NBC, where he remained for 29 years as a sportscaster, weekend anchor and eventually weekday anchor. He was marvelous. He could tell a story, he knew every community, and he was the friendly face in your living room. Warner loved people, he loved meeting people and hearing their story, no matter what it was.

We talked often. Once, I produced a recruitment campaign for City Colleges called “For the Love of Learning.” It included print, radio and television commercials and before placing it, I showed it to Warner in its final form for his critique.

He loved it and said you must always win the awards. I think you will win awards and get some new students too. The campaign was wildly successful, increasing student enrollment by 25 percent and we won international awards.

We laughed about our previous conversations at CBS, that we must win “awards” because we are Negroes and that’s the only way we will stay here. That was our private joke, but we both meant it and practiced it.

His N’DIGO Influence

When I started N’DIGO in 1989, Warner’s was one of the first calls I got when he saw the paper. I kept the paper under wraps and just had it pop up one day. He liked it; he invited me to lunch to discuss it. He asked tough, kick-you-in the shins question. “Do you think you can do this? Who is working with you? Where are your resources?”

I told him we were all fresh and new and our group had varying levels of experience, that we were not in the newsrooms, but wanted to share perspective, personalities and insights on Black people that was either missing period, or tell it from a different angle.

He agreed that’s what it was all about. We both agreed we were fighting racism. “I want to change the Black image,” I told him. He was very supportive and began to read our stories and make them his news.

Warner would take reporters in his newsroom on a Chicago trip where he forced them to tour the entire city. Warner and I had done that with our bosses at CBS every weekend for a month; we drove them all through the city in a limo, showcasing all of the neighborhoods. That experience helped us all when we were in meetings making decisions on what to support.

While at CBS, Warner gave me an assignment working with interns. I resisted, but he insisted. His point was that we have to teach as we go. Our interns were from Northwestern University and eventually we got into a great rhythm with them as we provided practical experiences inside the television industry.

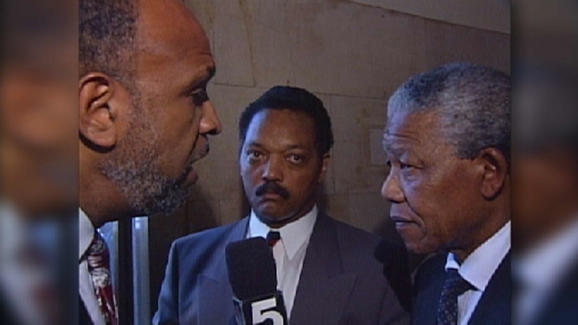

One day Warner called me and he was on fire. He had been to South Africa and was one of the first reporters on the scene to interview Nelson Mandela on the day he was released from prison after 28 years.

He had accidentally met Rev. Jesse Jackson at the airport in South Africa and tagged along with Jesse to Mandela’s living room as he came home. It was a fascinating encounter from a birds-eye view perspective.

When Warner returned to Chicago, he wanted to do a special on this historic moment for his TV station, but they would not agree to it. He told me, I want you to tell this story. This is an N’DIGO story.

I said okay. So we got to work, and along with his cameraman Chris Blackman, who accompanied Warner to South Africa, and N’DIGO Editor David Smallwood, we did what I consider to be one of the best ever stories for N’DIGO.

(That story appears in the book, N’DIGO Legacy: Black Luxe – 110 African American Icons of Contemporary History)

Warner was most pleased and hung that cover story of N’DIGO on his office wall. He agreed with me that’s really why we need the Black press. We must tell our story. Eventually NBC agreed to the special program with Warner and Mandela and it won an Emmy.

My Mentor, Advisor, and Friend

What I realized upon Warner’s unexpected death last week is that he was a tremendous mentor to me. He always called me and I had an open door policy with him. We talked about the hard stuff.

Once Warner called me for lunch and said, I need to tell you what you are really doing. Your mind set is that of a producer. Your N’DIGO cover is a TV screen with a big pretty picture and your stories are “TV news stories.” Wow, he blew me away with his observation. He was right.

He challenged me and said, you need to get back in television. He always made me think. Warner told me to watch this thing called the “internet” and he also introduced me to “hip hop music.” I told him laughingly, this isn’t Miles, but he said, it’s trending, pay attention.

When I started “producing” the N’DIGO Gala, the first one was at the Terra Museum. It happened to be in the month of February – Black History Month. It was a black-tie evening and Mr. Terra himself attended. I called Warner to tell him about this event and I wanted his involvement.

He was a great person to discuss it with because through the years he had been to a million galas. He liked the idea and served as the Master of Ceremonies for the event. But his cogent advice to me was to get the Gala out of Black History Month, or else it would forever be stereotyped.

I did. I moved the N’DIGO Gala, usually to around Father’s Day in June. The Gala grew and Warner was the emcee for many of the early ones. After each event we would debrief privately on the merits of the evening. The Gala grew to become one of Chicago’s most highly-rated and well-attended sponsored events.

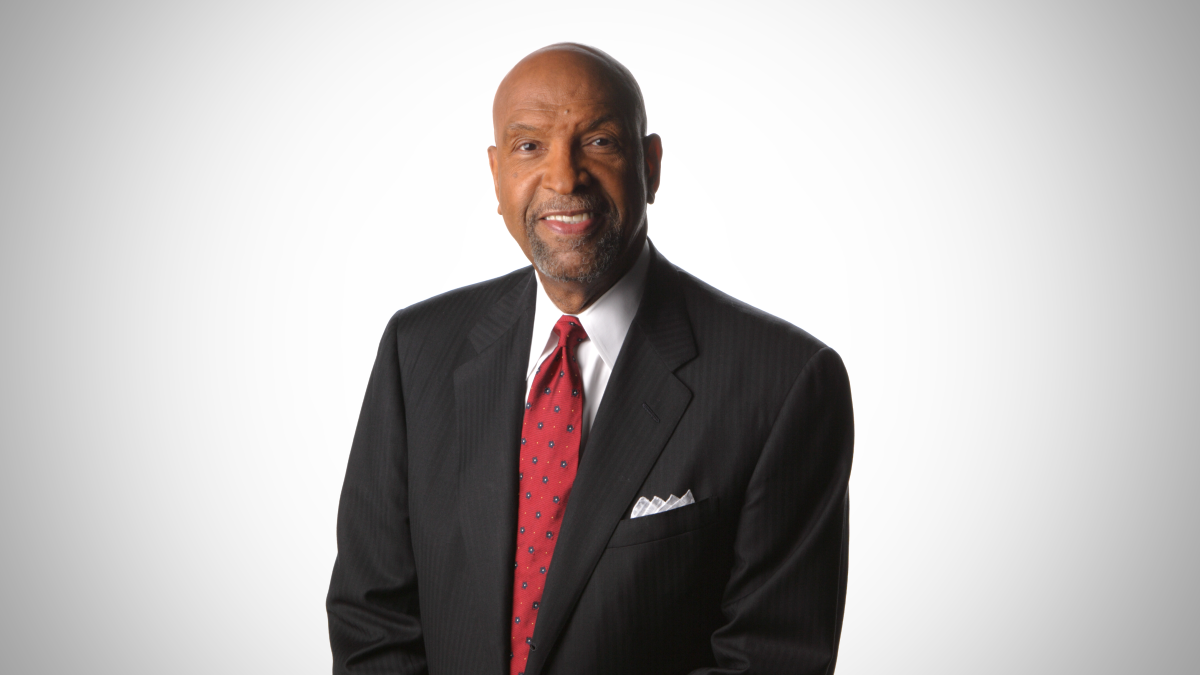

Warner said, you have to change your emcees. The next year he said, it will be Art Norman. I honored Warner with an award one year and he was so proud. Then he said it’s time for the Gala to go on TV, and we aired about three Galas on NBC.

If Warner was your friend, he was there for you for real. He argued a lot. He had a point of view. He was courageous, inspirational, a forward thinker, progressive and always hip. He somehow always knew the next step. He knew who he was and he knew the fight of racism in many ways. He kept fighting.

Warner, along with Art Norman, decided to head the Chicago Association of Black Journalists. He wanted to bring Black journalists together with a focus. He called me to join and told me to help with bringing new people in. We opened the doors to publicists and corporate affairs people. Weekly he would ask me how many recruits did I have. He built a powerful and dynamic organization.

He Knew When To Quit

Warner lived a great life, but knew when to quit. He decided to retire after nearly four decades. He wanted to spend more time with his family. He wanted to spend more time in Hawaii. The newsroom is a demanding place and for a guy like Warner, it never stopped.

He wanted to spend time with the love of his life, his wife Sadako, his son Warner Jr. and his grandson. When he was thinking about retiring we lunched and he told me his plan. I asked him repeatedly if he was sure.

I cried because I thought his presence would be missed. He said, I am retiring and you are crying. I told him there are not a lot of people like you, my friend. But he said, stop, I think I have influenced a lot of people and they are in good places.

He said, I am glad we argued so much, but I think you’ve got it. He urged me to think about television again. I agreed. He said keep on fighting, keep on doing it, keep on writing and remember to train somebody. That’s what it’s all about.

Warner Saunders was my friend and my mentor and I was about to invite him to lunch to tell him I am planning my next step in media and it’s TV. The day Art Norman called to tell me that Warner had passed, was the day I had just completed planning the shows and I was about to call him to discuss. I never made that call or had that lunch.

Thank you, Warner, for covering the news with a new perspective. Thanks for every argument that challenged me and made me better. Thanks for the innovation and encouragement.

Thanks, Warner, for a record-breaking 40 years. He indeed was Chicago’s very own.