“I saw you crying and I saw you responding, but I was just about to bust wide open. You talk about being moved, not only because Aretha is my daughter…Aretha is just a stone singer.” – Reverend C. L. Franklin

She was born into the church; she grew up there as a child and starting singing for her father’s congregation at the age of five. She never left Detroit’s New Bethel Baptist Church on Linwood. Gospel was in her DNA. The sounds of the Black Baptist church were unmistakable in her God blessed voice. That gospel sound was always there, it was her core.

She didn’t have a music degree. Her teachers and mentors were hands-on and her lessons came from the greatest ones of their day – Sally Martin, Clara Ward and Mahalia Jackson. Dinah Washington tutored her. Her dad would wake her up late at night to play and sing for Ms. Washington and Duke Ellington as they visited after hours.

Aretha had a middle-class upbringing. She was the youngest daughter of one of the country’s most dynamic preachers, nicknamed “Million Dollar Voice.” He was a colorful man who mixed and mingled with celebrities and the underground. She grew up in a household where it was common to have the most renowned entertainers of the day stop by, like Duke Ellington, Billy Eckstein, Sarah Vaughan, Ray Charles, Quincy Jones, Count Basie and countless others.

At that time, Black entertainers were not always welcomed downtown as they played the chitlin’ circuit or even the main stage. But there were certain places where you went after performing to eat and relax and maybe even lodge. That was the Franklin household in Detroit.

So Aretha was watching and listening to the illustrious ones right in her living room. She was schooled and steeped in the church, but the famous visitors exposed her to all of the music. Her dad was from Memphis, so he knew the blues. He knew the pain of being Black. Aretha got it all and soaked it up like a sponge.

Early in her life while developing a voice, a golden voice was created. She could scat, she could shout, she could hum, she could moan. Her mother died at an early age, leaving her a motherless child. Her mother was a vocalist and a pianist.

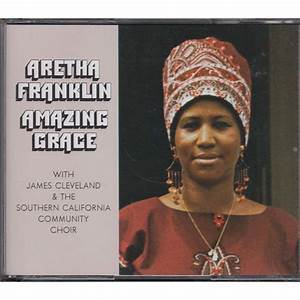

Aretha was taught by James Cleveland, the choir director at the church. He taught her the technical aspects of gospel music, the foundation of rhythm and blues. She learned to play the piano by ear. She would come back to her Dad’s church in 1972 to record with Cleveland her greatest album, Amazing Grace, the best selling gospel album ever.

In spite of her popularity and even privilege, Aretha had a difficult life. You heard it all in her music. She was a high school dropout; she had her first son by the age of 12 and a second child by 14.

Her grandmother raised her boys because Aretha was destined to sing and away she went. She had a voice that made you shout, cry and love. Her voice emoted like no other. She touched your heart and made you feel.

She knew the church world and all that came with it. She knew to wear her hat to church and to have her dress below her knees. Her voice was glorious, magnificent and phenomenal. She was special and knew it early – her daddy and his church community told her so. This is how Aretha grew up.

Black Obligation

Rev. Franklin was a friend of Dr. Martin Luther King’s. King was welcome to his Detroit pulpit and his home. Franklin was a financial supporter and a marcher. Aretha was a civil rights financial supporter, without fanfare. It was her Black duty. King and Franklin led the Freedom March in Detroit in 1963, with about 100,000 people. It was the precursor to King’s March on Washington.

Barry Gordy was also a close friend of Rev. Franklin’s and says he was stupid not to sign Aretha to his young Motown label. But Franklin managed and guided young Aretha’s career and wanted her to be with a more established record company.

She went to New York, following Sam Cooke, who had crossed over from sacred music to secular, and signed with Columbia for six years. Columbia execs knew that her voice was special, but did not know how to capture her talent.

They were trying to make her the next great jazz singer, and I love her early music; she was a mellow jazz singer. Her gospel jazzy sound with beautiful lyrics and violin backing comes through beautifully.

But she moved on to sign with Atlantic Records and her career blossomed with Jerry Wexler. He understood her better as a pop singer with original music rather than jazz classics. She was a crossover. She was on her way to becoming the Aretha we know today.

Chicago was Aretha’s second home. She traveled here with her father on his caravans and often sang with Chicago’s very own Staple Singers. Radio station WVON was here; it was the home of the “Good Guys” and blues man Pervis Spann, who was also a promoter producing stage shows.

There was a real connection between Detroit’s music and Chicago. WVON is where the music was played on the radio and the Regal Theater on 47th and South Park was the place to appear. Mr. Spann saw young Aretha’s promise and her greatness early.

It was Pervis Spann, The Blues Man, who crowned Aretha and gave her the title that would follow her forever, “Queen of Soul” at the Regal Theater in 1964.

Aretha had managers, bookers, promoters and the like, but in reality she was her own manager, her own force. She had her very own vision. Her formula was detailed in the book, Respect: The Life of Aretha Franklin by David Ritz.

She recorded and then toured to promote her music. In her lifetime, Aretha sold more than 75 million records and reportedly earned $80 million. That’s a lot of music and money. She had music in the studio at the time of her death, but was too sick to finish one last album. She also won 18 Grammys, by the way.

She was her very own woman. She changed the world of music and changed the way business was conducted for Black performers. She played the chitlin circuit, but she also transformed it.

In her day, Black entertainers often performed and were not paid at the end of the night. Promoters said things like ticket sales weren’t what they expected and the performer couldn’t get paid in full. Aretha learned on the spot. She was a great singer and a great businesswoman. She insisted on being paid in cash before the performance.

Her practice was simple – no pay, no sing. And she wanted cash; she put it in her purse and the purse sat next to the piano while she was on stage. She made all respect her. She was Ms. Aretha Franklin and Black entertainers followed her lead.

N’DIGO GALA 2012

We produced the N’DIGO Gala for 20 years. Aretha was our entertainment on June 30, 2012 at the Arie Crown Theater with the Impressions. I had tried booking Aretha about six times previously. I had been warned that she was difficult to work with and that she would cancel a performance without notice. The bookers always said think about it.

As I planned the N’DIGO Galas, I always wanted the performances to be memorable. I called them “classic performances.” I didn’t want run of the mill, I wanted special and different and, most of all, a memorable evening. Entertainment was key.

One day to my surprise, I got a call from Ms. Franklin. I am certain this call was engineered by Fred Nelson, my friend and Aretha’s longtime music conducter. She said, “How are you, Ms. Hartman? How’s the gala coming? Do you have your talent for this year?” I said, “No.”

“What about me?” she asked.” Really now. “Ms. Franklin you are too much, I don’t know if I can afford you,” I replied. Aretha said, make me an offer. I did. She accepted. And then she said, let me help you.

“I will pay for transportation and hotel and I will pay for my staff. All you have to pick up is the entertainment cost.” “Really. Ms. Franklin, you know I like classic performances, something different. I don’t want your average show.” “Okay,” she said. My people will be in touch with you.” I added, “Ms. Franklin, I have one absolute condition. You cannot cancel under any circumstance.” She agreed.

Aretha appeared on June 30, 2012, with the Impressions in a show I billed as “The Legends of Soul.” I wanted a show reminiscent of the Regal Theater, where there were multiple acts. I wanted an old-school stage show. She got it.

The night of the performance, unknown to me, Fred Nelson, Ms. Franklin’s music director, had a 100-voice choir backstage. Rev. Charles Jenkins had just released a top gospel recording. “What is this?” I asked Ms. Franklin. “This is not a gospel show, what are you doing?”

She replied, “Ms. Hartman, you want a ‘classic performance?’ Then always take gospel, you can’t go wrong. I will give you a great show and I will do everything.” Then she asked, “Do you have the cash?” I said, “Ms. Franklin, I have tried giving you this money all week.” But she said, “I get paid, right before I go on stage. I told you that,” she said.

Ms. Franklin drove to Chicago about a week before her N’DIGO Gala performance. The Drake Hotel was her choice of lodging. We talked daily around mid-day to see how things were going. I wanted to go chat with her in person at the hotel. I wanted to take her to lunch or dinner. I scheduled media appearances for her, as everybody wanted to interview her.

She said, “Ms. Hartman, I am going to give you one print, one radio, and one television.” I wanted the town buzzing with Aretha. She would not go to the studio. Windy City Live wanted to do a 30-minute show with her, exclusively. They were willing to set up the studio in the hotel room. She said absolutely not – tell them to call me and use photos and videos. Then she said, “Ms. Hartman, I know PR, you know.”

I tried to get her to the spa. I asked her did she want Lem’s barbecue. She said, “I got some already.” She wanted to know about ticket sales. She asked me had I invited key ministers. She loved Rev. Parsons and Rev. Jackson and wanted to make sure they were in the audience. “Ms. Franklin, Rev. Jackson makes every gala. He’s on my list, too,” I told her. She was always a step ahead. The hotel made a mistake one time and tried to blame it on me. Aretha called me on it, but once she realized that it was on the hotel, she said, “Ms. Hartman, I owe you an apology. I made a mistake.”

The night of the performance, she walked into the venue alone, with a Louis Vuitton bag (her money bag) and a dress wardrobe. I asked her why was she alone carrying her bag. I took her to the dressing room. We had tea and fruit and I hung up her clothes and asked if I could help her with hair and makeup. She politely said no.

“Do you have my money?” she asked. “Yes,” I said. We moved to a private room and she counted money like I have never seen; she must have been a cashier once upon a time. She was ever so cool, but I thought melancholy.

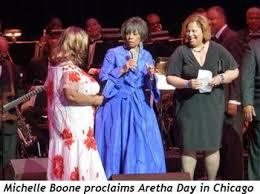

“Ms. Franklin, I have a couple of surprises for you this evening,” I said. She just said, “Okay.” We had a proclamation from the mayor naming it Aretha Franklin Day in Chicago. Michelle Boone, then the cultural affairs czar for the city, presented it.

The Impressions took the stage first and they were great. Then Aretha walked on stage, introduced by Art Norman. She took her Louis Vuitton bag with her money in it and sat it at the piano. Then she sang, and sang, and sang. She sang with the choir. She played the piano. She sang the pop tunes. She sang a little jazz at my request.

When the show was over, she came backstage, with her band and musicians and singers following her. They locked up. She paid them. She penalized a couple of the singers – she said they had missed a couple of notes or entry points and she cut their pay.

I tried to take up for them by telling Aretha, “Don’t do that, they were great.” Aretha then gave me a nice long stare that said, ‘Stay out of my business.’ She was a perfectionist and the stage was her world. She had an ear. She heard every note and noticed every miscue.

After the band and her crew left, the press wanted to come back to meet and greet her. She told me, “You’ve got 30 minutes for photos and VIPs.” Candace Jordan and her husband, along with Jesse Jackson, entered Aretha’s dressing room.

Candace, the ultimate sophisticated lady, became a screaming teenager and fell to her knees to greet Ms. Franklin. She was gracious and laughing. Ms. Franklin said, “Who is that pretty lady?” “Candace is a high society writer for the Chicago Tribune and a teenager who loves you,” I told her.

The after-party had begun on the patio looking over Lake Michigan. We were dancing to the music of Aretha Franklin and the Impressions. The champagne was flowing. I wanted her to go to the after party and I had planned to have her arrive in a pink Cadillac. But she said no.

She thanked me for a good experience, we hugged, and then she said, “Keep up the good work with N’DIGO; I read you. Be good, Ms. Hartman.” “Thank you, Ms. Franklin.” She never broke that proper church-like protocol – she never said “Hermene” and I never said “Aretha” to her face.

Darling Of The World

In subsequent years following that gala, she would call to say hello or to tell me she enjoyed a story. Once she had Clarence Waldron call me with a scoop. Clarence was the entertainer writer for Jet Magazine and has probably covered her more than anyone. She liked Clarence and through the years gave him exclusive interviews. She wanted Jet to have her news first. Clarence eventually became Ms. Franklin’s longtime publicist.

The scoop Aretha had Clarence give me was that she was canceling her date at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas. I called Vegas to verify cancellation of a sold-out house. I didn’t think it was my story to run, I said to Clarence. She called me and said, “Ms. Hartman, I gave you an Aretha scoop. Did you really turn it down?” “It’s not mine to run,” I replied. “It is if I say so,” she said.

I added, “Ms. Franklin, I don’t think you should cancel a sold-out house in Vegas.” She said, “Ms. Hartman, sometimes do you feel like not going to work?” Well maybe. “Ms. Hartman, this is the day of the Internet. Run the story. You have an exclusive, go with it.”

Her last appearance in Chicago was at Ravinia. Clarence wrote a review for N’DIGO. She played to a packed, overflowing crowd. The story ran and Aretha called to say she enjoyed the review.

She was very much her own woman, without description. She was a Black woman, unapologetically. She was the darling of the Black community everywhere. That adornment eventually transferred to the world.

But she never left us. She took the church everywhere – to the President, to the Pope, to a Command Performance for the Queen. She was the soundtrack of the Black experience in America in her era. To mark her 25th year in show business, the then-governor declared her voice “a natural resource.” Indeed, she was a national treasurer.

We will enjoy her singing for years to come, but she was also one of the best piano players. We all probably have an Aretha story, and Aretha moment, and if you ever saw her perform, it is probably forever etched in your mind.

Some performers drop the mic; Aretha dropped the mink that she often wore on stage. She proved she was the master of every music genre and her genius was set forth when she stood in for Luciano Pavarotti in a pinch and sang the classical music piece Nessun Dorma, which she learned in a short 20 minutes. Her performance earned rave reviews.

She was an original, a one of a kind. Barry Gordy said it best: “Some people come into the world as an original for a decade, maybe a century. Aretha was one for all times.”

She lived her life. She was her own boss. She didn’t like to fly, so she didn’t. She did it her way. She had four boys and two husbands, Ted White and actor Glynn Turman. I wonder if she was ever really romantically happy.

And she even got to pick who would depict her in the upcoming movie about her life. She chose Jennifer Hudson to portray her. Her voice will live forever. She will be studied for years to come.

On Saturday, August 18, the people declared it Aretha’s day. Radio stations, beauty shops, barbershops and grocery stores throughout the city were playing Aretha. People were dancing. She will live forever. Viva, Aretha! She was the GOAT. She sung her song for the world to hear.

Thank you, Ms. Franklin.

My favorites from the Aretha Franklin Songbook are:

Skylark

If Ever I Would Leave You

Call Me

Wonderful

Somewhere

Mary Don’t You Weep

Talk To Me

Spirit in the Dark

Wholly, Holy

I Say A Little Prayer

You Send Me

Day Dreaming

Aretha Franklin will lie in state for public viewing on August 28 and 29 at the Charles Wright Museum of African American History, 315 East Warren Avenue, Detroit, Michigan 48201 from 9 to 9. Her funeral is a private service, to be held August 31 in Detroit at Greater Grace Temple.

I have been a reader for over 15 years. I enjoy the paper and the content. This is awesome to have it on my computer how handy.

Glad you are enjoying. Amazing we are reading on phones, isn’t it.