Stan Stallworth was born and raised in Evergreen, AL., and encouraged to succeed by his parents. His mother was a high school librarian and his father was a high school coach and principal with business interests on the side. Stallworth was salutatorian of his local high school and went on to attend Alabama A&M University on an academic scholarship. At the historically Black college, Stallworth was elected student body president and became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, later graduating with degrees in English and biology.

Upon graduating from the University of Wisconsin law school in 1990, he joined the prestigious law firm of Sidley Austin as a real estate attorney where he spent his entire legal career. He served as co-chair of the firm’s diversity committee and diversity task force as well as on the recruitment committee where he routinely recruited at HBCUs. He was also a member of the board of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund.

In 2013, Stallworth was accused, along with his nephew, of purposefully intoxicating a 19-year-old with the intent of sexually assaulting the young man. The story was covered by major news outlets and legal publications locally and nationally, and after two years of fighting the accusations, he and his co-defendant were acquitted after a three-day bench trial. Yet, there was irreversible damage, including the end of his career at Sidley Austin.

Stallworth made a pledge to begin the work of rebuilding his life with a new focus. At the center of that was preventing what was done to him from happening to others. “I am now dedicating my energies to speak out on the injustices that I have experienced firsthand,” he said at the time.

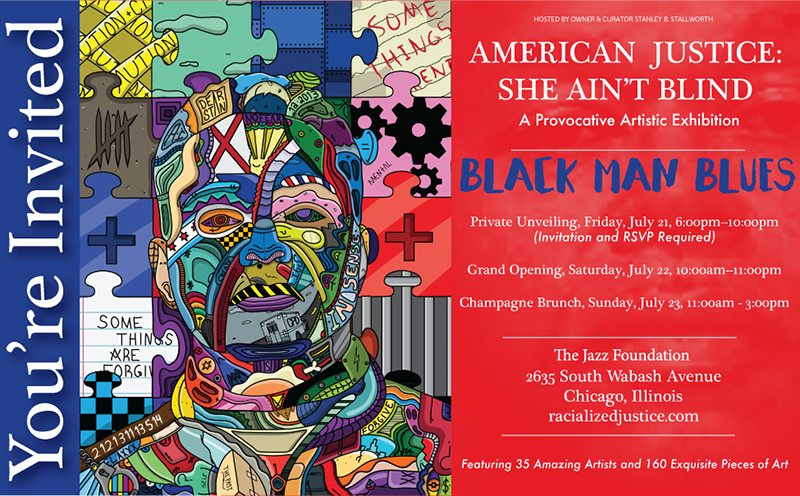

Part of Stallworth’s journey comes to fruition with the opening of “American Justice – She Ain’t Blind,” an exhibition of 35 artists—presenting in a variety of medium—all focused on the disparities of the legal system and American society, specifically as it relates to black and brown defendants. The exhibition will showcase nearly 250 works of art and opens with a VIP reception on Friday, July 21 at Steele Elliott Gallery in the South Loop.

Here Stallworth, an art collector since college, discusses his journey post-acquittal, the inspirations for the exhibit and his plans to keep shining a light on disparities within the judicial system.

What have your realized about the judicial system post your acquittal?

Although I was successful in winning my case, it was a bittersweet win for both my co-defendant and me. The prosecutor’s office had no interest in getting to the facts or presenting credible evidence to the judge.

Since my early days of being a lawyer, we were trained that cases are won on the facts. How do you fight when a case is not fact-based? What I now know is that there are hundreds of other cases that are being handled the same way and the vast majority of those defendants do not have the resources to fight that I was so privileged to have.

What did it mean for you to be on the other side of the aisle?

Innocent until proven guilty is not the criminal standard. Prosecutors go after you as if you are guilty from the beginning. They don’t want to exert the energy to gather the facts. No one came to my home; they never interviewed my neighbors or did any type of rigorous investigation. Rather, they went on word of a young man without corroborating the facts.

Why this exhibit, “American Justice – She Ain’t Blind?”

I’ve always been involved with the arts community in Chicago and began collecting when I was 18. I paint as well, and when I had time on my hands because of the case, it seemed an obvious outlet for me.

The original idea for the show came from my friend, Terisa Griffin. She called me one morning to say I should mount an exhibit and call it ‘Black Man Blues.’ I went to work almost immediately and created a piece called “Invisible,” a reference to how this situation made me feel.

After that, I began to talk to the artists who I’d collected over the years. I spoke with them in small groups of four or five, told them my story and forthrightly answered any questions they had. Some literally wept, some sent me notes after our meeting and all offered to help tell my story. You will see the name, ‘Black Man’s Blues,’ featured across all our materials.

One of the other names you use to refer to this exhibit is racialized justice. What does that denote?

‘Racialized American Justice’ refers to the concept in this country that brown people are inherently dangerous. It is that kind of irregular, excitable thinking that leads police officers to shoot black and brown people so quickly. Philando Castile (Minnesota) was just one example.

In my case, Cook County—at that time under the leadership of Anita Alvarez—did not do their due diligence. If you are a defendant, you expect and deserve a full, comprehensive and fair investigation when charges are brought against you. That is not what is happening in this city. The ‘scales of justice’ are featured prominently in many of the pieces, and in none of them are the scales equal.

Tell us about the artists and their pieces.

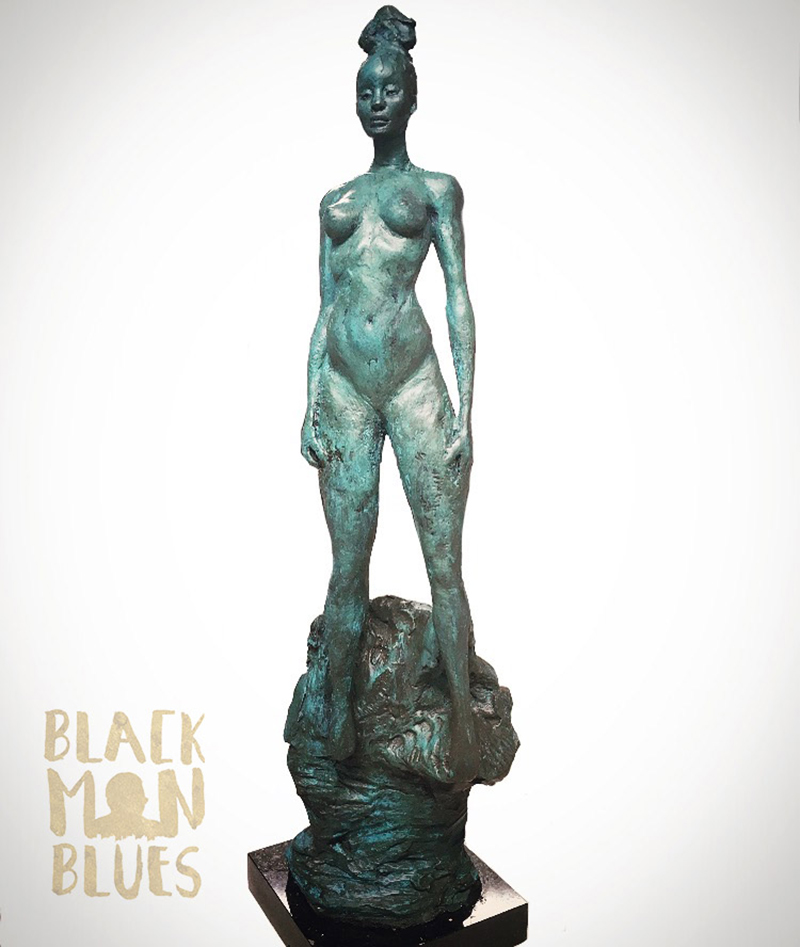

The artists represented range from those collected by the Smithsonian to international street artist[s], and those in between. I am so proud to have this kind of genius around me who can tell this story in their own medium be it canvas, metal, stone, or wood.

Originally, the show was conceived as a 30-piece show focused on social justice. But, it continued to grow to what you’ll be seeing beginning this weekend. I think the artists’ depth of emotion will come through.

One piece by artist Gerald Griffin, known for paintings and sculpture, is called “Founding Fathers,” which depicts George Washington crossing the Delaware while holding two African slaves by chains. To that piece, he added a modern-day African-American man and woman to show that the bondage has not ended.

There are other incredible artists—Martha Wade, Minnie Watkins, Dana Todd Pope, Rudolphus Thorpe of Washington, D.C. and too many to name here—you’ll certainly have to come out and see them all.

Tell us about the events associated with the exhibit.

We are at Steele Elliott Design NPF, 2635 South Wabash Ave., 3rd Flr. The venue is owned by one of our curators, artist BryantlaMont. Our other curator is Roe Melloe of Melloe Drama Entertainment. We open on Friday, July 21 with a special exhibition for collectors, media and our artists from 5–10pm. Terisa Griffin will be performing.

On Saturday, July 22, we open to the public beginning at 10 a.m. until midnight. At 7:30 on both nights, we will have a small presentation and introduction of the artists.

On Sunday, July 23, we will host a Jazz Brunch from 11am – 3pm with a special performance by Ricky Dillard New Generation. There will also be a music showcase that evening from 8 – 10 with among other artists, T-Godz, UFB Plymkrs, Lil Breeze, Isiah Hicks, $crill, and IV.

Visit our site, www.racializedjustice.com for details and tickets.

Are the pieces in this show available for purchase?

Certainly, and we are also creating a coffee-table book of the exhibition that will be available shortly.

What do you ultimately want to see come from this exhibit?

Certainly a heightened awareness of what is happening here and across the country.

One of my goals is to create programs that provide support for young people re-entering the mainstream after incarceration. We need to educate ourselves about the system, and most importantly, hold the system to the standard it is sworn to uphold.