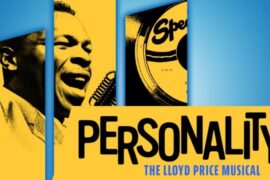

Token is a thought-provoking, one-woman comedy show by humorist-actress Kaye Winks playing its last performance this Friday, June 9 at Second City’s Judy’s Beat Lounge in Old Town, 230 West North Avenue, at 7:30 p.m. (For box office info, call 312/337-3992, or visit Second City’s web site)

In the show, through a variety of characters, Chicago area native Winks reflects on what it’s like to be one of the few or only African Americans in the room with White folks. And because she did not have the most stereotypical upbringing for a Black Chicagoan, she spends a good part of the show cracking on her misadventures with Black people, as well.

Winks’ observations on both worlds are often humorous – such as in “White people get everything, even the benefit of the doubt” – sometimes poignant, and occasionally cringe producing as this young Black woman gives her view of this peculiar thing that we call “race” – especially when both Black men and White men in her life have asked her to straighten her hair.

Winks attended Columbia College, trained at the Moscow Art Theater’s Stanislavsky School, and has been featured in commercials and print campaigns for Honda, Sony and Hot Pockets. She made her feature film debut in The Social Network, but laments that her sole line in the film was cut, though she can still be seen in background shots.

After Token’s run ends in Chicago, she’ll perform it again at the United Solo Theatre Festival in New York in September, then continue working on her script about a bi-racial kid that spends the summer on the South Side of Chicago.

N’DIGO: Would you explain your show, please?

Kaye Winks: Token is about my experiences being a token Black person in the world, in the White spaces. I take events from throughout my life and whittle them down into stories; the elements of the stories are all true in some way. It is a not dark, but very real, comedy. All my comedy is usually socially relevant and aware of itself and it may make people uncomfortable, but I think that’s what true comedy should do.

This is about ultimately, being an outsider. Every human has had an experience of being an outsider and you’re in a place and not fitting in. This show is about having that experience and the comedy that ensues when you have this experience of, “I really don’t fit in here, but I’m here, though.” And you have to sort of take it all in. I feel like everyone can relate to that.

In truth, everyone knows what it feels like to be an outsider, and that’s what being Black in our culture is.

What is the origin of the show?

When I first wrote the show, I was around them; I was in a White world. I was 24 or 25, in Los Angeles. L.A. is only eight percent Black, so we’re actually like really a minority there. You have to go out and find Black people in L.A. and I wasn’t finding them. I was surrounded and I just got tired of White people. I make a joke in the show about how they’re everywhere always. It’s really hard to escape White people.

So I just wrote what I was feeling and it was really dark. It wasn’t funny at that point. I was pretty mad. This came from a certain group of White girlfriends that I’m no longer friends with that was passive aggressive and I got tired of dealing with the micro aggression.

Talk about your background, please.

I was born in a hospital in Naperville right on the border of Bolingbrook and I spent my youngest ages there, first through sixth grade – then we moved to Indianapolis. I’m middle-class educated and suburban completely. My parents are from the South Side of Chicago. Both Black, high yellow, but they’re Black.

When I was growing up, Bolingbrook was very White. It’s now about 35 percent non-White and that’s within the last 10 years. When I was a kid, we were one of five Black families, I think, that lived there and there were no Latinos.

How did your parents get out there?

My parents met at Argonne where they worked. My dad was a physicist and my mom was an executive secretary. They both worked there for 20-30 years. That’s why they moved to the suburbs. When they first met, my dad didn’t have a car and it was hard to get there on public trans, so it was easier for him to move out there. (Naperville is about seven miles away from Argonne).

My dad also said they just got tired of living in the city. He said he wanted a better life and was tired of people messing with him. Stealing your stuff, asking you if you want some of this, or can I get this.

How long were you in LA?

For about seven years. I moved there when I was 21, so I was probably about four years in there when I wrote the play.

Why did you move there?

I’m an actor and that’s where the money is. But I had to come back for family reasons a few years ago. Now I’m married and live on the North Side.

When you were writing Token, did you consciously say I want White people to hear this?

Yes. The original script was focused on White people completely, but I changed it because I had something to say to Black people, too, because I’ve had a lot of negative experiences as well with Black people. So I was like, wait, this story really isn’t only about White people.

White people work in micro-aggressions and Black people work in just plain old aggressions. We don’t try to make it nice; we just tell you to your face what we think of you. I’ve had a lot of that in my life, where Black people were like, you don’t know who you are, you ain’t shit.

For me, it’s always, no, I know who I am, but we don’t all have to be the same. I’m just as Black as you are, but we’re different people. It’s okay, it doesn’t make me any less Black.

People think that because you’re from Naperville?

Exactly. They assume that I’m not woke; they assume that I must be a darker skinned Becky. People have always assumed that about me. I’m often ostracized by other Black people because I’m not “Black enough.” So no matter where I go, I’m an outsider. I’m not fully immersed in Black culture; I’m not fully immersed in White culture, so I’m always sort of orbiting around these two dichotomies.

Do you feel like you’re a different kind of Black?

I don’t feel like I’m a different kind of Black, I don’t think I’m some sort of an anomaly, but I’m treated as if I am, if that makes sense. I’m very comfortable in my Blackness. I know I’m Black and I have no problem with my Blackness. But the problem is that people absolutely have an idea of what Black is – whether they’re Black or not Black.

There’s a part in the show where you sort of indicate that if you’re the only Black person in the group – the token – you’re the authority on all things Black.

Yes, you have all the answers for the millions of Black people on the entire planet…because Black people all think the same apparently; we’re of like mind. That’s one of the most irritating things to me is that people assume that Black people are all the same; that we all think the same; that we all do the same things. So if I ask you a question as a Black person, you’re answering for the whole race.

If a White person was in a room with all Black people, they would notice that and go, hmmh.

I genuinely feel like it is a burden to have to be a part of a group. For instance, White people don’t always associate with, like, “We’re part of the White community.” That’s not a thing for a lot of them, unless they are the racists, they are not thinking of themselves as a group. They’re thinking, “I am an individual, I happen to be White, I do whatever I want. It has no reflection on my group.”

I don’t think most of them are actually aware that they are actively working as a group. Whereas, Black people are always aware that we are part of this group, we represent it, always. I think that’s kind of a burden, to always have to think that way.

What’s been the response to the show and now that you’ve done it, has it been cathartic?

I’m not getting any therapy from it. I didn’t write it for catharsis, I just wrote it because I thought these stories were relatable, so I wanted to share, like, hey this happened to me, didn’t it happen to you, too, haha, let’s talk about it.

I don’t feel better because I got it off my chest because that wasn’t the purpose in writing it. I feel good that people are coming up to me after the show and saying, “Oh, I know exactly what you’re talking about; that happened to me, too.” All people.

White people say, which has been really humbling, that, “Wow, you made me think about it and I saw myself in these characters and I never thought, oh, maybe that sounded racist.”

I’ve had people say I was humbled by what you said. That response has been interesting. Some have said, “I was uncomfortable, but maybe I needed to be uncomfortable.”

I think White audiences get scared, like, “Am I allowed to laugh at that? Am I supposed to laugh at that?” The White response has actually been very good, though, and I’m happy about that.

I did have one negative experience where a group of friends of friends who are very White left as soon as the show was over, didn’t say hi, they just left. But they absolutely needed to hear it because they were all of the things I was talking about.

If you have children, what will you tell them about race and how to handle race?

I guess I’ll tell them what my parents told me. My dad always said, never forget you’re Black, and that people are going to try to limit you, but never allow anybody to limit you. You are God’s child and as a child of God, you are powerful and men can’t limit you. Don’t let men limit your blessings. Always know who you are and walk in life with that.

I guess I would tell my kids, you are Black, but that doesn’t matter, so don’t let the world tell you who you are, based on what race you are. Besides, society won’t let you forget that you’re Black, even if you wanted to. The reminder happens on a daily basis. As soon as you start to forget, somebody comes up with some Black joke, or I’m in a room and go, okay, I’m the only Black person here.

It’s funny, after a show, a White person asked me, “So, do you just think about race all the time? Are you obsessed with it?” No, I’m not, but no one can tell me they don’t notice when they’re in a room and they’re the only one.

If a White person was in a room with all Black people, they would notice that and go, hmmh, there are a lot of Black people in here. So it’s not that I’m thinking about race; these are just objective observations.

Ultimately in the show, it’s your late grandmother who binds all the observations together with a big dose of common sense. Talk about her.

My grandmother, Sister Rosie Lee Lindsay, was an amazing woman from Mississippi who was loved by everyone she met. She moved from Mississippi to Chicago in the late 1950s and called the South Side at 67th and Langley her home all the way until her passing almost exactly a year ago.

She was strong-willed and opinionated and she loved Jesus more than life itself. Her words of wisdom throughout my life will stay with me always; she had a special way of blending serious life lessons with humor.

I use her as the voice of reason in the show because that’s truly what she was to me in my life. She was a true inspiration to me, and both she and my mother taught me how to be a strong and proud Black woman no matter where I was or what situation I found myself in. She exemplified what it meant to be fearless in speaking your truth and it’s the greatest gift she gave me.