A prominent Chicago businessman and political operative who has been one of the Black community’s biggest givers through the years has turned 90 years old.

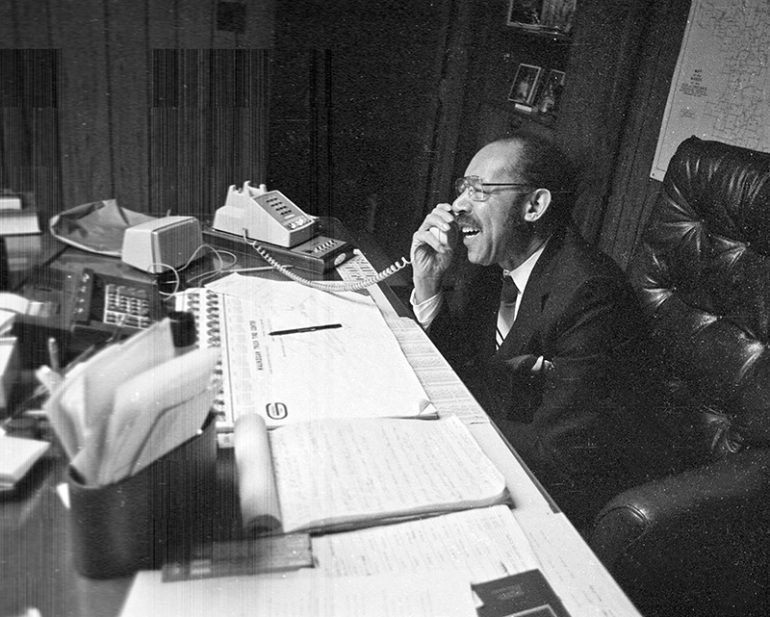

Howard Medley reached that landmark last week on March 19. Medley is founder of Medley’s Movers & Self Storage, located at 7001 South South Chicago Avenue.

In his heyday, Medley was one of the most important and powerful Black guys in Chicago’s Democratic machine. He raised vast amounts of money in campaign contributions and in return was rewarded with plenty of contracts.

Medley served as a cabinet member under five Chicago mayors and sat on numerous boards, including that of Seaway Bank.

Fresh From The Farm

He was born March 19, 1927, in Helena, Arkansas, the birthplace of his family friend, the late Cook County Board President John Stroger.

Medley lost his parents in 1930 at the age of three and he and his sister and brother were raised by their grandfather George Medley, along with his own seven children.

“My grandfather was a God fearing man who believed in and raised us by several scriptures in the Bible and I have been fortunate enough to raise my four children by those same principles,” Medley says.

“We were a farming family that believed in hard work and one example of my family’s dedication to excellence is that we won prizes for farming in Arkansas, Mississippi and Tennessee, as well as many other awards.”

Medley added, “This upbringing molded my later years and resulted in my office walls being lined with honors and awards from the many organizations I have served and supported.”

He was 16 when he moved from Helena to Chicago; then he was drafted into the military in 1945. It was toward the end of World War II, but serving in the Navy, Medley still managed to win a Purple Heart.

That honor is not something he pounds his chest over. “As far as the Purple Heart,” Medley says, “I don’t talk about that. I served my country with distinction, but that’s what I was sent to do. I’m proud of what I did and I did what I was told to do, like any other job I’ve had, that’s all. But I don’t dwell on that.”

Working Hard In Chicago

After being honorably discharged, he returned to Chicago, where he briefly attended junior college, but mostly worked for the post office for 14 years.

Married with a couple of kids, Medley felt the need for more income, so he worked a second job at night as a truck driver. By 1960, he had saved enough money to buy an apartment building.

Saving even more, he bought a second apartment building and with the rental money, bought a used truck for the necessity of hauling materials between the two units.

After neighbors steadily requested him to do light hauling jobs for them, Medley decided to hang out his shingle and go into the trucking, hauling and moving business. That’s how Medley Movers came about in 1964, operating out of office space on East 79th Street.

Business was good, his business grew and that’s when Medley became a community hero of sorts. He could always be counted on to make a community contribution financially.

The Bible says a good name is worth more than riches and gold. I want my family’s name back and I’ll fight until my last dying breath to clear it.

His largesse spread to sponsoring baseball, basketball and bowling teams and “I began to accept requests from schools, churches and community organizations to help them and their youth groups in their academic and athletic activities,” Medley says.

Over time, he became very popular, very wealthy and very giving. One of his favorite things to do was go down State Street in the summer time. “I’d see a bunch of kids around the ice cream guy and I’d tell the man to treat all of them. I just liked to do that,” Medley says.

“I like helping people less fortunate. I really believe this, so help me God I’m a high school dropout and if God put more bread on my table than I need, He must have intended for me to give it to somebody else.

“I had more money than I needed. I was getting money, getting contracts, so sure I liked helping people and I believe until this day that the reason I got the contracts I did is because of what I did in terms of helping people.”

Entrée Into Politics

As the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum in the 1960s and 70s, Medley was there for them, too. But he never took.

Rev. Willie Barrow of Operation PUSH once said, “You couldn’t give Medley nothing. He always said, ‘I don’t need PUSH, PUSH needs me.’ I remember once I couldn’t meet a payroll. I called Howard Medley. I said, Howard, ‘I need to have $10,000 to meet the payroll.’ Medley says, ‘You have it.'”

Medley laughs that eventually, politicians noticed that his little giving spigot was running full throttle. “It attracted the local politicians just running for office like aldermen,” Medley says.

“First they asked for a little donation, then because I had such a good name, they wanted to use my name on their literature as the chairman of their committees. I just went ahead and agreed and my name appeared as chairman of a lot of those committees even though I was nowhere around.”

After a community event where Medley as the emcee introduced then Mayor Richard J. Daley, the mayor beckoned him to his office for a talk.

“He told me he wanted me to join his cabinet because he needed a person like me. He wanted me on the Election Board,” Medley recalls. “I told him I was a high school dropout and didn’t think I was qualified.

“Well, the mayor got real upset and said, ‘Don’t ever say that. You pulled yourself up by your bootstraps; you’ve done so much. I’ll take my law degree off this wall and trade it for what you’ve done any day. People go to school to do this and that and you did it without that. Don’t tell nobody you’re not educated.’

“Well, I walked out of his office feeling 10-foot tall,” Medley says. And he accepted Daley’s job offer. As a Board of Election commissioner, Medley helped expand efforts to increase voter registration in the city, and he was a channel for Daley in the Black community.

A Succession Of Mayors

After Daley’s death, Medley remained on the Board of Elections until then Mayor Michael Bilandic caught hell in 1979 when CTA trains bypassed stations in Black areas during a monster snowstorm.

Medley says, “After that fiasco, Bilandic asked me to go over to the CTA and try to smooth out the problem. He said he thought I could help. I said okay, and went to the CTA board of commissioners, but it was too late. He still lost his election and Jane Byrne beat him.”

With a seven-year appointment as a CTA board commissioner, Medley became co-chairman of the Operations Committee and set out to help reform and improve daily operations.

After Mayor Jane Byrne was plagued with her own problems with the city’s police, she created the Chicago Police Brutality Committee and selected Medley to chair it, while simultaneously holding his post with the CTA.

Byrne’s problems swept her out of office, too, while a Black community groundswell swept Harold Washington into the mayoral seat in 1983. Medley was a confidant of Washington, who re-appointed him to a second seven-year term of the CTA board.

“What Harold Washington was doing was laying the groundwork for me to become Chairman of the CTA,” Medley claims. “That was the last big agency he was trying to get under his control. CTA had a billion dollar budget and 13,000 employees.

“Harold and I had lot of good talks about it and he wanted things to be done fairly over there at CTA,” Medley continued. “He made a point of saying he was the mayor of all Chicago, not the Black mayor. He wanted the jobs equalized, not all Black or white. He wanted them split up, and he told me, ‘I think you know what I mean.'”

A Career De-Railed

Then, at the age of 62 and at the height of his political and business career, Medley’s life went off the rails when shortly after Harold’s death in 1987, the feds indicted Medley for accepting a $25,000 bribe in his position as CTA commissioner under a complex real estate deal.

Medley said that an overzealous, vindictive federal prosecutor indicted him for what Medley characterizes as a “political vendetta.”

Medley says, “Working closely with Harold during the ‘Council Wars’ years until his untimely death made me a prime target for corrupt persons who resented some of the reforms implemented by our administration.

“In fact, the mayor informed me of information he had received that the U.S. Attorney was aggressively seeking grounds to charge me with official misconduct. On several occasions, the mayor urged me to watch my back.

“Of course, with his sudden death, being named chairman of the CTA board did not materialize for me and I became a victim of unscrupulous prosecutors who targeted and knowingly orchestrated an unjust indictment against me through the use of perjured grand jury testimony.”

Medley went to trial in November 1989 and ended up with a hung jury with an eight to four vote to acquit him. The prosecutors didn’t give up and in a second trial, Medley was convicted of bribery and sentenced to 30 months in prison. He served 10 months in a Duluth, Minnesota jail before being released.

After his release, Medley learned that the feds had wiretapped recordings of the man alleged to have bribed him. The tapes not only clear Medley of the accusations, but Medley says it means he never should have been indicted in the first place.

“Exonerating evidence was withheld during my trial, and in short, I was set up and convicted on bogus charges,” Medley says. “Thus began over two decades of hurt, harm and injury from which I have never recovered.”

All these years later, “I continue to suffer repercussions in business and my personal life,” Medley says. “My company is struggling to remain viable because I continue to be plagued by the label ‘convicted felon.’

“Before my wrongful conviction, I was a well-known philanthropist and advocate for the hopeless and voiceless, but now my participation and involvement in community, civic and church affairs have been severely limited due to this unjust and wrongful conviction.”

As a convicted felon, Medley can no longer serve on the board of his bank, as a financial trustee of his church, or participate on various other boards.

Ever since Medley was released from prison, he has been on a mission to clear his name, especially on the basis of the taped evidence that would clear him. Because he has served his time, the courts will not grant him a new trial.

Fighting For His Name

Medley has written and told his story to any number of media outlets, to 18 Illinois congressmen, two Illinois state senators, U.S. Senator Barack Obama, Attorney General Eric Holder, and Presidents George W. Bush and Donald Trump and he says he has spent over $1 million in the effort to get his name back.

“So why would I need a $25,000 bribe?” Medley says. “People who know me know that doesn’t make sense. That’s insulting. I never accepted perks that come with being a CTA commissioner. I paid the monthly lease myself for the city car we get. I paid the bill myself for the phones given to me at the CTA. I did that because I didn’t want to use the taxpayers’ money. I have my own money.”

Medley’s attorney in his first trial, James Montgomery, wrote to President Bush, “There is no question about Medley’s innocence. The courts have closed the door to his presenting evidence that would clearly vindicate him. “It is my considered judgment that Medley’s indictment and conviction was a deliberately contrived miscarriage of justice perpetrated by the government. I further believe that given access to the courts, Medley would be exonerated.”

Medley says he had never been arrested before in his life, that his grandfather raised all those kids that have never seen a jail, that he himself raised four kids that have never even gotten a traffic ticket that he knows about.

“We just didn’t live that kind of life, see,” he laments. “My grandfather used to say if you have not done anything wrong, you have nothing to worry about. I guess he did not know how low people will go and I was shocked because I never thought I’d be unfortunate enough to run into those kinds of unscrupulous people.”

Medley vows to spend all the time he has left and what money he has left to fight for his name as far as it goes, up to the Supreme Court, if necessary.

He says, “I’d like for a jury to listen to the tapes, listen to the arguments and tell me any one little thing that I did wrong and if they can find anything, anything, I’ll volunteer to go back to prison.

“The Bible says a good name is worth more than riches and gold. I want my family’s name back and I’ll fight until my last dying breath to clear it. There’s nothing more important to me than that.”

By David Smallwood, Chinta Strausberg and Melody McDowell

We love you. Uncle !