The 5th Annual Chicago Blues Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony will be held at Buddy Guy’s Legends club this Sunday, October 15, beginning at 2 p.m. Legends is located at 700 South Wabash. Tickets are $20 and attendees must be 21 and over to enter.

This year’s celebration will be dedicated to Legends’ longtime host, Michael Packer, who passed away earlier in 2017. This year’s ceremony is aptly titled “Michael Packer presents The Chicago Blues Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony.” Hosting the even will be Chicago media personality Jeanne Sparrow and performing will be the Mike Wheeler Band.

A special feature of this year’s ceremony is the induction of the Pioneer Blues Legends. Those inductees are the legendary Pervis Spann, The Blues Man, and Herman Roberts, proprietor of Roberts Motel and Roberts Showclub.

A special award will go to Melody Spann-Cooper and radio station WVON, with the presentation of the annual Legend Award going to Little Walter.

The Induction Ceremony will also recognize the historic Chicago blues clubs and their owners of the West and South sides, including Clarence Ludd of the High Chaparral; Artis Ludd (posthumously) of Artis’ Lounge; Don and Larry Simmons of The Taste; Artie “Blues Boy” White (posthumously) of Bootsie’s; Mozell Barnes of East of The Ryan and Mr. G’s; Larry Stevens of Larry’s; Hayes Harris of the Good Rockin’ Horse; and Willie Moore of Lump’s Showcase.

Blues Legend Awards will be presented to Eddie C. Campbell, Holle Thee Maxwell, Gene “Daddy G” Barge, John Primer, Carl Weathersby, and Big Llou Johnson (the voice of Bluesville radio and blues artist).

Blues Master Awards will be presented to: Katherine Davis, Benny Turner, Abb Locke (sax), Mary Lane, Zora Young, Shirley Johnson, Smiley Tillmon, Little Ed & The Blues Imperials, Big James Montgomery, Felton Crews (famous bass player), Ariyo (current piano, Sons of Blues, past, Otis Rush & more), Mose Rutues (Sons of Blues, Retired), Vance Kelly, Carlos Johnson, Kenny Kinsey & Ralph Kinsey, Maurice John Vaughn, Quintus McCormick, Sugar Blue, Little Al Thomas, Pierre Lacocque & Mississippi Heat, Peaches Staten, Eddie Taylor, Jr., Erwin Helsfer, and Barry Goldberg.

Blues has its cycle, it has its spot, it will come back. It’ll just take a minute or so.

Blues In The Hood

These days Chicago blues is part of the local tourism, with an annual outdoor festival devoted to the music, but there was a time, from the 1970s on back, when the blues was viewed as the poor relation of jazz.

While jazz was just polished enough to be heard and seen in upscale venues north of Roosevelt Road, blues was confined to taverns and show lounges on the South and West sides.

Maybe on occasion you might be lucky to see blues artists in large theaters like the Regal on 47th and South Park (now a carpark at 47th and King Drive), but the music was by and large almost underground.

When the Rolling Stones first came to Chicago around 1965, Mick Jagger told a local reporter at one of the dailies that the band wished to see Muddy Waters, the blues legend. The out-of-touch reporter wondered exactly where these “muddy waters” were the Stones wanted to look at.

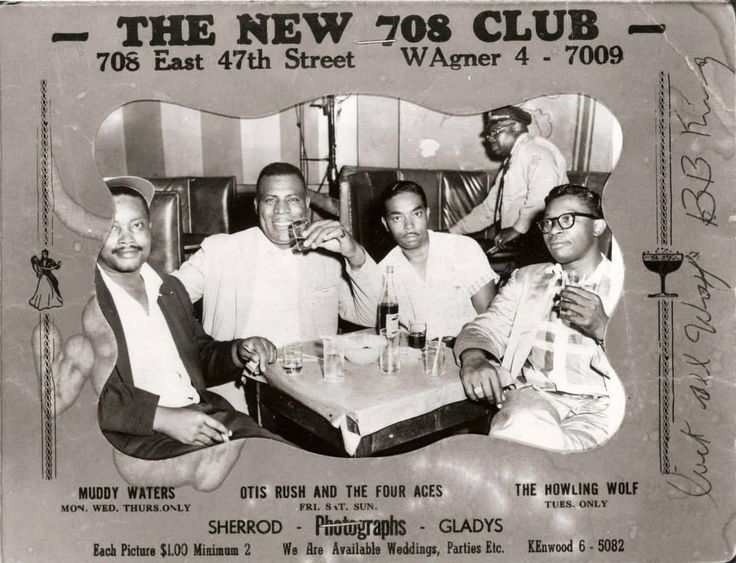

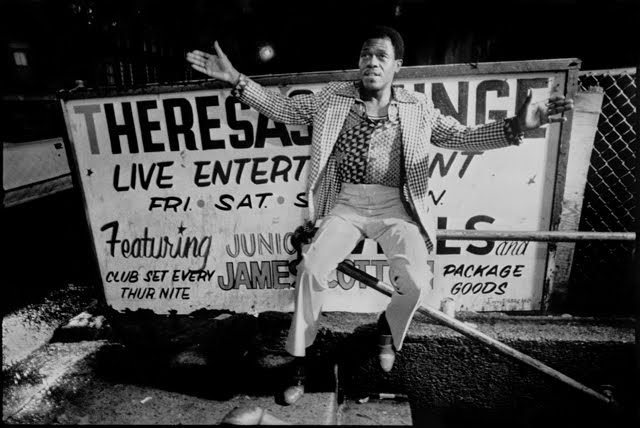

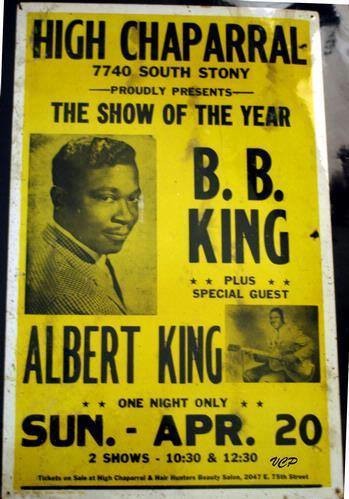

Good question. These “muddy waters,” along with other similar artists, could be found at Theresa’s, the 1815 Club, the Burning Spear, Turner’s, the High Chaparral, the I Spy, Queen Bee’s (later re-birthed in the ‘80s as Lee’s Unleaded Blues), the Castle Rock, Big Bill’s Copacabana, the Zanzibar. These may have been mere watering holes to the uninitiated, but they were as important to the local lore as any club on the Rush Street strip.

After a transitional phase in the 1970s, awareness of Chicago blues roared into the ‘80s with guns blazing. The North Side, once a blues-resistant area, became a hotbed for the music. If someone from out of town asked where blues could be heard, you could rattle off a whole litany of places: Kingston Mines. Rosa’s. B.L.U.E.S. (and its sister venue, B.L.U.E.S. Etc.). Wise Fools Pub. Buddy Guy’s Legends. With a couple of exceptions, most are still around.

While it was good to see that blues was being recognized across the city, it should be noted that blues in Black neighborhoods didn’t die. Even during the historic era when “house” music was being invented, you could still drop by the Checkerboard Lounge on 47th Street, which until 1989 was co-owned by singer/guitarist Buddy Guy.

The East of the Ryan on 79th Street hosted the historic likes of Tyrone Davis, Bobby Bland, Clarence Carter and other greats in the field. Lee’s Unleaded Blues presented this music seven nights a week for those needing more than a weekly fix. Rolling into the 90s and Y2K, you could see Billy Branch & the Sons of the Blues holding down the fort on Monday nights at Artis’s on 87th.

Out west on North Avenue, Tail Dragger would act a fool at the 5105 Club on Sundays. Even as late as the 2000s, on Madison Street, when the Five Aces Social Club closed down, a restaurant called Wallace’s Catfish Corner started featuring live blues on the weekends in their parking lot. Singer/harmonicist Cyrus Hayes plus his band and assorted guests set up on a flatbed truck and partied the night away. During the summers, after the Chicago Blues Festival, this was a good shot of the real before the night was over.

One such neighborhood club was the now-defunct Bootsy’s. Established by the late blues singer Artie “Blues Boy” White, it was originally located at 23rd and Cottage Grove in 1977 before relocating to 55th and State in 1984. Compared to The Taste, Bootsy’s was a smaller club with a more intimate atmosphere.

According to Joseph White, Artie’s son, “it was a place where blues singers could showcase their talent. It was like a blues singer’s Cheers,” referring to the famed TV sitcom about a Boston bar “where everybody knows your name.”

Indeed, everybody knew the names of Bobby Rush, Tyrone Davis, Otis Clay, Little Milton, Garland Green, Alvin Cash and Lou Rawls. White says that all of these men would occasionally sit in with the house band, normally led by Ronnie Hicks, Rico McFarland, Dave Parker or Scotty & the Rib Tips.

A few local comedians would stop by, too, including Hi-Fi White, Manuel Arrington, and even Rudy Ray Moore, who tried to recruit Artie White for his 1977 movie, Petey Wheatstraw, The Devil’s Son-In-Law. White refused – his son says that he didn’t want to do any karate moves in the picture – so Alvin Cash took his place.

This kind of camaraderie was not unexpected in South and West Side clubs. Says Joseph White: “I stress this – my father was instrumental for launching a lot of blues musicians who played with B.B. King, Albert King. It was like a showcase.”

Bettie Payton-White, the widow of the owner, adds, “We’re carrying on his legacy with the Artie White Youth Scholarship Foundation.” The first recipient was a teenaged blues guitarist named Christone “Kingfish” Ingram.

In recent years, this seems to have come to an end. Artis’s and Lee’s Unleaded Blues probably did more than anyone to keep South Side blues in circulation. Both clubs quietly ground to a halt, with little fanfare. The fabled Checkerboard Lounge moved to a larger, classier spot in Hyde Park’s Harper Court in 2005; declining attendance, coupled with owner L.C. Thurman’s death, caused it to close in 2015. Just last year, the B&B opened on 4422 W. Madison, but that too has seemed to fade into oblivion.

Taste Of The Taste

Still, other survivors exist on the landscape. Larry and Donald Simmons founded the Taste Entertainment Center in 1980. Located in the Englewood neighborhood, the fact that it was established at all is almost as remarkable as the fact that it survived.

As Donald Simmons recollects, “We opened July 30, 1980. Things were okay. There weren’t that great, but okay. We started off trying to bring something for the community.” Due to Englewood’s negative reputation as a less-than-savory area, “we were denied for a loan by the big banks. But Stu Collins at Seaway National Bank gave us a loan,” Simmons says.

Emphasizing the community role, Simmons continued, “Everybody that was connected with the club was Black. The architects were Black. The construction guys who built the building were Black. There were all types of things to deny us, but we stayed focused. The club was built for what we were doing. Very state of the art at that particular time.”

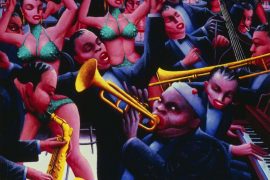

Hitting the ground running, Taste presented a dizzying array of blues and jazz talent playing in their Zodiac Room: Billy Branch, Lefty Dizz, J.W. Williams, Buddy Guy, Tyrone Davis, Jimmy McGriff, David “Fathead” Newman, Dakota Staton and others. George Benson, the Commodores, Tupac Shakur, Rick James, the Isley Brothers and “all the Jacksons except Michael” dropped by just to hang out. They even had their own showgirls, one of whom was future actress Lisa Raye.

Simmons reflects, “We were the number one thing in town – waterfalls, exotic fish in tanks, we had the video system set up so you could see what was going on in the Zodiac Room from the bar. That went on for 15 years.”

Why did this heyday end? Simmons credits the rap/hip-hop explosion. “Rap didn’t phase us out,” Simmons says. “It just changed the demographics of the club. It was a process, and the audience got younger.” Despite the changeover, the club still thrives with the likes of Vance Kelly playing regularly.

Asked why blues doesn’t seem to be as prevalent in blues clubs as it used to be, Joseph White blames the radio stations. “Used to be a time when the disc jockeys would play what people wanted to hear. After rap came in, the stations put blues on the back burner,” White says.

Simmons is a little more critical: “We don’t support our own venues. The blues clubs up north stole all our clientele. We’ll go to the North Side and spend our paycheck for the next week and then come back to the South Side begging,” he laments. “For some reason, if you have a cover charge on the South Side, they don’t want to come in and pay it. If you have a drink minimum, they don’t want that.

“Whites will come south, but as far as Blacks, we don’t support our own venues. The new millennials will support Hyde Park and the south Loop, but not the South Side. We don’t get the respect.”

While the blues aren’t exactly red hot in the hood at present, Simmons foresees a turnaround. “It’s a process…it wont happen tomorrow or next year, but it will turn itself around. It’s like a revolving wheel. It has its cycle, it has its spot, it will come back. It’ll just take a minute or so.”

(This article was written by James Porter.)